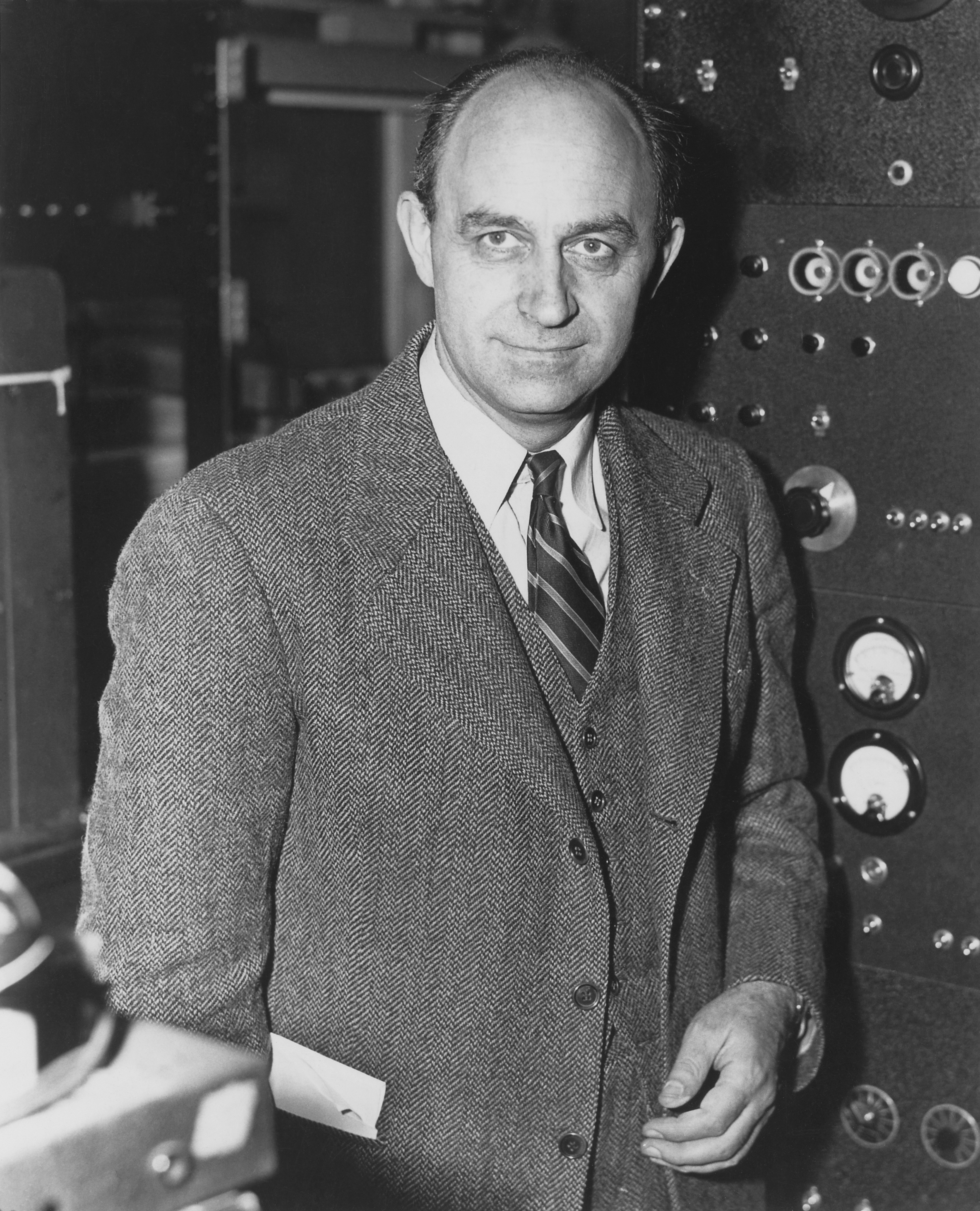

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (Italian: [enˈriːko ˈfermi]; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and later naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age"[1] and the "architect of the atomic bomb".[2] He was one of very few physicists to excel in both theoretical physics and experimental physics. Fermi was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on induced radioactivity by neutron bombardment and for the discovery of transuranium elements. With his colleagues, Fermi filed several patents related to the use of nuclear power, all of which were taken over by the US government. He made significant contributions to the development of statistical mechanics, quantum theory, and nuclear and particle physics.

"Fermi" redirects here. For other uses, see Fermi (disambiguation).

Enrico Fermi

29 September 1901

28 November 1954 (aged 53)

- Italy (1901–1944)

- United States (1944–1954)

2

- Matteucci Medal (1926)

- Nobel Prize (1938)

- Hughes Medal (1942)

- Medal for Merit (1946)

- Franklin Medal (1947)

- ForMemRS (1950)

- Barnard Medal for Meritorious Service to Science (1950)

- Rumford Prize (1953)

- Max Planck Medal (1954)

Fermi's first major contribution involved the field of statistical mechanics. After Wolfgang Pauli formulated his exclusion principle in 1925, Fermi followed with a paper in which he applied the principle to an ideal gas, employing a statistical formulation now known as Fermi–Dirac statistics. Today, particles that obey the exclusion principle are called "fermions". Pauli later postulated the existence of an uncharged invisible particle emitted along with an electron during beta decay, to satisfy the law of conservation of energy. Fermi took up this idea, developing a model that incorporated the postulated particle, which he named the "neutrino". His theory, later referred to as Fermi's interaction and now called weak interaction, described one of the four fundamental interactions in nature. Through experiments inducing radioactivity with the recently discovered neutron, Fermi discovered that slow neutrons were more easily captured by atomic nuclei than fast ones, and he developed the Fermi age equation to describe this. After bombarding thorium and uranium with slow neutrons, he concluded that he had created new elements. Although he was awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery, the new elements were later revealed to be nuclear fission products.

Fermi left Italy in 1938 to escape new Italian racial laws that affected his Jewish wife, Laura Capon. He emigrated to the United States, where he worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Fermi led the team at the University of Chicago that designed and built Chicago Pile-1, which went critical on 2 December 1942, demonstrating the first human-created, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. He was on hand when the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge, Tennessee went critical in 1943, and when the B Reactor at the Hanford Site did so the next year. At Los Alamos, he headed F Division, part of which worked on Edward Teller's thermonuclear "Super" bomb. He was present at the Trinity test on 16 July 1945, the first test of a full nuclear bomb explosion, where he used his Fermi method to estimate the bomb's yield.

After the war, he helped establish the Institute for Nuclear Studies at Chicago, and served on the General Advisory Committee, chaired by J. Robert Oppenheimer, which advised the Atomic Energy Commission on nuclear matters. After the detonation of the first Soviet fission bomb in August 1949, he strongly opposed the development of a hydrogen bomb on both moral and technical grounds. He was among the scientists who testified on Oppenheimer's behalf at the 1954 hearing that resulted in the denial of Oppenheimer's security clearance.

Fermi did important work in particle physics, especially related to pions and muons, and he speculated that cosmic rays arose when material was accelerated by magnetic fields in interstellar space. Many awards, concepts, and institutions are named after Fermi, including the Fermi 1 (breeder reactor), the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station, the Enrico Fermi Award, the Enrico Fermi Institute, the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, the Fermi paradox, and the synthetic element fermium, making him one of 16 scientists who have elements named after them.

Death[edit]

Fermi underwent what was called an "exploratory" operation in Billings Memorial Hospital in October 1954, after which he returned home. Fifty days later he died of inoperable stomach cancer in his home in Chicago. He was 53.[2] Fermi suspected working near the nuclear pile involved great risk but he pressed on because he felt the benefits outweighed the risks to his personal safety. Two of his graduate student assistants working near the pile also died of cancer.[134]

A memorial service was held at the University of Chicago chapel, where colleagues Samuel K. Allison, Emilio Segrè, and Herbert L. Anderson spoke to mourn the loss of one of the world's "most brilliant and productive physicists."[135] His body was interred at Oak Woods Cemetery where a private graveside service for the immediate family took place presided by a Lutheran chaplain.[136]

Impact and legacy[edit]

Legacy[edit]

Fermi received numerous awards in recognition of his achievements, including the Matteucci Medal in 1926, the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1938, the Hughes Medal in 1942, the Franklin Medal in 1947, and the Rumford Prize in 1953. He was awarded the Medal for Merit in 1946 for his contribution to the Manhattan Project.[137] Fermi was elected member of the American Philosophical Society in 1939 and a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1950.[138][139] The Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence, known as the Temple of Italian Glories for its many graves of artists, scientists and prominent figures in Italian history, has a plaque commemorating Fermi.[140] In 1999, Time named Fermi on its list of the top 100 persons of the twentieth century.[141] Fermi was widely regarded as an unusual case of a 20th-century physicist who excelled both theoretically and experimentally. Chemist and novelist C. P. Snow wrote, "if Fermi had been born a few years earlier, one could well imagine him discovering Rutherford's atomic nucleus, and then developing Bohr's theory of the hydrogen atom. If this sounds like hyperbole, anything about Fermi is likely to sound like hyperbole".[142]

Fermi was known as an inspiring teacher and was noted for his attention to detail, simplicity, and careful preparation of his lectures.[143] Later, his lecture notes were transcribed into books.[144] His papers and notebooks are today in the University of Chicago.[145] Victor Weisskopf noted how Fermi "always managed to find the simplest and most direct approach, with the minimum of complication and sophistication."[146] He disliked complicated theories, and while he had great mathematical ability, he would never use it when the job could be done much more simply. He was famous for getting quick and accurate answers to problems that would stump other people. Later on, his method of getting approximate and quick answers through back-of-the-envelope calculations became informally known as the "Fermi method", and is widely taught.[147]

Fermi was fond of pointing out that when Alessandro Volta was working in his laboratory, Volta had no idea where the study of electricity would lead.[148] Fermi is generally remembered for his work on nuclear power and nuclear weapons, especially the creation of the first nuclear reactor, and the development of the first atomic and hydrogen bombs. His scientific work has stood the test of time. This includes his theory of beta decay, his work with non-linear systems, his discovery of the effects of slow neutrons, his study of pion-nucleon collisions, and his Fermi–Dirac statistics. His speculation that a pion was not a fundamental particle pointed the way towards the study of quarks and leptons.[149]

For a full list of his papers, see pages 75–78 in ref.[139]