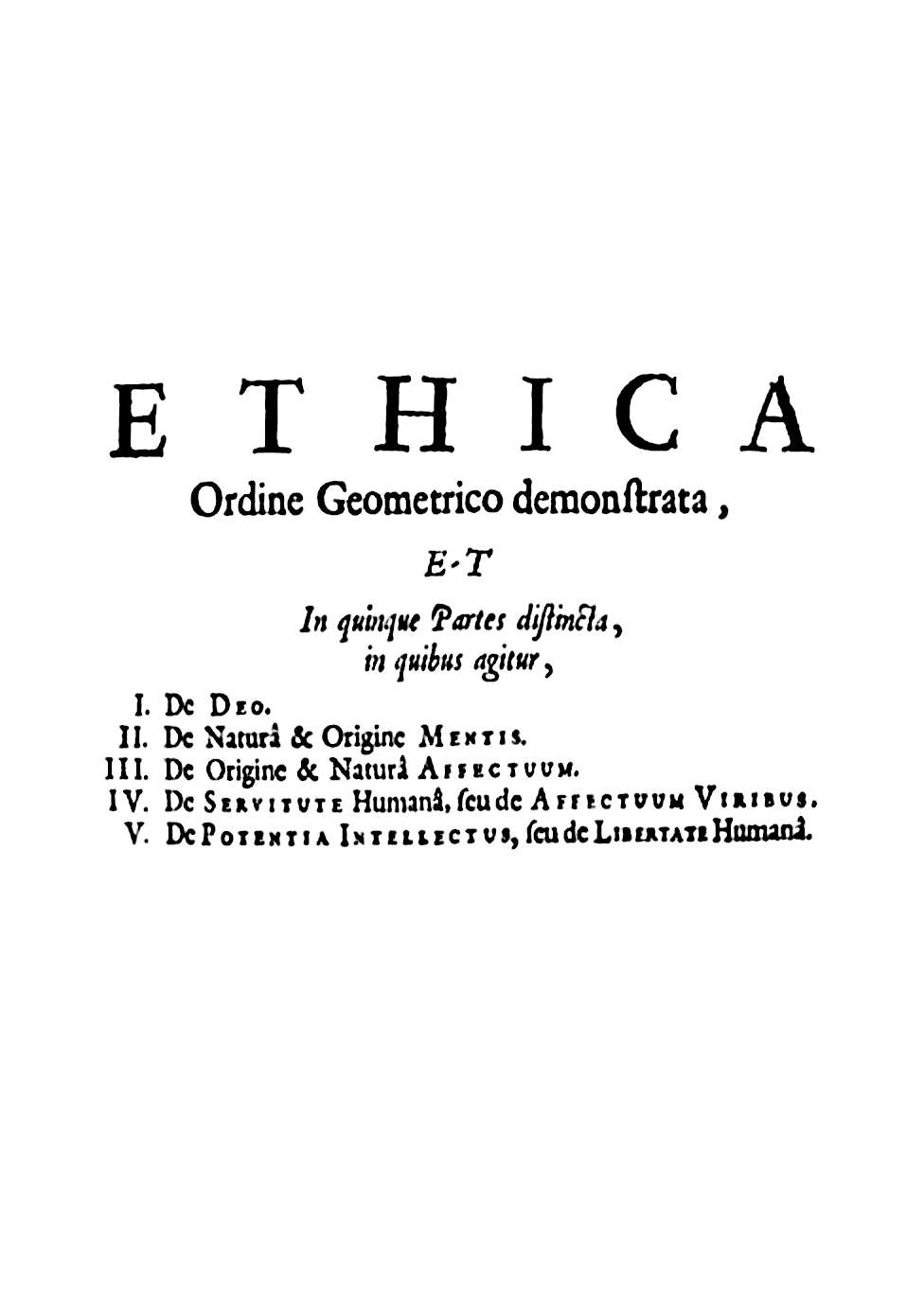

Ethics (Spinoza book)

Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order (Latin: Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata), usually known as the Ethics, is a philosophical treatise written in Latin by Baruch Spinoza (Benedictus de Spinoza). It was written between 1661 and 1675[1] and was first published posthumously in 1677.

Author

The book is perhaps the most ambitious attempt to apply Euclid's method in philosophy. Spinoza puts forward a small number of definitions and axioms from which he attempts to derive hundreds of propositions and corollaries, such as "When the Mind imagines its own lack of power, it is saddened by it",[2] "A free man thinks of nothing less than of death",[3] and "The human Mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the Body, but something of it remains which is eternal."[4]

Themes[edit]

God or Nature[edit]

According to Spinoza, God is Nature and Nature is God (Deus sive Natura). This is his pantheism. In his previous book, Theologico-Political Treatise, Spinoza discussed the inconsistencies that result when God is assumed to have human characteristics. In the third chapter of that book, he stated that the word "God" means the same as the word "Nature". He wrote: "Whether we say ... that all things happen according to the laws of nature, or are ordered by the decree and direction of God, we say the same thing." He later qualified this statement in his letter to Oldenburg[12] by abjuring materialism.[13] Nature, to Spinoza, is a metaphysical substance, not physical matter.[14] In this posthumously published book Ethics, he equated God with nature by writing "God or Nature" four times.[15] "For Spinoza, God or Nature—being one and the same thing—is the whole, infinite, eternal, necessarily existing, active system of the universe within which absolutely everything exists. This is the fundamental principle of the Ethics...."[16]

Spinoza holds that everything that exists is part of nature, and everything in nature follows the same basic laws. In this perspective, human beings are part of nature, and hence they can be explained and understood in the same way as everything else in nature. This aspect of Spinoza's philosophy — his naturalism — was radical for its time, and perhaps even for today. In the preface to Part III of Ethics (relating to emotions), he writes:

Criticism[edit]

Number of attributes[edit]

Spinoza's contemporary, Simon de Vries, raised the objection that Spinoza fails to prove that substances may possess multiple attributes, but that if substances have only a single attribute, "where there are two different attributes, there are also different substances".[31] This is a serious weakness in Spinoza's logic, which has yet to be conclusively resolved. Some have attempted to resolve this conflict, such as Linda Trompetter, who writes that "attributes are singly essential properties, which together constitute the one essence of a substance",[32] but this interpretation is not universal, and Spinoza did not clarify the issue in his response to de Vries.[33] On the other hand, Stanley Martens states that "an attribute of a substance is that substance; it is that substance insofar as it has a certain nature"[34] in an analysis of Spinoza's ideas of attributes.

Misuse of words[edit]

Schopenhauer claimed that Spinoza misused words. "Thus he calls 'God' that which is everywhere called 'the world'; 'justice' that which is everywhere called 'power'; and 'will' that which is everywhere called 'judgement'."[35] Also, "that concept of substance...with the definition of which Spinoza accordingly begins...appears on close and honest investigation to be a higher yet unjustified abstraction of the concept matter."[36]