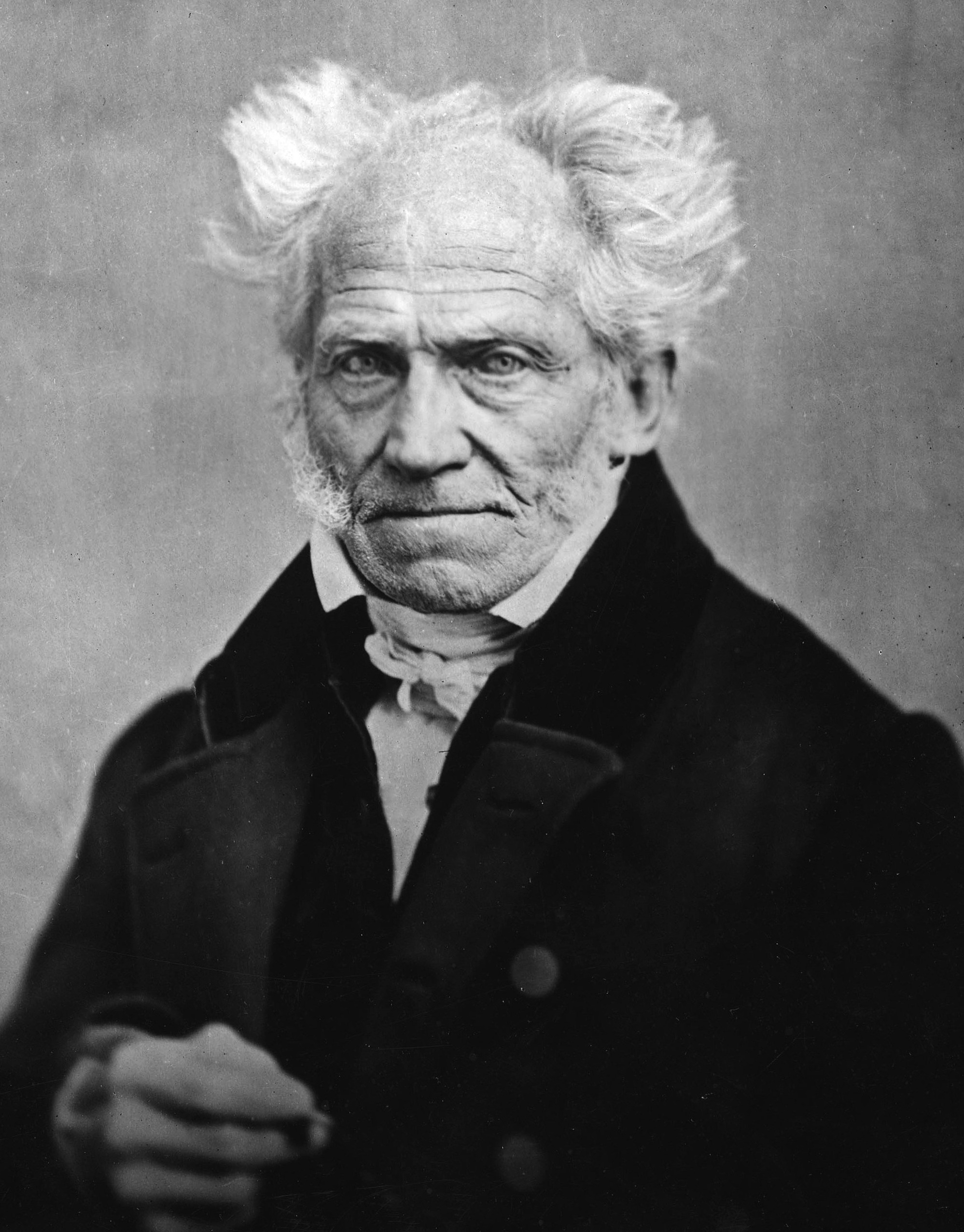

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer (/ˈʃoʊpənhaʊər/ SHOH-pən-how-ər,[9] German: [ˈaʁtuːɐ̯ ˈʃoːpn̩haʊɐ] ⓘ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manifestation of a blind and irrational noumenal will.[10][11][12] Building on the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Schopenhauer developed an atheistic metaphysical and ethical system that rejected the contemporaneous ideas of German idealism.[7][8]

"Schopenhauer" redirects here. For other uses, see Schopenhauer (disambiguation).

Arthur Schopenhauer

22 February 1788

21 September 1860 (aged 72)

German

- Johanna Schopenhauer (mother)

- Adele Schopenhauer (sister)

Metaphysics, aesthetics, ethics, morality, psychology

- Anthropic principle[4][5]

- Eternal justice

- Fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason

- Hedgehog's dilemma

- Philosophical pessimism

- Principium individuationis

- Will as thing in itself

- Animal ethics[6]

- Criticism of religion

- Criticism of German idealism[7][8]

- Schopenhauerian aesthetics

- Wooden iron

Schopenhauer was among the first thinkers in Western philosophy to share and affirm significant tenets of Indian philosophy, such as asceticism, denial of the self, and the notion of the world-as-appearance.[13] His work has been described as an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism.[14] Though his work failed to garner substantial attention during his lifetime, he had a posthumous impact across various disciplines, including philosophy, literature, and science. His writing on aesthetics, morality, and psychology have influenced many thinkers and artists.

Philosophy[edit]

Theory of perception[edit]

In November 1813 Goethe invited Schopenhauer to help him on his Theory of Colours. Although Schopenhauer considered colour theory a minor matter,[37] he accepted the invitation out of admiration for Goethe. Nevertheless, these investigations led him to his most important discovery in epistemology: finding a demonstration for the a priori nature of causality.

Kant openly admitted that it was Hume's skeptical assault on causality that motivated the critical investigations in Critique of Pure Reason and gave an elaborate proof to show that causality is a priori. After G. E. Schulze had made it plausible that Kant had not disproven Hume's skepticism, it was up to those loyal to Kant's project to prove this important matter.

The difference between the approaches of Kant and Schopenhauer was this: Kant simply declared that the empirical content of perception is "given" to us from outside, an expression with which Schopenhauer often expressed his dissatisfaction.[38] He, on the other hand, was occupied with the questions: how do we get this empirical content of perception; how is it possible to comprehend subjective sensations "limited to my skin" as the objective perception of things that lie "outside" of me?[39]

Thoughts on other philosophers[edit]

Giordano Bruno and Spinoza[edit]

Schopenhauer saw Bruno and Spinoza as philosophers not bound to their age or nation. "Both were fulfilled by the thought, that as manifold the appearances of the world may be, it is still one being, that appears in all of them. ... Consequently, there is no place for God as creator of the world in their philosophy, but God is the world itself."[125][126]

Schopenhauer expressed regret that Spinoza stuck, for the presentation of his philosophy, with the concepts of scholasticism and Cartesian philosophy, and tried to use geometrical proofs that do not hold because of vague and overly broad definitions. Bruno on the other hand, who knew much about nature and ancient literature, presented his ideas with Italian vividness, and is amongst philosophers the only one who comes near Plato's poetic and dramatic power of exposition.[125][126]

Schopenhauer noted that their philosophies do not provide any ethics, and it is therefore very remarkable that Spinoza called his main work Ethics. In fact, it could be considered complete from the standpoint of life-affirmation, if one completely ignores morality and self-denial.[127] It is yet even more remarkable that Schopenhauer mentions Spinoza as an example of the denial of the will, if one uses the French biography by Jean Maximilien Lucas[128] as the key to Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione.[129]