Ethics in the Bible

Ethics in the Bible refers to the system(s) or theory(ies) produced by the study, interpretation, and evaluation of biblical morals (including the moral code, standards, principles, behaviors, conscience, values, rules of conduct, or beliefs concerned with good and evil and right and wrong), that are found in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. It comprises a narrow part of the larger fields of Jewish and Christian ethics, which are themselves parts of the larger field of philosophical ethics. Ethics in the Bible is unlike other western ethical theories in that it is seldom overtly philosophical. It presents neither a systematic nor a formal deductive ethical argument. Instead, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character in what is sometimes referred to as virtue ethics. This moral reasoning is part of a broad, normative covenantal tradition where duty and virtue are inextricably tied together in a mutually reinforcing manner.

Some critics have viewed certain biblical teachings to be morally problematic and accused it of advocating for slavery, genocide, supersessionism, the death penalty, violence, patriarchy, sexual intolerance and colonialism. The problem of evil, an argument that is used to argue against the existence of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic God, is an example of criticism of ethics in the Bible.

Conversely, it has been seen as a cornerstone of both Western culture, and many other cultures across the globe. Concepts such as justice for the widow, orphan and stranger provided inspiration for movements ranging from abolitionism in the 18th and 19th century, to the civil rights movement, the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and liberation theology in Latin America.

Overview[edit]

The Bible[edit]

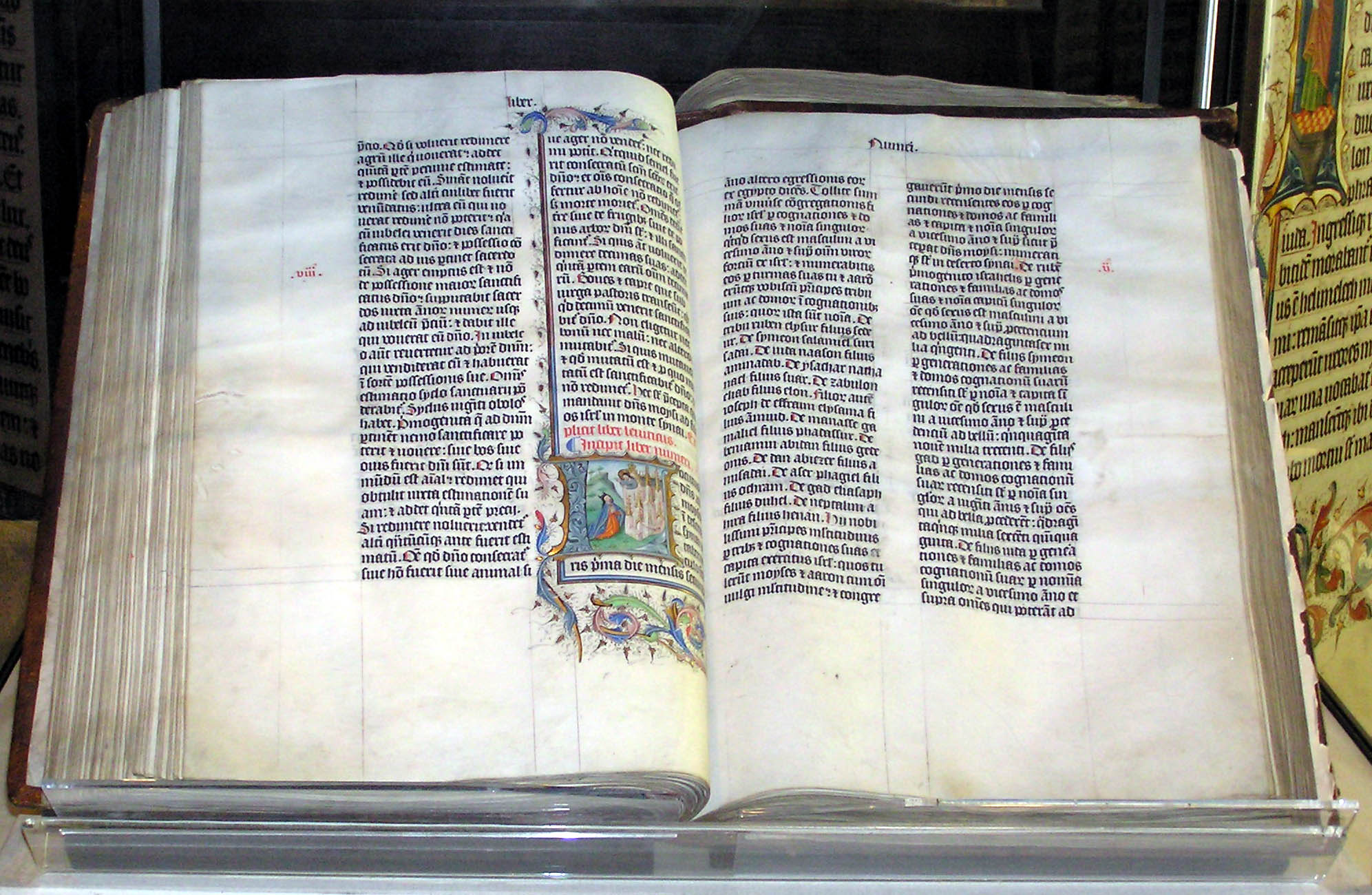

According to traditional Jewish enumeration, the Hebrew Bible is composed of 24 books which came into being over a span of almost a millennium.[1]: 17 The Bible's earliest texts reflect a Late Bronze Age civilization of the Ancient Near East, while its last text, usually thought to be the Book of Daniel, comes from a second century BCE Hellenistic period. This historical development has to be taken into consideration in any account of ethics in the Bible.[1]: 17 Ethicist Eryl W. Davies writes that many scholars question whether the biblical account can be regarded as an accurate account of "how it really happened." The Bible has an "air of appearing to know things we are actually very unsure about, and it has tended to state as fact what was merely speculation... There is a growing recognition it reflects the ethical values and norms of the educated class in ancient Israel, and that very little can be known about the moral beliefs of the 'ordinary' Israelites."[2]: 111 As a result, many scholars believe the Bible is unsuitable for "doing philosophy."[3]: 148 Philosopher Jaco Gericke quotes philosopher Robert P. Carroll saying the Bible is "too untidy, too sprawling, and too boisterous to be tamed by neat systems of thought."[3]: 148

At the same time, ethicist John Barton says most scholars recognize the Bible is "more than just a jumble of isolated precepts with no underlying rationale."[4]: 46 The biblical narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, parables, and unique genrés of the Bible are the sources of its ethical concepts.[1]: 1, 2 However, Barton also says there are problematic texts and the author's intent is not always easy to decipher. Much of biblical narrative refrains from direct comment, and there are problems in turning to the narratives for ethical insight.[5]: 1–3 "First... the narratives are often far from morally edifying... Second, though Old Testament stories are about what we might call 'moral issues', it is often not easy to decide what is being commended and what deplored. Third there is a general problem about describing the moral world of biblical narrative... are we talking about the real world...or the imagined world?"[5]: 3 [1]: 1–17 Barton concludes, the Bible's moral "philosophy is more complicated than it might appear."[5]: 9

Jewish philosophers Shalom Carmy and David Schatz explain one of many difficulties doing philosophy in the Bible is that philosophers dislike contradicting themselves whereas the Bible, by contrast, "often juxtaposes contradictory ideas, without explanation or apology".[6]: 13–14 Gericke says using a descriptive, rather than an analytical philosophical approach, means the pluralism of the Bible need not be a problem. Descriptive philosophy is aimed purely at clarifying meaning and therefore, it has no difficulty "simply stating the nature of the diachronic variation and synchronic variability found in the biblical texts."[3]: 146 Carmy and Schatz say the Bible does philosophical activity when it "depicts the character of God, presents an account of creation, posits a metaphysics of divine providence and divine intervention, suggests a basis for morality, discusses many features of human nature, and frequently poses the notorious conundrum of how God can allow evil."[6]: 13, 14

Ethics[edit]

Philosopher Alan Mittleman says ethics in the Bible is not like western ethical theories in that it is seldom overtly "philosophical." It presents neither a systematic nor a deductive formal ethical argument, nor does it address traditional Western philosophical questions and arguments.[1]: 1, 2 [7] The absence of Western approaches is not evidence there is an absence of ethics in the Bible however. Textual scholar Jaco Gericke writes, "The tendency to deny the Hebrew Bible anything philosophical when its rhetoric does not conform to Western varieties of philosophical systems actually involves a colonialist ethnocentric hermeneutical fallacy."[3]: 156–157 [3]: 156

While there is no Western-style ethical system in the Bible, there are folk philosophical presuppositions in it; "in other words, the biblical texts contain metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical assumptions about the nature of reality, existence, life, knowledge, truth, belief, good and evil, value and so on" of the ancient folk who recorded it.[3]: 157 Considering ethics in the Bible, therefore, means not using philosophical terms such as "deontological", "casuistic", "apodictic", and "theodicy", while still recognizing that, if a piece of literature contains ethical assumptions, it contains metaphysical and epistemological assumptions as well.[3]: 211 It is "impossible to understand the Bible's fundamental structures of meaning without attending to the text's basic assumptions regarding reality, knowledge and value."[3]: 9, 206 These assumptions fall into the four basic philosophical categories.[3]: 157

Ethical paradigms[edit]

Ethicist John Barton says there are three basic models, patterns or paradigms that form the basis of all ethics in the Bible: (1) obedience to God's will; (2) natural law; and (3) the imitation of God.[4]: 46–47 Barton goes on to say the first is probably the strongest model.[4]: 51 Obedience as a basis for ethics is found in Law and in the wisdom literature and in the Prophets. Eryl Davies says it is easy to overemphasize obedience as a paradigm since there is also a strong goal–oriented character to the moral teaching in the Bible.[2]: 112 Asking where a course of action would lead was normal for the culture portrayed in biblical texts, and even laws have "motive clauses" oriented toward the future prosperity of the person being asked to obey.[4]: 46–48, 52

"Natural law" as Barton uses it is "a vague phrase meant to be suggestive rather than defining."[4]: 48 Eryl Davies says it is a term that should be used with some reservation since this is not the highly developed "natural law" found in Western thought. Nevertheless, the loosely defined paradigm is suggested by the ordering of the book of Genesis, where the creation story and the natural order were made a focal point as the book was assembled and edited. Natural law is in the Wisdom literature, the Prophets, Romans 1, and Acts 17.[4]: 49 [4]: 48 Natural law can be found in the book of Amos, where nations other than Israel are held accountable for their ethical decisions (Amos 1:3–2:5) even though they don't know the Hebrew god.[4]: 50

Davies says the clearest expression of the imitation of God as a basis for ethics is in Leviticus 19:2 where Yahweh instructs Moses to tell the people to be holy because Yahweh is holy.[2]: 112 This idea is also in Leviticus 11:44; 20:7,26; 21:8. The prophets also asserted that God had moral qualities the Israelites should emulate. The Psalmists also frequently reflect on God's character forming the basis of the ethical life of those who worship Yahweh. Psalm 111, and 112 set out the attributes of God that must be reflected in the life of a 'true follower'.[2]: 112 The ethic has limits; Barton points out that in 1 Samuel 26:19 David argues that if his own persecution is ordered by God that is one thing, but if it is the work of people, those people should be cursed.[4]: 51