Bible

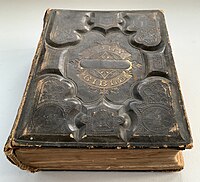

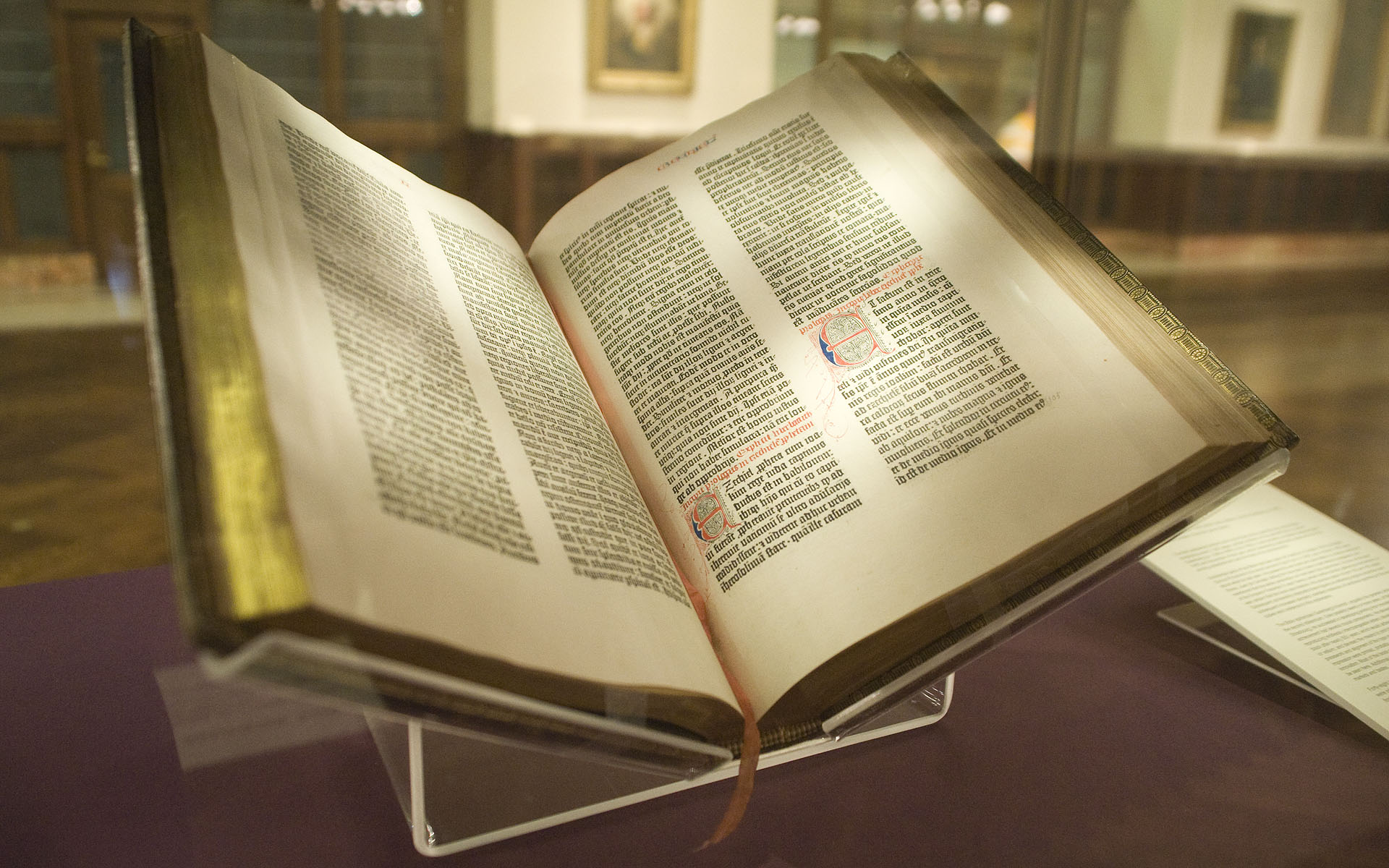

The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures, some, all, or a variant of which are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, Islam, the Baha'i Faith, and many other Abrahamic religions. The Bible is an anthology, a compilation of texts of a variety of forms, originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. These texts include instructions, stories, poetry, and prophecies, among other genres. The collection of materials that are accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers in the Bible generally consider it to be a product of divine inspiration, but the way they understand what that means and interpret the text varies.

Several terms redirect here. For other uses, see Bible (disambiguation), Biblical (disambiguation), and The Holy Bible (disambiguation).

The religious texts were compiled by different religious communities into various official collections. The earliest contained the first five books of the Bible, called the Torah in Hebrew and the Pentateuch (meaning five books) in Greek. The second oldest part was a collection of narrative histories and prophecies (the Nevi'im). The third collection (the Ketuvim) contains psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories. "Tanakh" is an alternate term for the Hebrew Bible composed of the first letters of those three parts of the Hebrew scriptures: the Torah ("Teaching"), the Nevi'im ("Prophets"), and the Ketuvim ("Writings"). The Masoretic Text is the medieval version of the Tanakh, in Hebrew and Aramaic, that is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible by modern Rabbinic Judaism. The Septuagint is a Koine Greek translation of the Tanakh from the third and second centuries BC; it largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible.

Christianity began as an outgrowth of Second Temple Judaism, using the Septuagint as the basis of the Old Testament. The early Church continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what it saw as inspired, authoritative religious books. The gospels, Pauline epistles, and other texts quickly coalesced into the New Testament.

With estimated total sales of over five billion copies, the Bible is the best-selling publication of all time. It has had a profound influence both on Western culture and history and on cultures around the globe. The study of it through biblical criticism has indirectly impacted culture and history as well. The Bible is currently translated or is being translated into about half of the world's languages.

Etymology

The term "Bible" can refer to the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Bible, which contains both the Old and New Testaments.[1]

The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία, romanized: ta biblia, meaning "the books" (singular βιβλίον, biblion).[2]

The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of "scroll" and came to be used as the ordinary word for "book".[3] It is the diminutive of βύβλος byblos, "Egyptian papyrus", possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician sea port Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.[4]

The Greek ta biblia ("the books") was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books".[5] The biblical scholar F. F. Bruce notes that John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer (in his Homilies on Matthew, delivered between 386 and 388 CE) to use the Greek phrase ta biblia ("the books") to describe both the Old and New Testaments together.[6]

Latin biblia sacra "holy books" translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, "the holy books").[7] Medieval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra "holy book". It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.[8]

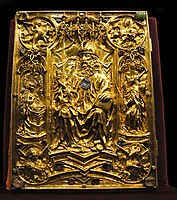

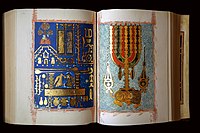

The grandest medieval Bibles were illuminated manuscripts in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders (marginalia) and miniature illustrations. Up to the 12th century, most manuscripts were produced in monasteries in order to add to the library or after receiving a commission from a wealthy patron. Larger monasteries often contained separate areas for the monks who specialized in the production of manuscripts called a scriptorium, where "separate little rooms were assigned to book copying; they were situated in such a way that each scribe had to himself a window open to the cloister walk."[304] By the 14th century, the cloisters of monks writing in the scriptorium started to employ laybrothers from the urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome and the Netherlands.[305]

Demand for manuscripts grew to an extent that the Monastic libraries were unable to meet with the demand, and began employing secular scribes and illuminators.[306] These individuals often lived close to the monastery and, in certain instances, dressed as monks whenever they entered the monastery, but were allowed to leave at the end of the day.[307] A notable example of an illuminated manuscript is the Book of Kells, produced circa the year 800 containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables.

The manuscript was "sent to the rubricator, who added (in red or other colours) the titles, headlines, the initials of chapters and sections, the notes and so on; and then – if the book was to be illustrated – it was sent to the illuminator."[308] In the case of manuscripts that were sold commercially, the writing would "undoubtedly have been discussed initially between the patron and the scribe (or the scribe's agent,) but by the time that the written gathering were sent off to the illuminator there was no longer any scope for innovation."[309]