Europa building

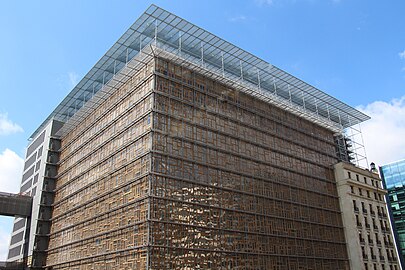

The Europa building is the seat of the European Council and Council of the European Union, located on the Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat in the European Quarter of Brussels, Belgium.[1] Its defining feature is the multi-storey "lantern-shaped" construct holding the main meeting rooms; a representation of which has been adopted by both the European Council and Council of the EU as their official emblems.[2]

This article is about the seat of two EU institutions. For other buildings, see Europa (disambiguation).Europa building

Résidence Palace - Bloc A

1040 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region

Belgium

Seat of the European Council and Council of the European Union

1922

1927

November 2007–December 2016

€321 million

70,646 m2 (760,430 sq ft)

Philippe Samyn and Partners (architects & engineers, Lead and Design Partner)

Studio Valle Progettazioni

Buro Happold

Jan De Nul Group (contractor, Lead and Construction Partner)

The Europa building is situated on the former site of the partially demolished and renovated Bloc A of the Résidence Palace, a complex of luxurious apartment blocks. Its exterior combines the listed Art Deco façade of the original 1920s building with the contemporary design of the architect Philippe Samyn. The building is linked via two skyways and a service tunnel to the adjacent Justus Lipsius building, which provides for additional office space, meeting rooms and press facilities.

History[edit]

Construction and former usage: the Résidence Palace[edit]

Following the end of the First World War, the Walloon businessman Lucien Kaisin, in collaboration with the Swiss-Belgian architect Michel Polak, put forward plans for a complex of luxurious apartment blocks for the bourgeoisie and aristocracy, the Résidence Palace, to be situated on the edge of Brussels' Leopold Quarter. Consisting of five "Blocs" (A–E), it was to be "a small town within a city" able to provide its residents with onsite facilities, including a theatre hall, a swimming pool, as well as other commercial services such as a restaurants and hairdressers.[3] The Résidence Palace aimed to address the dual shortage of suitable property and domestic workers for the upper classes following the destruction brought about during the war. The foundation stone of the Art Deco building was laid on 30 May 1923 with the first residents moving in 1927.

The development, however, only had a short commercial success. In 1940, tenants were forced to leave,[4] as the building was requisitioned as the headquarters of the occupying German army during the Second World War.[5] In September 1944, after the liberation of Brussels, the building was taken over as headquarters for the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) and the RAF Second Tactical Air Force.[6] After the war, in 1947, the Belgian Government bought the complex and used Bloc A (the north-eastern L-shaped building) for administrative offices.[7] At the end of the 1960s, as part of work to modernise the area during the construction of an underground railway line beneath the Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat, a new aluminium façade was built, closing the L-shape, under the supervision of Michel Polak's sons.

A defining characteristic of the Europa building is the use of striking colour compositions designed by the painter Georges Meurant. The lead architect, Philipe Samyn, wished to break with the visual "uniformity" of other EU buildings, believing that the EU was "not being served well by its blue flag with its 12 stars".[14] Further, he believed it "too bland an image of the multiple institutional, social, cultural constellations that structure European conscience". Samyn, inspired by the boldness of the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas' 2002 "barcode" flag, commissioned Meurant to reflect the national heraldic symbols and flags, of the 28 member states in their diverse proportions and colours.[14] Meurant's orthogonal polychrome grid designs appear over ceilings in meeting rooms, doors, carpet flooring in conference rooms, as well as in the corridors, press room, catering facilities and elevators.[14] Samyn and Meurant saw this as a way to not only bring more light and a warmer atmosphere into the building, and particular in the meeting rooms, which for security reasons had to remain windowless, but also to create a visual message, of "permanent creative effort and political debate" befitting a polyglottic diverse Union.[14]