Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French Arts décoratifs (lit. 'Decorative Arts'),[1] is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in Paris in the 1910s (just before World War I),[2] and flourished in the United States and Europe during the 1920s to early 1930s. Through styling and design of the exterior and interior of anything from large structures to small objects, including how people look (clothing, fashion, and jewelry), Art Deco has influenced bridges, buildings (from skyscrapers to cinemas), ships, ocean liners, trains, cars, trucks, buses, furniture, and everyday objects including radios and vacuum cleaners.[3]

This article is about the art style. For other uses, see Art Deco (disambiguation).Years active

c. 1910s–1950s

Global

Art Deco got its name after the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) held in Paris.[4] Art Deco combined the styles of early 20th century Modernist avant-garde, with the fine craftsmanship and rich materials of French historic design, but also sometimes with motifs taken from non-Western cultures. From its outset, Art Deco was influenced by the bold geometric forms of Cubism and the Vienna Secession; the bright colours of Fauvism and of the Ballets Russes; the updated craftsmanship of the furniture of the eras of Louis XVI and Louis Philippe I; and the exoticized styles of art from China, Japan, India, Persia, ancient Egypt and Maya.

During its heyday, Art Deco represented luxury, glamour, exuberance, and faith in social and technological progress. The movement featured rare and expensive materials, such as ebony and ivory, and exquisite craftsmanship. It also introduced new materials such as chrome plating, stainless steel and plastic. In New York, the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and other buildings from the 1920s and 1930s are monuments to the style.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Art Deco gradually became more subdued. A sleeker form of the style, called Streamline Moderne, appeared in the 1930s, featuring curving forms and smooth, polished surfaces.[5] Art Deco was a truly international style, but its dominance ended with the beginning of World War II and the rise of the strictly functional and unadorned styles of modern architecture and the International Style of architecture that followed.[6][7]

Etymology[edit]

Art Deco took its name, short for Arts Décoratifs, from the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925,[4] though the diverse styles that characterised it had already appeared in Paris and Brussels before World War I.

Arts décoratifs was first used in France in 1858 in the Bulletin de la Société française de photographie.[8] In 1868, the Le Figaro newspaper used the term objets d'art décoratifs for objects for stage scenery created for the Théâtre de l'Opéra.[9][10][11] In 1875, furniture designers, textile, jewellers, glass-workers, and other craftsmen were officially given the status of artists by the French government. In response, the École royale gratuite de dessin (Royal Free School of Design), founded in 1766 under King Louis XVI to train artists and artisans in crafts relating to the fine arts, was renamed the École nationale des arts décoratifs (National School of Decorative Arts). It took its present name, ENSAD (École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs), in 1927.

The actual term art déco did not appear in print until 1966, in the title of the first modern exhibition on the subject, held by the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, Les Années 25 : Art déco, Bauhaus, Stijl, Esprit nouveau, which covered a variety of major styles in the 1920s and 1930s.[12] The term was then used in a 1966 newspaper article by Hillary Gelson in The Times (London, 12 November), describing the different styles at the exhibit.[13]

Art Deco gained currency as a broadly applied stylistic label in 1968 when historian Bevis Hillier published the first major academic book on it, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.[3] He noted that the term was already being used by art dealers, and cites The Times (2 November 1966) and an essay named Les Arts Déco in Elle magazine (November 1967) as examples.[14] In 1971, he organized an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which he details in his book The World of Art Deco.[15][16]

In its time, Art Deco was tagged with other names, like style moderne, Moderne, modernistic or style contemporain, and was not recognized as a distinct and homogenous style.[7]

Origins[edit]

Society of Decorative Artists (1901–1945)[edit]

The emergence of Art Deco was closely connected with the rise in status of decorative artists, who until late in the 19th century were considered simply artisans. The term arts décoratifs had been invented in 1875, giving the designers of furniture, textiles, and other decoration official status. The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists), or SAD, was founded in 1901, and decorative artists were given the same rights of authorship as painters and sculptors. A similar movement developed in Italy. The first international exhibition devoted entirely to the decorative arts, the Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Decorativa Moderna, was held in Turin in 1902. Several new magazines devoted to decorative arts were founded in Paris, including Arts et décoration and L'Art décoratif moderne. Decorative arts sections were introduced into the annual salons of the Sociéte des artistes français, and later in the Salon d'Automne. French nationalism also played a part in the resurgence of decorative arts, as French designers felt challenged by the increasing exports of less expensive German furnishings. In 1911, SAD proposed a major new international exposition of decorative arts in 1912. No copies of old styles would be permitted, only modern works. The exhibit was postponed until 1914; and then, because of the war, until 1925, when it gave its name to the whole family of styles known as "Déco".[17]

The event that marked the zenith of the style and gave it its name was the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts which took place in Paris from April to October in 1925. This was officially sponsored by the French government, and covered a site in Paris of 55 acres, running from the Grand Palais on the right bank to Les Invalides on the left bank, and along the banks of the Seine. The Grand Palais, the largest hall in the city, was filled with exhibits of decorative arts from the participating countries. There were 15,000 exhibitors from twenty different countries, including Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the new Soviet Union. Germany was not invited because of tensions after the war; the United States, misunderstanding the purpose of the exhibit, declined to participate. The event was visited by sixteen million people during its seven-month run. The rules of the exhibition required that all work be modern; no historical styles were allowed. The main purpose of the Exhibit was to promote the French manufacturers of luxury furniture, porcelain, glass, metalwork, textiles, and other decorative products. To further promote the products, all the major Paris department stores, and major designers had their own pavilions. The Exposition had a secondary purpose in promoting products from French colonies in Africa and Asia, including ivory and exotic woods.

The Hôtel du Collectionneur was a popular attraction at the Exposition; it displayed the new furniture designs of Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, as well as Art Deco fabrics, carpets, and a painting by Jean Dupas. The interior design followed the same principles of symmetry and geometric forms which set it apart from Art Nouveau, and bright colours, fine craftsmanship rare and expensive materials which set it apart from the strict functionality of the Modernist style. While most of the pavilions were lavishly decorated and filled with hand-made luxury furniture, two pavilions, those of the Soviet Union and Pavilion de L'Esprit Nouveau, built by the magazine of that name run by Le Corbusier, were built in an austere style with plain white walls and no decoration; they were among the earliest examples of modernist architecture.[78]

In 1925, two different competing schools coexisted within Art Deco: the traditionalists, who had founded the Society of Decorative Artists; included the furniture designer Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jean Dunand, the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, and designer Paul Poiret; they combined modern forms with traditional craftsmanship and expensive materials. On the other side were the modernists, who increasingly rejected the past and wanted a style based upon advances in new technologies, simplicity, a lack of decoration, inexpensive materials, and mass production. The modernists founded their own organisation, The French Union of Modern Artists, in 1929. Its members included architects Pierre Chareau, Francis Jourdain, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Corbusier, and, in the Soviet Union, Konstantin Melnikov; the Irish designer Eileen Gray; the French designer Sonia Delaunay; and the jewellers Georges Fouquet and Jean Puiforcat. They fiercely attacked the traditional art deco style, which they said was created only for the wealthy, and insisted that well-constructed buildings should be available to everyone, and that form should follow function. The beauty of an object or building resided in whether it was perfectly fit to fulfil its function. Modern industrial methods meant that furniture and buildings could be mass-produced, not made by hand.[79][80]

The Art Deco interior designer Paul Follot defended Art Deco in this way: "We know that man is never content with the indispensable and that the superfluous is always needed...If not, we would have to get rid of music, flowers, and perfumes..!"[81] However, Le Corbusier was a brilliant publicist for modernist architecture; he stated that a house was simply "a machine to live in", and tirelessly promoted the idea that Art Deco was the past and modernism was the future. Le Corbusier's ideas were gradually adopted by architecture schools, and the aesthetics of Art Deco were abandoned. The same features that made Art Deco popular in the beginning, its craftsmanship, rich materials and ornament, led to its decline. The Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929, and reached Europe shortly afterwards, greatly reduced the number of wealthy clients who could pay for the furnishings and art objects. In the Depression economic climate, few companies were ready to build new skyscrapers.[35] Even the Ruhlmann firm resorted to producing pieces of furniture in series, rather than individual hand-made items. The last buildings built in Paris in the new style were the Museum of Public Works by Auguste Perret (now the French Economic, Social and Environmental Council), the Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma, and the Palais de Tokyo of the 1937 Paris International Exposition; they looked out at the grandiose pavilion of Nazi Germany, designed by Albert Speer, which faced the equally grandiose socialist-realist pavilion of Stalin's Soviet Union.

After World War II, the dominant architectural style became the International Style pioneered by Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe. A handful of Art Deco hotels were built in Miami Beach after World War II, but elsewhere the style largely vanished, except in industrial design, where it continued to be used in automobile styling and products such as jukeboxes. In the 1960s, it experienced a modest academic revival, thanks in part to the writings of architectural historians such as Bevis Hillier. In the 1970s efforts were made in the United States and Europe to preserve the best examples of Art Deco architecture, and many buildings were restored and repurposed. Postmodern architecture, which first appeared in the 1980s, like Art Deco, often includes purely decorative features.[35][62][82][83] Deco continues to inspire designers, and is often used in contemporary fashion, jewellery, and toiletries.[84]

There was no section set aside for painting at the 1925 Exposition. Art deco painting was by definition decorative, designed to decorate a room or work of architecture, so few painters worked exclusively in the style, but two painters are closely associated with Art Deco. Jean Dupas painted Art Deco murals for the Bordeaux Pavilion at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris, and also painted the picture over the fireplace in the Maison du Collectionneur exhibit at the 1925 Exposition, which featured furniture by Ruhlmann and other prominent Art Deco designers. His murals were also prominent in the décor of the French ocean liner SS Normandie. His work was purely decorative, designed as a background or accompaniment to other elements of the décor.[85]

The other painter closely associated with the style is Tamara de Lempicka. Born in Poland, she emigrated to Paris after the Russian Revolution. She studied under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and borrowed many elements from their styles. She painted portraits in a realistic, dynamic and colourful Art Deco style.[86]

In the 1930s, a dramatic new form of Art Deco painting appeared in the United States. During the Great Depression, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration was created to give work to unemployed artists. Many were given the task of decorating government buildings, hospitals and schools. There was no specific art deco style used in the murals; artists engaged to paint murals in government buildings came from many different schools, from American regionalism to social realism; they included Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent and the Mexican painter Diego Rivera. The murals were Art Deco because they were all decorative and related to the activities in the building or city where they were painted: Reginald Marsh and Rockwell Kent both decorated U.S. postal buildings, and showed postal employees at work while Diego Rivera depicted automobile factory workers for the Detroit Institute of Arts. Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads (1933) for 30 Rockefeller Plaza featured an unauthorized portrait of Lenin.[87][88] When Rivera refused to remove Lenin, the painting was destroyed and a new mural was painted by the Spanish artist Josep Maria Sert.[89][90][91]

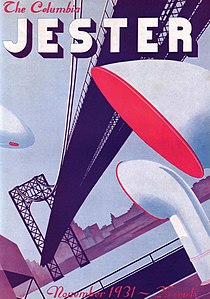

The Art Deco style appeared early in the graphic arts, in the years just before World War I. It appeared in Paris in the posters and the costume designs of Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes, and in the catalogues of the fashion designers Paul Poiret.[100] The illustrations of Georges Barbier, and Georges Lepape and the images in the fashion magazine La Gazette du bon ton perfectly captured the elegance and sensuality of the style. In the 1920s, the look changed; the fashions stressed were more casual, sportive and daring, with the woman models usually smoking cigarettes. American fashion magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper's Bazaar quickly picked up the new style and popularized it in the United States. It also influenced the work of American book illustrators such as Rockwell Kent. In Germany, the most famous poster artist of the period was Ludwig Hohlwein, who created colourful and dramatic posters for music festivals, beers, and, late in his career, for the Nazi Party.[101]

During the Art Nouveau period, posters usually advertised theatrical products or cabarets. In the 1920s, travel posters, made for steamship lines and airlines, became extremely popular. The style changed notably in the 1920s, to focus attention on the product being advertised. The images became simpler, precise, more linear, more dynamic, and were often placed against a single-color background. In France, popular Art Deco designers included Charles Loupot and Paul Colin, who became famous for his posters of American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Jean Carlu designed posters for Charlie Chaplin movies, soaps, and theatres; in the late 1930s he emigrated to the United States, where, during the World War, he designed posters to encourage war production. The designer Charles Gesmar became famous making posters for the singer Mistinguett and for Air France. Among the best-known French Art Deco poster designers was Cassandre, who made the celebrated poster of the ocean liner SS Normandie in 1935.[101]

In the 1930s a new genre of posters appeared in the United States during the Great Depression. The Federal Art Project hired American artists to create posters to promote tourism and cultural events.

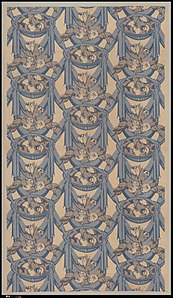

Decoration in the Art Deco period went through several distinct phases. Between 1910 and 1920, as Art Nouveau was exhausted, design styles saw a return to tradition, particularly in the work of Paul Iribe. In 1912 André Vera published an essay in the magazine L'Art Décoratif calling for a return to the craftsmanship and materials of earlier centuries and using a new repertoire of forms taken from nature, particularly baskets and garlands of fruit and flowers. A second tendency of Art Deco, also from 1910 to 1920, was inspired by the bright colours of the artistic movement known as the Fauves and by the colourful costumes and sets of the Ballets Russes. This style was often expressed with exotic materials such as sharkskin, mother of pearl, ivory, tinted leather, lacquered and painted wood, and decorative inlays on furniture that emphasized its geometry. This period of the style reached its high point in the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts. In the late 1920s and the 1930s, the decorative style changed, inspired by new materials and technologies. It became sleeker and less ornamental. Furniture, like architecture, began to have rounded edges and to take on a polished, streamlined look, taken from the streamline modern style. New materials, such as nickel or chrome-plated steel, aluminium and bakelite, an early form of plastic, began to appear in furniture and decoration.[123]

Throughout the Art Deco period, and particularly in the 1930s, the motifs of the décor expressed the function of the building. Theatres were decorated with sculpture which illustrated music, dance, and excitement; power companies showed sunrises, the Chrysler building showed stylized hood ornaments; The friezes of Palais de la Porte Dorée at the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition showed the faces of the different nationalities of French colonies. The Streamline style made it appear that the building itself was in motion. The WPA murals of the 1930s featured ordinary people; factory workers, postal workers, families and farmers, in place of classical heroes.[124]

Art Deco, like the complex times that engendered it, can best be characterized by a series of contradictions: minimalist vs maximalist, angular vs fluid, ziggurat vs streamline, symmetrical vs irregular, to name a few. The iconography chosen by Art Deco artists to express the period is also laden with contradictions. Fair maidens in 18th-century dress seem to coexist with chic sophisticated ladies and recumbent nudes, and flashes of lighting illuminate stylized rosebuds.[126]

French furniture from 1910 until the early 1920s was largely an updating of French traditional furniture styles, and the art nouveau designs of Louis Majorelle, Charles Plumet and other manufacturers. French furniture manufacturers felt threatened by the growing popularity of German manufacturers and styles, particularly the Biedermeier style, which was simple and clean-lined. The French designer Frantz Jourdain, the President of the Paris Salon d'Automne, invited designers from Munich to participate in the 1910 Salon. French designers saw the new German style and decided to meet the German challenge. The French designers decided to present new French styles in the Salon of 1912. The rules of the Salon indicated that only modern styles would be permitted. All of the major French furniture designers took part in Salon: Paul Follot, Paul Iribe, Maurice Dufrêne, André Groult, André Mare and Louis Suë took part, presenting new works that updated the traditional French styles of Louis XVI and Louis Philippe with more angular corners inspired by Cubism and brighter colours inspired by Fauvism and the Nabis.[127]

The painter André Mare and furniture designer Louis Süe both participated the 1912 Salon. After the war the two men joined to form their own company, formally called the Compagnie des Arts Française, but usually known simply as Suë and Mare. Unlike the prominent art nouveau designers like Louis Majorelle, who personally designed every piece, they assembled a team of skilled craftsmen and produced complete interior designs, including furniture, glassware, carpets, ceramics, wallpaper and lighting. Their work featured bright colors and furniture and fine woods, such as ebony encrusted with mother of pearl, abalone and silvered metal to create bouquets of flowers. They designed everything from the interiors of ocean liners to perfume bottles for the label of Jean Patou.The firm prospered in the early 1920s, but the two men were better craftsmen than businessmen. The firm was sold in 1928, and both men left.[128]

The most prominent furniture designer at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition was Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, from Alsace. He first exhibited his works at the 1913 Autumn Salon, then had his own pavilion, the "House of the Rich Collector", at the 1925 Exposition. He used only most rare and expensive materials, including ebony, mahogany, rosewood, ambon and other exotic woods, decorated with inlays of ivory, tortoise shell, mother of pearl, Little pompoms of silk decorated the handles of drawers of the cabinets.[129] His furniture was based upon 18th-century models, but simplified and reshaped. In all of his work, the interior structure of the furniture was completely concealed. The framework usually of oak, was completely covered with an overlay of thin strips of wood, then covered by a second layer of strips of rare and expensive woods. This was then covered with a veneer and polished, so that the piece looked as if it had been cut out of a single block of wood. Contrast to the dark wood was provided by inlays of ivory, and ivory key plates and handles. According to Ruhlmann, armchairs had to be designed differently according to the functions of the rooms where they appeared; living room armchairs were designed to be welcoming, office chairs comfortable, and salon chairs voluptuous. Only a small number of pieces of each design of furniture was made, and the average price of one of his beds or cabinets was greater than the price of an average house.[130]

Jules Leleu was a traditional furniture designer who moved smoothly into Art Deco in the 1920s; he designed the furniture for the dining room of the Élysée Palace, and for the first-class cabins of the steamship Normandie. his style was characterized by the use of ebony, Macassar wood, walnut, with decoration of plaques of ivory and mother of pearl. He introduced the style of lacquered art deco furniture in the late 1920s, and in the late 1930s introduced furniture made of metal with panels of smoked glass.[131] In Italy, the designer Gio Ponti was famous for his streamlined designs.

The costly and exotic furniture of Ruhlmann and other traditionalists infuriated modernists, including the architect Le Corbusier, causing him to write a famous series of articles denouncing the arts décoratif style. He attacked furniture made only for the rich and called upon designers to create furniture made with inexpensive materials and modern style, which ordinary people could afford. He designed his own chairs, created to be inexpensive and mass-produced.[132]

In the 1930s, furniture designs adapted to the form, with smoother surfaces and curved forms. The masters of the late style included Donald Deskey, who was one of the most influential designers; he created the interior of the Radio City Music Hall. He used a mixture of traditional and very modern materials, including aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic.[133] Other top designers of Art Deco furniture of the 1930s in the United States included Gilbert Rohde, Warren McArthur, and Kem Weber.

The Waterfall style was popular in the 1930s and 1940s, the most prevalent Art Deco form of furniture at the time. Pieces were typically of plywood finished with blond veneer and with rounded edges, resembling a waterfall.[134]

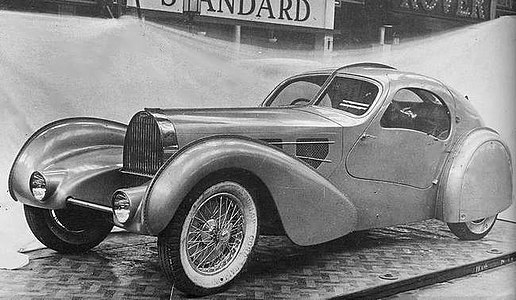

Streamline was a variety of Art Deco which emerged during the mid-1930s. It was influenced by modern aerodynamic principles developed for aviation and ballistics to reduce aerodynamic drag at high velocities. The bullet shapes were applied by designers to cars, trains, ships, and even objects not intended to move, such as refrigerators, gas pumps, and buildings.[64] One of the first production vehicles in this style was the Chrysler Airflow of 1933. It was unsuccessful commercially, but the beauty and functionality of its design set a precedent; meant modernity. It continued to be used in car design well after World War II.[135][136][137][138]

New industrial materials began to influence the design of cars and household objects. These included aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic. Bakelite could be easily moulded into different forms, and soon was used in telephones, radios and other appliances.

Ocean liners also adopted a style of Art Deco, known in French as the Style Paquebot, or "Ocean Liner Style". The most famous example was the SS Normandie, which made its first transatlantic trip in 1935. It was designed particularly to bring wealthy Americans to Paris to shop. The cabins and salons featured the latest Art Deco furnishings and decoration. The Grand Salon of the ship, which was the restaurant for first-class passengers, was bigger than the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles. It was illuminated by electric lights within twelve pillars of Lalique crystal; thirty-six matching pillars lined the walls. This was one of the earliest examples of illumination being directly integrated into architecture. The style of ships was soon adapted to buildings. A notable example is found on the San Francisco waterfront, where the Maritime Museum building, built as a public bath in 1937, resembles a ferryboat, with ship railings and rounded corners. The Star Ferry Terminal in Hong Kong also used a variation of the style.[35]

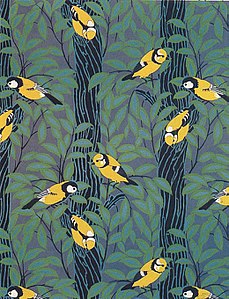

Textiles were an important part of the Art Deco style, in the form of colourful wallpaper, upholstery and carpets, In the 1920s, designers were inspired by the stage sets of the Ballets Russes, fabric designs and costumes from Léon Bakst and creations by the Wiener Werkstätte. The early interior designs of André Mare featured brightly coloured and highly stylized garlands of roses and flowers, which decorated the walls, floors, and furniture. Stylized Floral motifs also dominated the work of Raoul Dufy and Paul Poiret, and in the furniture designs of J.E. Ruhlmann. The floral carpet was reinvented in Deco style by Paul Poiret.[139]

The use of the style was greatly enhanced by the introduction of the pochoir stencil-based printing system, which allowed designers to achieve crispness of lines and very vivid colours. Art Deco forms appeared in the clothing of Paul Poiret, Charles Worth and Jean Patou. After World War I, exports of clothing and fabrics became one of the most important currency earners of France.[140]

Late Art Deco wallpaper and textiles sometimes featured stylized industrial scenes, cityscapes, locomotives and other modern themes, as well as stylized female figures, metallic finishes and geometric designs.[140]

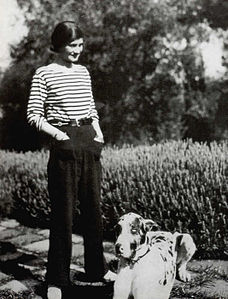

The new woman of pre-WW1 days became the Amazon of the Art Deco era. Fashion changed dramatically during this period, thanks in particular to designers Paul Poiret and later Coco Chanel. Poiret introduced an important innovation to fashion design, the concept of draping, a departure from the tailoring and patternmaking of the past.[141] He designed clothing cut along straight lines and constructed of rectangular motifs.[141] His styles offered structural simplicity[141] The corseted look and formal styles of the previous period were abandoned, and fashion became more practical, and streamlined. with the use of new materials, brighter colours and printed designs.[141] The designer Coco Chanel continued the transition, popularising the style of sporty, casual chic.[142]

A particular typology of the era was the Flapper, a woman who cut her hair into a short bob, drank cocktails, smoked in public, and danced late into the night at fashionable clubs, cabarets or bohemian dives. Of course, most women didn't live like this, the Flapper being more a character present in popular imagination than a reality. Another female Art Deco style was the androgynous garçonne of the 1920s, with flattened bosom, dispelled waist and revealed legs, reducing the silhouette to a short tube, topped with a head-hugging cloche hat.[143]

In the 1920s and 1930s, designers including René Lalique and Cartier tried to reduce the traditional dominance of diamonds by introducing more colourful gemstones, such as small emeralds, rubies and sapphires. They also placed greater emphasis on very elaborate and elegant settings, featuring less-expensive materials such as enamel, glass, horn and ivory. Diamonds themselves were cut in less traditional forms; the 1925 Exposition saw many diamonds cut in the form of tiny rods or matchsticks. Other popular Art Deco cuts include:

The settings for diamonds also changed; More and more often jewellers used platinum instead of gold, since it was strong and flexible, and could set clusters of stones. Jewellers also began to use more dark materials, such as enamels and black onyx, which provided a higher contrast with diamonds.[146]

Jewellery became much more colourful and varied in style. Cartier and the firm of Boucheron combined diamonds with colourful other gemstones cut into the form of leaves, fruit or flowers, to make brooches, rings, earrings, clips and pendants. Far Eastern themes also became popular; plaques of jade and coral were combined with platinum and diamonds, and vanity cases, cigarette cases and powder boxes were decorated with Japanese and Chinese landscapes made with mother of pearl, enamel and lacquer.[146]

Rapidly changing fashions in clothing brought new styles of jewellery. Sleeveless dresses of the 1920s meant that arms needed decoration, and designers quickly created bracelets of gold, silver and platinum encrusted with lapis-lazuli, onyx, coral, and other colourful stones; Other bracelets were intended for the upper arms, and several bracelets were often worn at the same time. The short haircuts of women in the twenties called for elaborate deco earring designs. As women began to smoke in public, designers created very ornate cigarette cases and ivory cigarette holders. The invention of the wristwatch before World War I inspired jewelers to create extraordinary, decorated watches, encrusted with diamonds and plated with enamel, gold and silver. Pendant watches, hanging from a ribbon, also became fashionable.[147]

The established jewellery houses of Paris in the period, Cartier, Chaumet, Georges Fouquet, Mauboussin, and Van Cleef & Arpels all created jewellery and objects in the new fashion. The firm of Chaumet made highly geometric cigarette boxes, cigarette lighters, pillboxes and notebooks, made of hard stones decorated with jade, lapis lazuli, diamonds and sapphires. They were joined by many young new designers, each with his own idea of deco. Raymond Templier designed pieces with highly intricate geometric patterns, including silver earrings that looked like skyscrapers. Gerard Sandoz was only 18 when he started to design jewelry in 1921; he designed many celebrated pieces based on the smooth and polished look of modern machinery. The glass designer René Lalique also entered the field, creating pendants of fruit, flowers, frogs, fairies or mermaids made of sculpted glass in bright colors, hanging on cords of silk with tassels.[147] The jeweller Paul Brandt contrasted rectangular and triangular patterns, and embedded pearls in lines on onyx plaques. Jean Despres made necklaces of contrasting colours by bringing together silver and black lacquer, or gold with lapis lazuli. Many of his designs looked like highly polished pieces of machines. Jean Dunand was also inspired by modern machinery, combined with bright reds and blacks contrasting with polished metal.[147]

Like the Art Nouveau period before it, Art Deco was an exceptional period for fine glass and other decorative objects, designed to fit their architectural surroundings. The most famous producer of glass objects was René Lalique, whose works, from vases to hood ornaments for automobiles, became symbols of the period. He had made ventures into glass before World War I, designing bottles for the perfumes of François Coty, but he did not begin serious production of art glass until after World War I. In 1918, at the age of 58, he bought a large glass works in Combs-la-Ville and began to manufacture both artistic and practical glass objects. He treated glass as a form of sculpture, and created statuettes, vases, bowls, lamps and ornaments. He used demi-crystal rather than lead crystal, which was softer and easier to form, though not as lustrous. He sometimes used coloured glass, but more often used opalescent glass, where part or the whole of the outer surface was stained with a wash. Lalique provided the decorative glass panels, lights and illuminated glass ceilings for the ocean liners SS Île de France in 1927 and the SS Normandie in 1935, and for some of the first-class sleeping cars of the French railroads. At the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts, he had his own pavilion, designed a dining room with a table setting and matching glass ceiling for the Sèvres Pavilion, and designed a glass fountain for the courtyard of the Cours des Métiers, a slender glass column which spouted water from the sides and was illuminated at night.[149]

Other notable Art Deco glass manufacturers included Marius-Ernest Sabino, who specialized in figurines, vases, bowls, and glass sculptures of fish, nudes, and animals. For these he often used an opalescent glass which could change from white to blue to amber, depending upon the light. His vases and bowls featured molded friezes of animals, nudes or busts of women with fruit or flowers. His work was less subtle but more colourful than that of Lalique.[149]

Other notable Deco glass designers included Edmond Etling, who also used bright opalescent colours, often with geometric patterns and sculpted nudes; Albert Simonet, and Aristide Colotte and Maurice Marinot, who was known for his deeply etched sculptural bottles and vases. The firm of Daum from the city of Nancy, which had been famous for its Art Nouveau glass, produced a line of Deco vases and glass sculpture, solid, geometric and chunky in form. More delicate multi-coloured works were made by Gabriel Argy-Rousseau, who produced delicately shaded vases with sculpted butterflies and nymphs, and Francois Decorchemont, whose vases were streaked and marbled.[149]

The Great Depression ruined a large part of the decorative glass industry, which depended upon wealthy clients. Some artists turned to designing stained glass windows for churches. In 1937, the Steuben glass company began the practice of commissioning famous artists to produce glassware.[149] Louis Majorelle, famous for his Art Nouveau furniture, designed a remarkable Art Deco stained glass window portraying steel workers for the offices of the Aciéries de Longwy, a steel mill in Longwy, France.

Amiens Cathedral has a rare example of Art Deco stained glass windows in the Chapel of the Sacred Heart, made in 1932-34 by the Paris glass artist Jean Gaudin based on drawings by Jacques Le Breton.[150]

Art Deco artists produced a wide variety of practical objects in the Art Deco style, made of industrial materials from traditional wrought iron to chrome-plated steel. The American artist Norman Bel Geddes designed a cocktail set resembling a skyscraper made of chrome-plated steel. Raymond Subes designed an elegant metal grille for the entrance of the Palais de la Porte Dorée, the centre-piece of the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition. The French sculptor Jean Dunand produced magnificent doors on the theme "The Hunt", covered with gold leaf and paint on plaster (1935).[151]

Animation[edit]

Art Deco visuals and imagery was used in multiple animated films including Batman, Night Hood, All's Fair at the Fair, Merry Mannequins, Page Miss Glory, Fantasia and Sleeping Beauty.[152] The architecture is featured in the fictitious underwater city of Rapture in the BioShock video game series.

In many cities, efforts have been made to protect the remaining Art Deco buildings. In many U.S. cities, historic art deco cinemas have been preserved and turned into cultural centres. Even more modest art deco buildings have been preserved as part of America's architectural heritage; an art deco café and gas station along Route 66 in Shamrock, Texas is an historic monument. The Miami Beach Architectural District protects several hundred old buildings, and requires that new buildings comply with the style. In Havana, Cuba, many Art Deco buildings have badly deteriorated. Efforts are underway to bring the buildings back to their original appearance.

In the 21st century, modern variants of Art Deco, called Neo Art Deco (or neo-Art Deco), have appeared in some American cities, inspired by the classic Art Deco buildings of the 1920s and 1930s.[170] Examples include the NBC Tower in Chicago, inspired by 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City; and Smith Center for the Performing Arts in Las Vegas, Nevada, which includes art deco features from Hoover Dam, 80 km (50 miles) away.[170][171][172][173]

![Art Nouveau influences – Sinuous curves on the façade of Avenue Montaigne no. 26, Paris, by Louis Duhayon and Marcel Julien (1937)[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Avenue_Montaigne_%2847128639262%29.jpg/383px-Avenue_Montaigne_%2847128639262%29.jpg)

![The flower basket – Balconies and pediment of Avenue Montaigne no. 41 in Paris, unknown architect or sculptor (1924)[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/41_Avenue_Montaigne%2C_75008_Paris%2C_France_27_December_2016.jpg/180px-41_Avenue_Montaigne%2C_75008_Paris%2C_France_27_December_2016.jpg)

![Repeating patterns – Decorative ironwork of the Madison Belmont Building (Madison Avenue no. 181–183) in New York City, by Ferrobrandt (1925)[115]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Grille_of_the_Cheney_Silk_Company_Building%2C_New_York_City%2C_1925%2C_designed_by_the_French_metalworking_company_Ferrobrandt.jpg/176px-Grille_of_the_Cheney_Silk_Company_Building%2C_New_York_City%2C_1925%2C_designed_by_the_French_metalworking_company_Ferrobrandt.jpg)

![The papyrus flower – Porte d'honneur, at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, by Edgar Brandt (1925)[116]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Porte_d%27honneur%2C_by_Edgar_Brandt%2C_1925%2C_at_the_International_Exhibition_of_Modern_Decorative_and_Industrial_Arts.jpg/379px-Porte_d%27honneur%2C_by_Edgar_Brandt%2C_1925%2C_at_the_International_Exhibition_of_Modern_Decorative_and_Industrial_Arts.jpg)

![The foliage scroll – Elevator doors, by Brandt (1926), wrought iron, glass, patinated and gilded bronze, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon[117]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Edgar_brandt%2C_porte_da_ascensore_in_ferro%2C_vetro_e_bronzo%2C_francia_1926_02.jpg/178px-Edgar_brandt%2C_porte_da_ascensore_in_ferro%2C_vetro_e_bronzo%2C_francia_1926_02.jpg)

![The octagon-shaped medallion – Sign of the La Samaritaine department store in Paris, by Henri Sauvage (1928)[118]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Paris_La_Samaritaine_374.JPG/406px-Paris_La_Samaritaine_374.JPG)

![Vertical mouldings – Greybrook House (Brook Street no. 28) in London, by Sir John Burnet & Partners (1928–29)[119]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/28_Brook_Street%2C_Mayfair%2C_January_2022_01.jpg/202px-28_Brook_Street%2C_Mayfair%2C_January_2022_01.jpg)

![An aesthetic of artificial lighting – Maison de France (now showroom for Louis Vuitton), Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 101 in Paris, by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau and Charles-Henri Besnard (1931)[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Louis_Vuitton_Maison_Champs_%C3%89lys%C3%A9es_%2849570496372%29.jpg/360px-Louis_Vuitton_Maison_Champs_%C3%89lys%C3%A9es_%2849570496372%29.jpg)

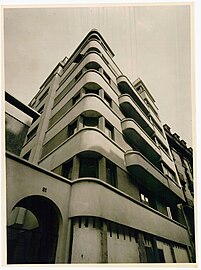

![Ziggurat – Union Hotel (Strada Ion Câmpineanu no. 11) in Bucharest, by Arghir Culina (1931)[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Bucharest_-_Strada_Ion_C%C3%A2mpineanu_11_%28cropped_top%29.jpg/251px-Bucharest_-_Strada_Ion_C%C3%A2mpineanu_11_%28cropped_top%29.jpg)

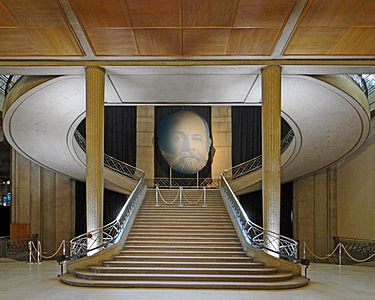

![Vertical and horizontal luminous surfaces – Entrance hall of the Villa Cavrois in Croix, France, by Rob Mallet-Stevens (1932)[121]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Villa_Cavrois_le_vestibule_%28cropped%29.jpg/192px-Villa_Cavrois_le_vestibule_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![The undulating line – Relief on the Grave of the Străjescu Family in Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, by George Cristinel (1934)[122]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/71/Grave_of_the_colonel_Paul_Str%C4%83jescu_Family_in_the_Bellu_Cemetery_in_Bucharest%2C_Romania_%2808%29.jpg/152px-Grave_of_the_colonel_Paul_Str%C4%83jescu_Family_in_the_Bellu_Cemetery_in_Bucharest%2C_Romania_%2808%29.jpg)

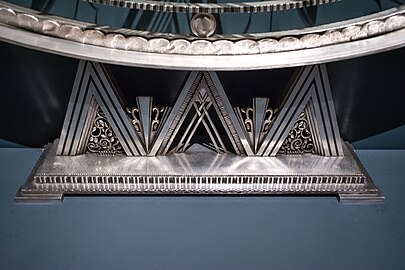

![Angular chandeliers by Lanchester & Lodge (c. 1929–1936), Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK[148]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dc/A_light_fixture_in_the_Leeds_Uni._library_%28353154643%29.jpg/200px-A_light_fixture_in_the_Leeds_Uni._library_%28353154643%29.jpg)

![Fiat Tagliero Building in Asmara, Eritrea, by Giuseppe Pettazzi (1938)[153]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/Fiat_tagliero%2C_08.JPG/441px-Fiat_tagliero%2C_08.JPG)

![Messeturm in Frankfurt, Germany, by Helmut Jahn (1990), a Postmodern building that is reminiscent of Art Deco architecture[168]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Messeturm%2C_Frankfurt%2C_Southwest_detail_view_20170325_1.jpg/184px-Messeturm%2C_Frankfurt%2C_Southwest_detail_view_20170325_1.jpg)

![Rue Henri Heine no. 3-5 in Paris by J.J. Ory (2001), a neo-Art Deco building[169]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Rue_Henri_Heine_3.jpg/400px-Rue_Henri_Heine_3.jpg)