Pancreas

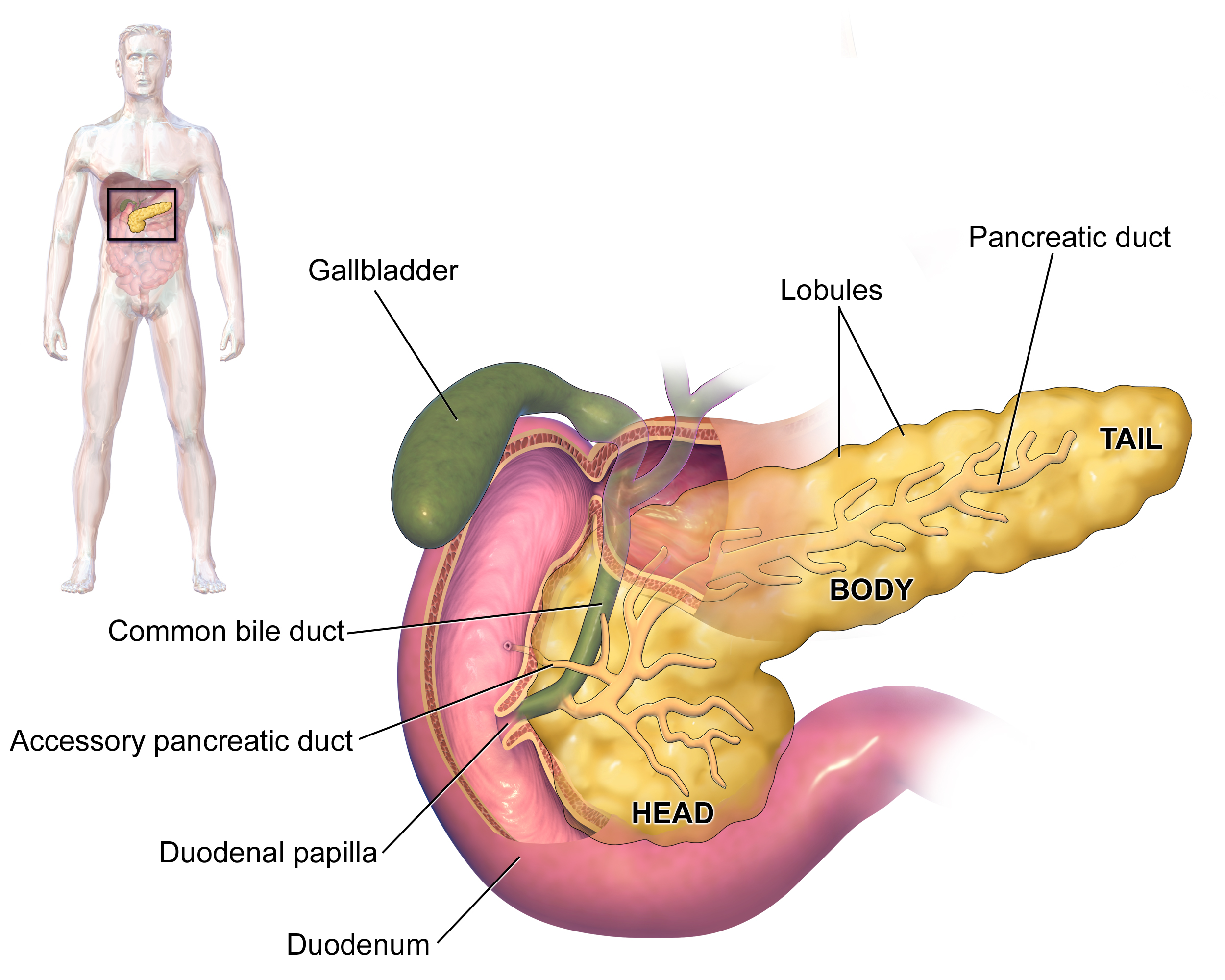

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e., it has both an endocrine and a digestive exocrine function.[2] 99% of the pancreas is exocrine and 1% is endocrine.[3][4][5][6] As an endocrine gland, it functions mostly to regulate blood sugar levels, secreting the hormones insulin, glucagon, somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide. As a part of the digestive system, it functions as an exocrine gland secreting pancreatic juice into the duodenum through the pancreatic duct. This juice contains bicarbonate, which neutralizes acid entering the duodenum from the stomach; and digestive enzymes, which break down carbohydrates, proteins and fats in food entering the duodenum from the stomach.

For other uses, see Pancreas (disambiguation).Pancreas

pancreas

πάγκρεας (pánkreas)

Inflammation of the pancreas is known as pancreatitis, with common causes including chronic alcohol use and gallstones. Because of its role in the regulation of blood sugar, the pancreas is also a key organ in diabetes mellitus. Pancreatic cancer can arise following chronic pancreatitis or due to other reasons, and carries a very poor prognosis, as it is often only identified after it has spread to other areas of the body.

The word pancreas comes from the Greek πᾶν (pân, "all") & κρέας (kréas, "flesh"). The function of the pancreas in diabetes has been known since at least 1889, with its role in insulin production identified in 1921.

History[edit]

The pancreas was first identified by Herophilus (335–280 BC), a Greek anatomist and surgeon.[41] A few hundred years later, Rufus of Ephesus, another Greek anatomist, gave the pancreas its name. Etymologically, the term "pancreas", a modern Latin adaptation of Greek πάγκρεας,[42] [πᾶν ("all", "whole"), and κρέας ("flesh")],[43] originally means sweetbread,[44] although literally meaning all-flesh, presumably because of its fleshy consistency. It was only in 1889 when Oskar Minkowski discovered that removing the pancreas from a dog caused it to become diabetic.[45] Insulin was later isolated from pancreatic islets by Frederick Banting and Charles Best in 1921.[45]

The way the tissue of the pancreas has been viewed has also changed. Previously, it was viewed using simple staining methods such as H&E stains. Now, immunohistochemistry can be used to more easily differentiate cell types. This involves visible antibodies to the products of certain cell types, and helps identify with greater ease cell types such as alpha and beta cells.[9]

Other animals[edit]

Pancreatic tissue is present in all vertebrates, but its precise form and arrangement varies widely. There may be up to three separate pancreases, two of which arise from the pancreatic bud, and the other dorsally. In most species (including humans), these "fuse" in the adult, but there are several exceptions. Even when a single pancreas is present, two or three pancreatic ducts may persist, each draining separately into the duodenum (or equivalent part of the foregut). Birds, for example, typically have three such ducts.[46]

In teleost fish, and a few other species (such as rabbits), there is no discrete pancreas at all, with pancreatic tissue being distributed diffusely across the mesentery and even within other nearby organs, such as the liver or spleen. In a few teleost species, the endocrine tissue has fused to form a distinct gland within the abdominal cavity, but otherwise it is distributed among the exocrine components. The most primitive arrangement, however, appears to be that of lampreys and lungfish, in which pancreatic tissue is found as a number of discrete nodules within the wall of the gut itself, with the exocrine portions being little different from other glandular structures of the intestine.[46]

Cuisine[edit]

The pancreas of calf (ris de veau) or lamb (ris d'agneau), and, less commonly, of beef or pork, are used as food under the culinary name of sweetbread.[47][48]