Extended metaphor

An extended metaphor, also known as a conceit or sustained metaphor, is the use of a single metaphor or analogy at length in a work of literature. It differs from a mere metaphor in its length, and in having more than one single point of contact between the object described (the so-called tenor) and the comparison used to describe it (the vehicle).[1][2] These implications are repeatedly emphasized, discovered, rediscovered, and progressed in new ways.[2]

History of meaning[edit]

In the Renaissance, the term (which is related to the word concept) indicated the idea that informed a literary work—its theme. Later, it came to stand for the extended and heightened metaphor common in Renaissance poetry, and later still it came to denote the even more elaborate metaphors of 17th century poetry.

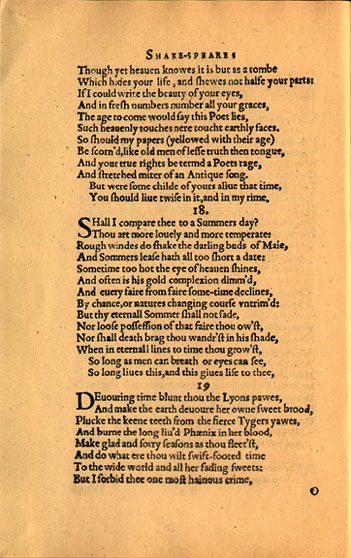

The Renaissance conceit, given its importance in Petrarch's Il Canzoniere, is also referred to as Petrarchan conceit. It is a comparison in which human experiences are described in terms of an outsized metaphor (a kind of metaphorical hyperbole)—as in Petrarch's comparison between the effect of the gaze of the beloved and the sun melting snow. The history of poetry reveals shows poets often outdoing their predecessors, like Shakespeare building on Petrarchan imagery in his Sonnet 130: "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun".[3]

The 17th-century and the sometimes so-called metaphysical poets extended the notion of the elaborate metaphor; their idea of conceit differs from an extended analogy in the sense that it does not have a clear-cut relationship between the things being compared.[3] Helen Gardner, in her study of the metaphysical poets, observed that "a conceit is a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness" and that "a comparison becomes a conceit when we are made to concede likeness while being strongly conscious of unlikeness."[4]

Metaphysical conceit[edit]

The metaphysical conceit is often imaginative, exploring specific parts of an experience.[8] A frequently cited example is found in John Donne's "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning", in which a couple faced with absence from each other is likened to the legs of a compass.[4][8] In comparison with the earlier conceit, the metaphysical conceit has a startling, unusual quality: Robert H. Ray described it as a "lengthy, far-fetched, ingenious analogy". The analogy is developed throughout multiple lines, sometimes the entire poem. Poet and critic Samuel Johnson was not enamored with this conceit, critiquing its use of "dissimilar images" and the "discovery of occult resemblances in things apparently unlike".[8] His judgment, that the conceit was a device in which "the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together",[9][10] is often cited and held sway until the early twentieth century, when poets like T. S. Eliot re-evaluated the English poetry of the seventeenth century.[11] Well-known poets employing this type of conceit include John Donne, Andrew Marvell, and George Herbert.[8]