Francisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (/ˈɡɔɪə/; Spanish: [fɾanˈθisko xoˈse ðe ˈɣoʝa i luˈθjentes]; 30 March 1746 – 16 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[1] His paintings, drawings, and engravings reflected contemporary historical upheavals and influenced important 19th- and 20th-century painters.[2] Goya is often referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns.[3]

"Goya" redirects here. For the food company, see Goya Foods. For other uses, see Goya (disambiguation).

Francisco de Goya

Josefa Bayeu (m. 1773)

Goya was born to a middle-class family in 1746, in Fuendetodos in Aragon. He studied painting from age 14 under José Luzán y Martinez and moved to Madrid to study with Anton Raphael Mengs. He married Josefa Bayeu in 1773. Goya became a court painter to the Spanish Crown in 1786 and this early portion of his career is marked by portraits of the Spanish aristocracy and royalty, and Rococo-style tapestry cartoons designed for the royal palace.

Although Goya's letters and writings survive, little is known about his thoughts. He had a severe and undiagnosed illness in 1793 that left him deaf, after which his work became progressively darker and more pessimistic. His later easel and mural paintings, prints and drawings appear to reflect a bleak outlook on personal, social and political levels, and contrast with his social climbing. He was appointed Director of the Royal Academy in 1795, the year Manuel Godoy made an unfavorable treaty with France. In 1799, Goya became Primer Pintor de Cámara (Prime Court Painter), the highest rank for a Spanish court painter. In the late 1790s, commissioned by Godoy, he completed his La maja desnuda, a remarkably daring nude for the time and clearly indebted to Diego Velázquez. In 1800–01, he painted Charles IV of Spain and His Family, also influenced by Velázquez.

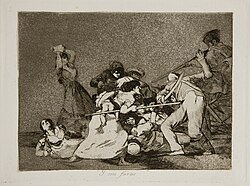

In 1807, Napoleon led the French army into the Peninsular War against Spain. Goya remained in Madrid during the war, which seems to have affected him deeply. Although he did not speak his thoughts in public, they can be inferred from his Disasters of War series of prints (although published 35 years after his death) and his 1814 paintings The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808. Other works from his mid-period include the Caprichos and Los Disparates etching series, and a wide variety of paintings concerned with insanity, mental asylums, witches, fantastical creatures and religious and political corruption, all of which suggest that he feared for both his country's fate and his own mental and physical health.

His late period culminates with the Black Paintings of 1819–1823, applied on oil on the plaster walls of his house the Quinta del Sordo (House of the Deaf Man) where, disillusioned by political and social developments in Spain, he lived in near isolation. Goya eventually abandoned Spain in 1824 to retire to the French city of Bordeaux, accompanied by his much younger maid and companion, Leocadia Weiss, who may have been his lover. There he completed his La Tauromaquia series and a number of other works. Following a stroke that left him paralyzed on his right side, Goya died and was buried on 16 April 1828 aged 82.

The French army invaded Spain in 1808, leading to the Peninsular War of 1808–1814. The extent of Goya's involvement with the court of the "intruder king", Joseph I, the brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, is not known; he painted works for French patrons and sympathisers, but kept neutral during the fighting. After the restoration of the Spanish King Ferdinand VII in 1814, Goya denied any involvement with the French. By the time of his wife Josefa's death in 1812, he was painting The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808, and preparing the series of etchings later known as The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra). Ferdinand VII returned to Spain in 1814 but relations with Goya were not cordial. The artist completed portraits of the king for a variety of ministries, but not for the king himself.

Although Goya did not make his intention known when creating The Disasters of War, art historians view them as a visual protest against the violence of the 1808 Dos de Mayo Uprising, the subsequent Peninsular War and the move against liberalism in the aftermath of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. The scenes are singularly disturbing, sometimes macabre in their depiction of battlefield horror, and represent an outraged conscience in the face of death and destruction.[49] They were not published until 1863, 35 years after his death. It is likely that only then was it considered politically safe to distribute a sequence of artworks criticising both the French and restored Bourbons.[50]

The first 47 plates in the series focus on incidents from the war and show the consequences of the conflict on individual soldiers and civilians. The middle series (plates 48 to 64) record the effects of the famine that hit Madrid in 1811–12, before the city was liberated from the French. The final 17 reflect the bitter disappointment of liberals when the restored Bourbon monarchy, encouraged by the Catholic hierarchy, rejected the Spanish Constitution of 1812 and opposed both state and religious reform. Since their first publication, Goya's scenes of atrocities, starvation, degradation and humiliation have been described as the "prodigious flowering of rage".[51]

His works from 1814 to 1819 are mostly commissioned portraits, but also include the altarpiece of Santa Justa and Santa Rufina for the Cathedral of Seville, the print series of La Tauromaquia depicting scenes from bullfighting, and probably the etchings of Los Disparates.

Goya is often referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns.[71][72][73] Among the 20th-century painters influenced by Goya are the Spanish masters Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí who drew influence from Los caprichos and the Black Paintings of Goya.[74] In the 21st century, American postmodern painters such as Michael Zansky and Bradley Rubenstein draw inspiration from "The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters" (1796–98) and Goya's Black Paintings. Zanksy's "Giants and Dwarf Series" (1990–2002) of large-scale paintings and wood carvings use imagery from Goya.[75][76]

Goya's influence has extended beyond the visual arts: