Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical philosophy. It is associated with the Institute for Social Research founded at Goethe University Frankfurt in 1923. Formed during the Weimar Republic during the European interwar period, the first generation of the Frankfurt School was composed of intellectuals, academics, and political dissidents dissatisfied with the contemporary socio-economic systems of the 1930s; namely, capitalism, fascism, and communism.

The Frankfurt theorists proposed that existing social theory was unable to explain the turbulent political factionalism and reactionary politics, such as Nazism, of 20th-century liberal capitalist societies. Also critical of Marxism–Leninism as a philosophically inflexible system of social organization, the School's critical-theory research sought alternative paths to social development.

What unites the disparate members of the School is a shared commitment to the project of human emancipation, theoretically pursued by an attempted synthesis of the Marxist tradition, psychoanalysis, and empirical sociological research.[1][2][3][4]

Praxis

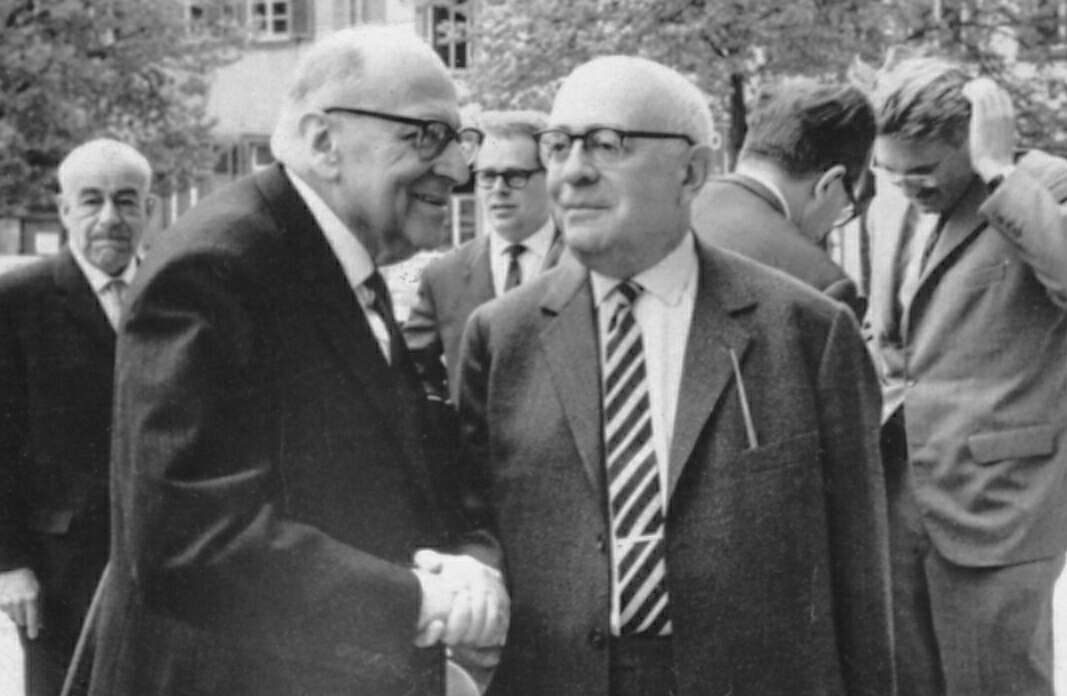

Members of the Frankfurt School were academics and generally avoided (direct) political action or praxis.[36] Max Horkheimer opposed any revolutionary rhetoric in the institute's publications, since it could jeopardize funding from the West German government.[37] Theodor Adorno showed some sympathy to student movements, particularly after the killing of Benno Ohnesorg, but he did not believe street violence had the potential to effect change.[38][39] Angela Davis, a student of Marcuse, recounted advice given to her by Adorno that critical theorists working in the radical movements of the 1960s were, "akin to a media studies scholar deciding to become a radio technician".[37][40]

In The Theory of the Novel (1971), György Lukács criticized the "leading German intelligentsia", including some members of the Frankfurt School (Adorno is named explicitly), as inhabiting the Grand Hotel Abyss, a metaphorical place from which the theorists comfortably analyze the abyss, the world beyond. Lukács described this contradictory situation as follows: They inhabit "a beautiful hotel, equipped with every comfort, on the edge of an abyss, of nothingness, of absurdity. And the daily contemplation of the abyss, between excellent meals or artistic entertainments, can only heighten the enjoyment of the subtle comforts offered."[41][38]

The singular exception to this was Herbert Marcuse, who engaged with the new left in the 1960s and 1970s.[36][38] Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man described the containment of the working class by material consumption and mass media that diverted any possibility of a proletarian revolution. Although Marcuse considered this pessimistic state of affairs to be fait accompli when the book was published in 1964, he was surprised and pleased when almost immediately the civil rights movement intensified and serious opposition to the Vietnam war began. Student activists such as the Students for a Democratic Society in turn took an interest in Marcuse and his works. Formerly an obscure academic émigré, he rapidly became a controversial public intellectual known as the "Guru of the New Left". Marcuse did not aim for narrow, incremental reforms but for the "Great Refusal" of all existing culture and "total revolution" against capitalism. In the democratic protests movements, Marcuse saw agents of change that could supplement the quiescent working class and unite with third-world communist revolutionaries. Marcuse took an active role in the New Left, organizing events with students in the United States and the West German student movement.[36]

Marcuse's relationship with Horkheimer and Adorno was strained by their divergence of opinion about the student movements.[36][39] The Socialist German Students' Union was harshly critical of Adorno for his lack of political engagement and would disrupt his lectures.[39] When a student's room was trashed for refusing to take part in protests, Adorno wrote, "praxis serves as an ideological pretext for exercising moral constraint." Adorno further said it was a manifestation of the authoritarian personality.[38] Adorno's student Hans-Jürgen Krahl was also critical of Adorno's inaction.[39] When in January 1969, Krahl led a group of students to occupy a room, Adorno called the police to remove them, further angering the students.[39] Marcuse criticized Adorno's decision to call the police, writing "I reject the unmediated translation of theory into praxis just as emphatically as you do. But I do believe that there are situations, moments, in which theory is pushed on further by praxis — situations and moments in which theory that is kept separate from praxis becomes untrue to itself".[39]

In the 1970s, perceiving the limitations of the new left, Marcuse de-emphasized the third world and revolutionary violence in favor of a focus on social issues in the United States.[36] He sought to recruit other movements on the political periphery, such as environmentalism and feminism, to a popular front for socialism. During this period, he spoke enthusiastically about women's liberation, seeing in it echoes of his earlier work in Eros and Civilization. Seeing that the revolutionary moment of the 1960s was over, Marcuse advised students to avoid even a suggestion of violence. Instead, he advocated the "long march through the institutions" and recommended educational institutions as a refuge for radicals in the U.S.[36]

Criticism

Psychoanalytic categorization

The historian Christopher Lasch criticized the Frankfurt School for their initial tendency of "automatically" rejecting opposing political criticisms, based upon "psychiatric" grounds: