Fugue

In classical music, a fugue (/fjuːɡ/) is a contrapuntal, polyphonic compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches), which recurs frequently throughout the course of the composition. It is not to be confused with a fuguing tune, which is a style of song popularized by and mostly limited to early American (i.e. shape note or "Sacred Harp") music and West Gallery music. A fugue usually has three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a final entry that contains the return of the subject in the fugue's tonic key. Fugues can also have episodes—parts of the fugue where new material is heard, based on the subject—a stretto, when the fugue's subject "overlaps" itself in different voices, or a recapitulation.[1] A popular compositional technique in the Baroque era, the fugue was fundamental in showing mastery of harmony and tonality as it presented counterpoint.

For other uses, see Fugue (disambiguation).

In the Middle Ages, the term was widely used to denote any works in canonic style; by the Renaissance, it had come to denote specifically imitative works.[2] Since the 17th century,[3] the term fugue has described what is commonly regarded as the most fully developed procedure of imitative counterpoint.[4]

Most fugues open with a short main theme, the subject,[5] which then sounds successively in each voice (after the first voice is finished stating the subject, a second voice repeats the subject at a different pitch, and other voices repeat in the same way); when each voice has completed the subject, the exposition is complete. This is often followed by a connecting passage, or episode, developed from previously heard material; further "entries" of the subject then are heard in related keys. Episodes (if applicable) and entries are usually alternated until the "final entry" of the subject, by which point the music has returned to the opening key, or tonic, which is often followed by closing material, the coda.[6][7][8] In this sense, a fugue is a style of composition, rather than a fixed structure.

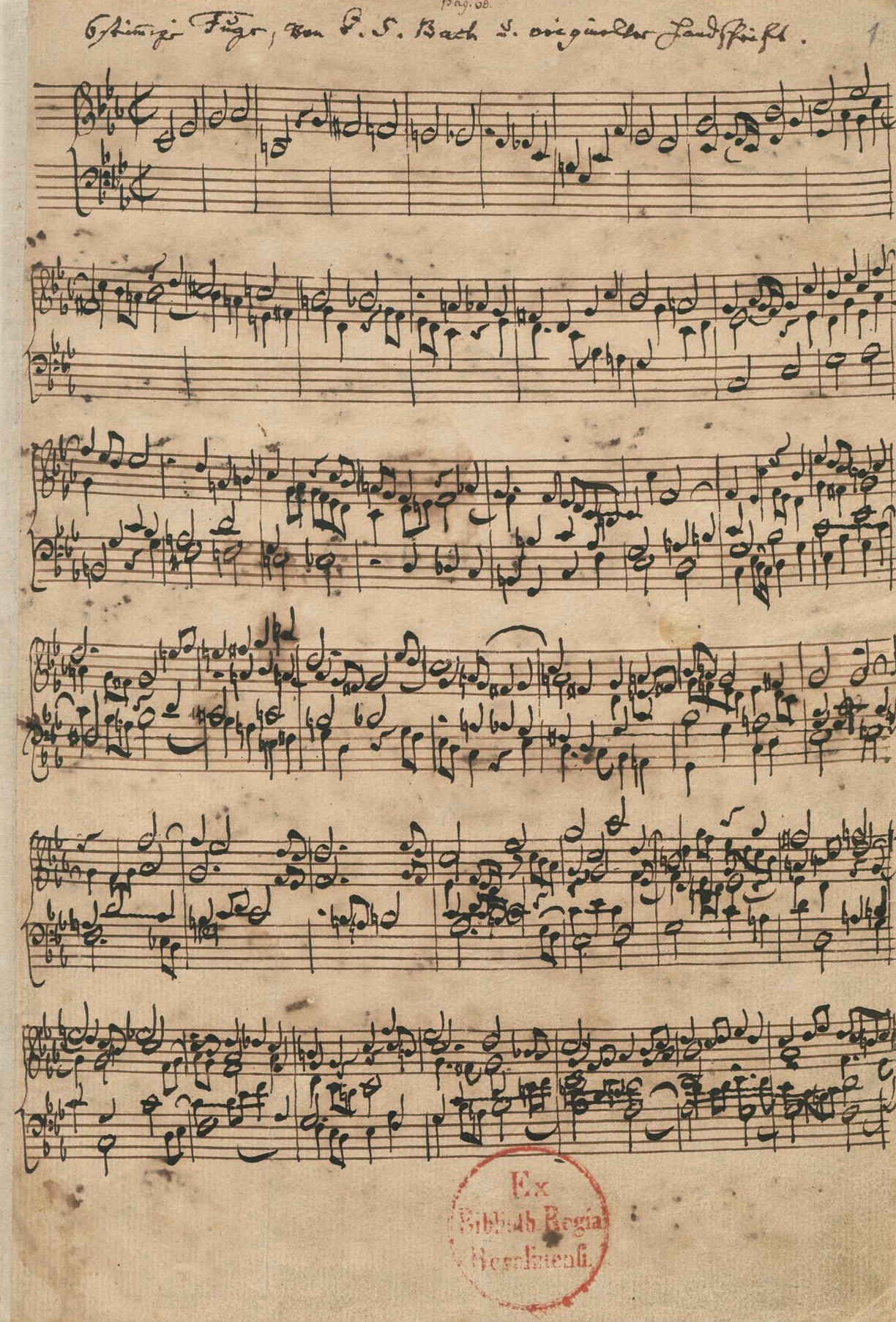

The form evolved during the 18th century from several earlier types of contrapuntal compositions, such as imitative ricercars, capriccios, canzonas, and fantasias.[9] The famous fugue composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) shaped his own works after those of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621), Johann Jakob Froberger (1616–1667), Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643), Dieterich Buxtehude (c. 1637–1707) and others.[9] With the decline of sophisticated styles at the end of the baroque period, the fugue's central role waned, eventually giving way as sonata form and the symphony orchestra rose to a dominant position.[10] Nevertheless, composers continued to write and study fugues for various purposes; they appear in the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)[10] and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827),[10] as well as modern composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) and Paul Hindemith (1895–1963).[11]

Etymology[edit]

The English term fugue originated in the 16th century and is derived from the French word fugue or the Italian fuga. This in turn comes from Latin, also fuga, which is itself related to both fugere ("to flee") and fugare ("to chase").[12] The adjectival form is fugal.[13] Variants include fughetta ("a small fugue") and fugato (a passage in fugal style within another work that is not a fugue).[6]

Types[edit]

Simple fugue[edit]

A simple fugue has only one subject, and does not utilize invertible counterpoint.[33]

Double (triple, quadruple) fugue[edit]

A double fugue has two subjects that are often developed simultaneously. Similarly, a triple fugue has three subjects.[34][35] There are two kinds of double (triple) fugue: (a) a fugue in which the second (third) subject is (are) presented simultaneously with the subject in the exposition (e.g. as in Kyrie Eleison of Mozart's Requiem in D minor or the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582), and (b) a fugue in which all subjects have their own expositions at some point, and they are not combined until later (see for example, the three-subject Fugue No. 14 in F♯ minor from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier Book 2, or more famously, Bach's "St. Anne" Fugue in E♭ major, BWV 552, a triple fugue for organ.)[34][36]

Counter-fugue[edit]

A counter-fugue is a fugue in which the first answer is presented as the subject in inversion (upside down), and the inverted subject continues to feature prominently throughout the fugue.[37] Examples include Contrapunctus V through Contrapunctus VII, from Bach's The Art of Fugue.[38]

Permutation fugue[edit]

Permutation fugue describes a type of composition (or technique of composition) in which elements of fugue and strict canon are combined.[39] Each voice enters in succession with the subject, each entry alternating between tonic and dominant, and each voice, having stated the initial subject, continues by stating two or more themes (or countersubjects), which must be conceived in correct invertible counterpoint. (In other words, the subject and countersubjects must be capable of being played both above and below all the other themes without creating any unacceptable dissonances.) Each voice takes this pattern and states all the subjects/themes in the same order (and repeats the material when all the themes have been stated, sometimes after a rest).

There is usually very little non-structural/thematic material. During the course of a permutation fugue, it is quite uncommon, actually, for every single possible voice-combination (or "permutation") of the themes to be heard. This limitation exists in consequence of sheer proportionality: the more voices in a fugue, the greater the number of possible permutations. In consequence, composers exercise editorial judgment as to the most musical of permutations and processes leading thereto. One example of permutation fugue can be seen in the eighth and final chorus of J.S. Bach's cantata, Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182.

Permutation fugues differ from conventional fugue in that there are no connecting episodes, nor statement of the themes in related keys.[39] So for example, the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582 is not purely a permutation fugue, as it does have episodes between permutation expositions. Invertible counterpoint is essential to permutation fugues but is not found in simple fugues.[40]

Fughetta[edit]

A fughetta is a short fugue that has the same characteristics as a fugue. Often the contrapuntal writing is not strict, and the setting less formal. See for example, variation 24 of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations Op. 120.

History[edit]

Middle Ages and Renaissance[edit]

The term fuga was used as far back as the Middle Ages, but was initially used to refer to any kind of imitative counterpoint, including canons, which are now thought of as distinct from fugues.[41] Prior to the 16th century, fugue was originally a genre.[42] It was not until the 16th century that fugal technique as it is understood today began to be seen in pieces, both instrumental and vocal. Fugal writing is found in works such as fantasias, ricercares and canzonas.

"Fugue" as a theoretical term first occurred in 1330 when Jacobus of Liege wrote about the fuga in his Speculum musicae.[43] The fugue arose from the technique of "imitation", where the same musical material was repeated starting on a different note.

Gioseffo Zarlino, a composer, author, and theorist in the Renaissance, was one of the first to distinguish between the two types of imitative counterpoint: fugues and canons (which he called imitations).[42] Originally, this was to aid improvisation, but by the 1550s, it was considered a technique of composition. The composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525?–1594) wrote masses using modal counterpoint and imitation, and fugal writing became the basis for writing motets as well.[44] Palestrina's imitative motets differed from fugues in that each phrase of the text had a different subject which was introduced and worked out separately, whereas a fugue continued working with the same subject or subjects throughout the entire length of the piece.

Baroque era[edit]

It was in the Baroque period that the writing of fugues became central to composition, in part as a demonstration of compositional expertise. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Johann Jakob Froberger and Dieterich Buxtehude all wrote fugues.[45]

Fugues were incorporated into a variety of musical genres, and are found in most of George Frideric Handel's oratorios. Keyboard suites from this time often conclude with a fugal gigue. Domenico Scarlatti has only a few fugues among his corpus of over 500 harpsichord sonatas. The French overture featured a quick fugal section after a slow introduction. The second movement of a sonata da chiesa, as written by Arcangelo Corelli and others, was usually fugal.

The Baroque period also saw a rise in the importance of music theory. Some fugues during the Baroque period were pieces designed to teach contrapuntal technique to students.[46] The most influential text was Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus Ad Parnassum ("Steps to Parnassus"), which appeared in 1725.[47] This work laid out the terms of "species" of counterpoint, and offered a series of exercises to learn fugue writing.[48] Fux's work was largely based on the practice of Palestrina's modal fugues.[49] Mozart studied from this book, and it remained influential into the nineteenth century. Haydn, for example, taught counterpoint from his own summary of Fux and thought of it as the basis for formal structure.

Bach's most famous fugues are those for the harpsichord in The Well-Tempered Clavier, which many composers and theorists look at as the greatest model of fugue.[50] The Well-Tempered Clavier comprises two volumes written in different times of Bach's life, each comprising 24 prelude and fugue pairs, one for each major and minor key. Bach is also known for his organ fugues, which are usually preceded by a prelude or toccata. The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080, is a collection of fugues (and four canons) on a single theme that is gradually transformed as the cycle progresses. Bach also wrote smaller single fugues and put fugal sections or movements into many of his more general works. J.S. Bach's influence extended forward through his son C.P.E. Bach and through the theorist Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718–1795) whose Abhandlung von der Fuge ("Treatise on the fugue", 1753) was largely based on J.S. Bach's work.

Classical era[edit]

During the Classical era, the fugue was no longer a central or even fully natural mode of musical composition.[51] Nevertheless, both Haydn and Mozart had periods of their careers in which they in some sense "rediscovered" fugal writing and used it frequently in their work.

Discussion[edit]

Musical form or texture[edit]

A widespread view of the fugue is that it is not a musical form but rather a technique of composition.[73]

The Austrian musicologist Erwin Ratz argues that the formal organization of a fugue involves not only the arrangement of its theme and episodes, but also its harmonic structure.[74] In particular, the exposition and coda tend to emphasize the tonic key, whereas the episodes usually explore more distant tonalities. Ratz stressed, however, that this is the core, underlying form ("Urform") of the fugue, from which individual fugues may deviate.

Although certain related keys are more commonly explored in fugal development, the overall structure of a fugue does not limit its harmonic structure. For example, a fugue may not even explore the dominant, one of the most closely related keys to the tonic. Bach's Fugue in B♭ major from Book 1 of the Well Tempered Clavier explores the relative minor, the supertonic and the subdominant. This is unlike later forms such as the sonata, which clearly prescribes which keys are explored (typically the tonic and dominant in an ABA form). Then, many modern fugues dispense with traditional tonal harmonic scaffolding altogether, and either use serial (pitch-oriented) rules, or (as the Kyrie/Christe in György Ligeti's Requiem, Witold Lutosławski works), use panchromatic, or even denser, harmonic spectra.

Perceptions and aesthetics[edit]

The fugue is the most complex of contrapuntal forms. In Ratz's words, "fugal technique significantly burdens the shaping of musical ideas, and it was given only to the greatest geniuses, such as Bach and Beethoven, to breathe life into such an unwieldy form and make it the bearer of the highest thoughts."[75] In presenting Bach's fugues as among the greatest of contrapuntal works, Peter Kivy points out that "counterpoint itself, since time out of mind, has been associated in the thinking of musicians with the profound and the serious"[76] and argues that "there seems to be some rational justification for their doing so."[77]

This is related to the idea that restrictions create freedom for the composer, by directing their efforts. He also points out that fugal writing has its roots in improvisation, and was, during the Renaissance, practiced as an improvisatory art. Writing in 1555, Nicola Vicentino, for example, suggests that: