Gallipoli campaign

The Gallipoli campaign, the Dardanelles campaign, the Defence of Gallipoli or the Battle of Gallipoli (Turkish: Gelibolu Muharebesi, Çanakkale Muharebeleri or Çanakkale Savaşı) was a military campaign in the First World War on the Gallipoli peninsula (now Gelibolu) from 19 February 1915 to 9 January 1916. The Entente powers, Britain, France and the Russian Empire, sought to weaken the Ottoman Empire, one of the Central Powers, by taking control of the Ottoman straits. This would expose the Ottoman capital at Constantinople to bombardment by Entente battleships and cut it off from the Asian part of the empire. With the Ottoman Empire defeated, the Suez Canal would be safe and the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits would be open to Entente supplies to the Black Sea and warm-water ports in Russia.

"Battle of Gallipoli" redirects here. For other uses, see Battle of Gallipoli (disambiguation).

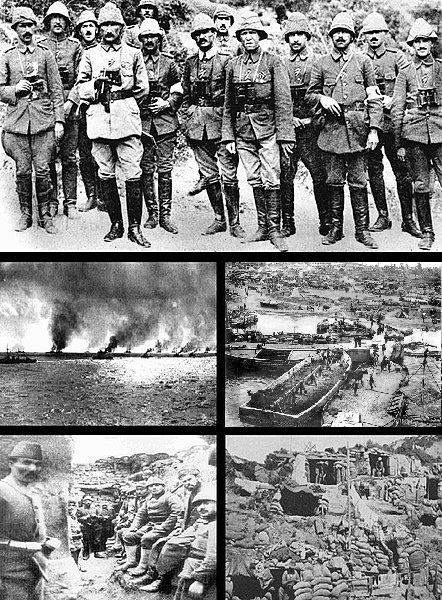

In February 1915 the Entente fleet failed when it tried to force a passage through the Dardanelles. The naval action was followed by an amphibious landing on the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915. In January 1916, after eight months' fighting, with approximately 250,000 casualties on each side, the land campaign was abandoned and the invasion force was withdrawn. It was a costly campaign for the Entente powers and the Ottoman Empire as well as for the sponsors of the expedition, especially the First Lord of the Admiralty (1911–1915), Winston Churchill. The campaign was considered a great Ottoman victory. In Turkey, it is regarded as a defining moment in the history of the state, a final surge in the defence of the motherland as the Ottoman Empire retreated. The struggle formed the basis for the Turkish War of Independence and the declaration of the Republic of Turkey eight years later, with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who rose to prominence as a commander at Gallipoli, as founder and president.

The campaign is often considered to be the beginning of Australian and New Zealand national consciousness. The anniversary of the landings, 25 April, is known as Anzac Day, the most significant commemoration of military casualties and veterans in the two countries, surpassing Remembrance Day (Armistice Day).[12][13][14]

The significance of the Gallipoli campaign is felt strongly in both Australia and New Zealand, despite their being only a portion of the Entente forces; the campaign is regarded in both nations as a "baptism of fire" and had been linked to their emergence as independent states.[279] Approximately 50,000 Australians served at Gallipoli and from 16,000 to 17,000 New Zealanders.[280][281][282][283] It has been argued that the campaign proved significant in the emergence of a unique Australian identity following the war, which has been closely linked to popular conceptualisations of the qualities of the soldiers that fought during the campaign, which became embodied in the notion of an "Anzac spirit".[284]

The landing on 25 April is commemorated every year in both countries as "Anzac Day". The first iteration was celebrated unofficially in 1916, at churches in Melbourne, Brisbane and London, before being officially recognised as a public holiday in all Australian states in 1923.[252] The day also became a national holiday in New Zealand in the 1920s.[285] Organised marches by veterans began in 1925, in the same year a service was held on the beach at Gallipoli; two years later the first official dawn service took place at the Sydney Cenotaph. During the 1980s, it became popular for Australian and New Zealand tourists to visit Gallipoli to attend the dawn service there and since then thousands have attended.[252] Over 10,000 people attended the 75th anniversary along with political leaders from Turkey, New Zealand, Britain and Australia.[286] Dawn services are also held in Australia; in New Zealand, dawn services are the most popular form of observance of this day.[287] Anzac Day remains the most significant commemoration of military casualties and veterans in Australia and New Zealand, surpassing Remembrance Day (Armistice Day).[288]

Along with memorials and monuments established in towns and cities, many streets, public places and buildings were named after aspects of the campaign, especially in Australia and New Zealand.[290] Some examples include Gallipoli Barracks at Enoggera in Queensland,[291] and the Armed Forces Armoury in Corner Brook, Newfoundland which is named the Gallipoli Armouries.[292] Gallipoli also had a significant impact on popular culture, including film, television and song.[293] In 1971, Scottish-born Australian folk singer-songwriter Eric Bogle wrote a song called "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda" which consisted of an account from a young Australian soldier who was maimed during the Gallipoli campaign. The song has been praised for its imagery, evoking the devastation at the Gallipoli landings. It remains widely popular and is considered by some to be an iconic anti-war song.[294][295]

In Turkey, the battle is thought of as a significant event in the state's emergence, although it is primarily remembered for the fighting that took place around the port of Çanakkale, where the Royal Navy was repulsed in March 1915.[296] For the Turks, 18 March has a similar significance as 25 April to Australians and New Zealanders; it is not a public holiday but is commemorated with special ceremonies.[297] The campaign's main significance to the Turkish people lies in the role it played in the emergence of Mustafa Kemal, who became the first president of the Republic of Turkey after the war.[298] "Çanakkale geçilmez" (Çanakkale is impassable) became a common phrase to express the state's pride at repulsing the attack and the song "Çanakkale içinde" (A Ballad for Chanakkale) commemorates the Turkish youth who fell during the battle.[299] Turkish filmmaker Sinan Cetin created a movie called Children of Canakkale.[300]

![The Çanakkale 1915 Bridge on the Dardanelles strait, connecting Europe and Asia, is the longest suspension bridge in the world.[289]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/1915_%C3%87anakkale_Bridge_20220327.jpg/234px-1915_%C3%87anakkale_Bridge_20220327.jpg)