Geography (Ptolemy)

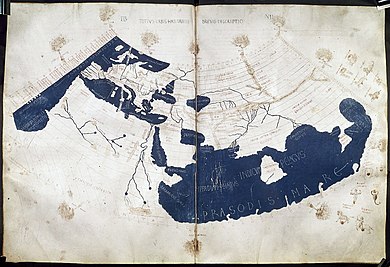

The Geography (Ancient Greek: Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, lit. "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the Geographia and the Cosmographia, is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, compiling the geographical knowledge of the 2nd-century Roman Empire. Originally written by Claudius Ptolemy in Greek at Alexandria around 150 AD, the work was a revision of a now-lost atlas by Marinus of Tyre using additional Roman and Persian gazetteers and new principles.[1] Its translation into Arabic in the 9th century was highly influential on the geographical knowledge and cartographic traditions of the Islamic world. Alongside the works of Islamic scholars – and the commentary containing revised and more accurate data by Alfraganus – Ptolemy's work was subsequently highly influential on Medieval and Renaissance Europe.

History[edit]

Antiquity[edit]

The original treatise by Marinus of Tyre that formed the basis of Ptolemy's Geography has been completely lost. A world map based on Ptolemy was displayed in Augustodunum (Autun, France) in late Roman times.[23] Pappus, writing at Alexandria in the 4th century, produced a commentary on Ptolemy's Geography and used it as the basis of his (now lost) Chorography of the Ecumene.[24] Later imperial writers and mathematicians, however, seem to have restricted themselves to commenting on Ptolemy's text, rather than improving upon it; surviving records actually show decreasing fidelity to real position.[24] Nevertheless, Byzantine scholars continued these geographical traditions throughout the Medieval period.[25]

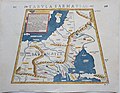

Whereas previous Greco-Roman geographers such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder demonstrated a reluctance to rely on the contemporary accounts of sailors and merchants who plied distant areas of the Indian Ocean, Marinus and Ptolemy betray a much greater receptiveness to incorporating information received from them.[26] For instance, Grant Parker argues that it would be highly implausible for them to have constructed the Bay of Bengal as precisely as they did without the accounts of sailors.[26] When it comes to the account of the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula) and the Magnus Sinus (i.e. Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea), Marinus and Ptolemy relied on the testimony of a Greek sailor named Alexandros, who claimed to have visited a far eastern site called "Cattigara" (most likely Oc Eo, Vietnam, the site of unearthed Antonine-era Roman goods and not far from the region of Jiaozhi in northern Vietnam where ancient Chinese sources claim several Roman embassies first landed in the 2nd and 3rd centuries).[27][28][29][30]

There are two related errors:[51]

This suggests Ptolemy rescaled his longitude data to fit with a figure of 180,000 stadia for the circumference of the Earth, which he described as a "general consensus".[51] Ptolemy rescaled experimentally obtained data in many of his works on geography, astrology, music, and optics.