Gorlice–Tarnów offensive

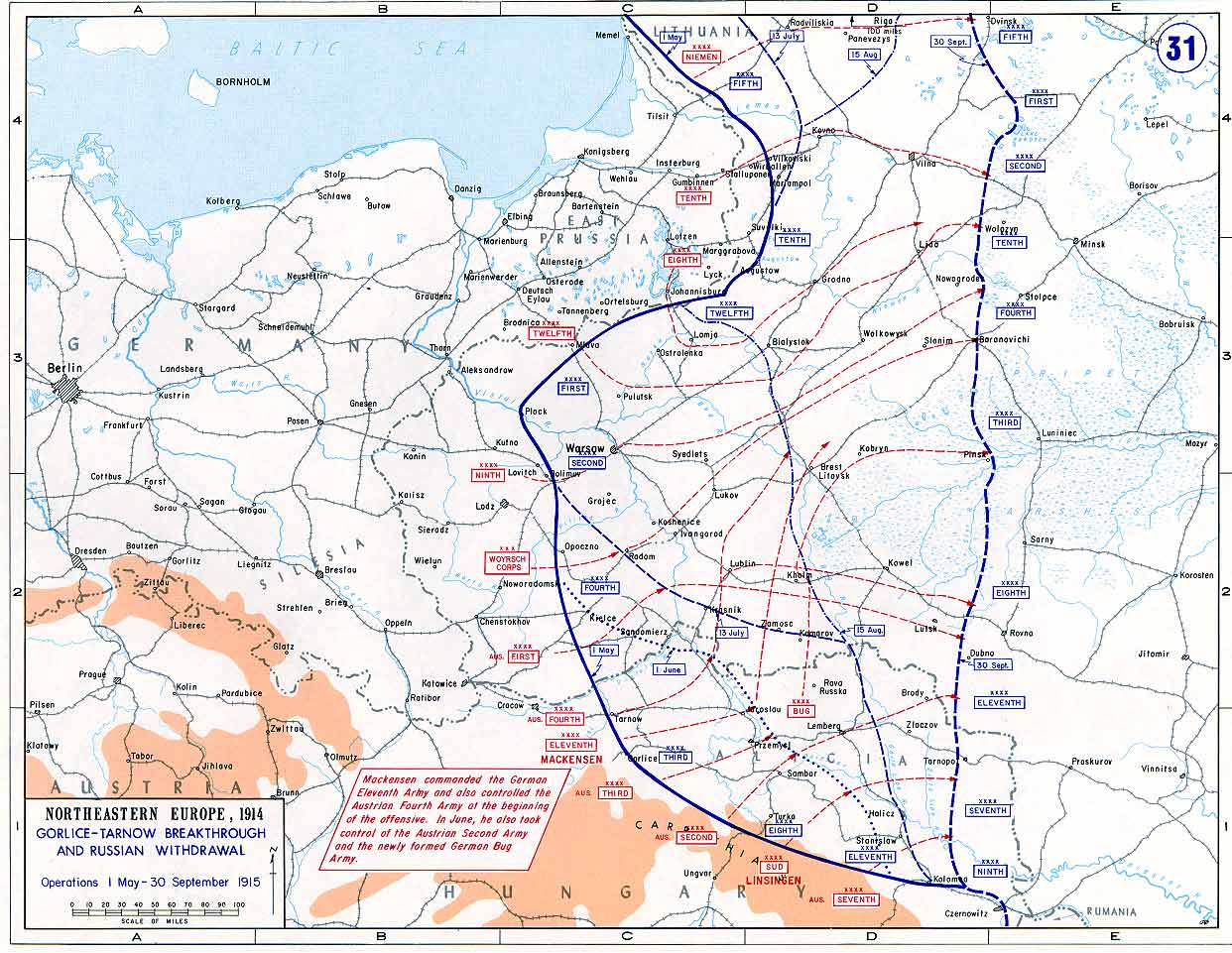

The Gorlice–Tarnów offensive during World War I was initially conceived as a minor German offensive to relieve Russian pressure on the Austro-Hungarians to their south on the Eastern Front, but resulted in the Central Powers' chief offensive effort of 1915, causing the total collapse of the Russian lines and their retreat far into Russia. The continued series of actions lasted the majority of the campaigning season for 1915, starting in early May and only ending due to bad weather in October.

Mackensen viewed securing a breakthrough as the first phase of an operation, which would then lead to a Russian retreat from the Dukla Pass, and their positions north of the Vistula.[11]: 201

Background[edit]

In the early months of war on the Eastern Front, the German Eighth Army conducted a series of almost miraculous actions against the two Russian armies facing them. After surrounding and then destroying the Russian Second Army at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff wheeled their troops to face the Russian First Army at the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, almost destroying them before they reached the protection of their own fortresses as they retreated across the border.[12]

At the same time, the Austro-Hungarian Army launched a series of attacks collectively known as the Battle of Galicia that were initially successful but soon turned into a retreat that did not stop until reaching the Carpathian Mountains in late September. Over the next weeks, Russian troops continued to press forward into the Carpathian passes in the south of Galicia. In fierce winter fighting General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the chief of staff of the Austro-Hungarian Army, attacked the Russians in an attempt to push them back. Both sides suffered appallingly, but the Russians held their line.[13] By this time half of the Austro-Hungarian Army that had entered the war were casualties. Conrad pleaded for additional German reinforcements to hold the passes. German Chief of German Great General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn refused, but in April 1915 Conrad threatened a separate peace if the Germans would not help.[14]

According to Prit Buttar, "...it did seem as if the Russian Army had been gravely weakened by the recent campaigns...both AOK and OHL knew about Russian losses and difficulties with ammunition supply. Therefore, merely reducing the pressure on the k.u.k. Army would not be sufficient; Falkenhayn wished to strike a blow that would permanently diminish the ability of the Russian Army to mount offensives in future..." Falkenhayn wrote Conrad on 13 April, "Your excellency knows that I do not consider advisable a repetition of the attempt to surround the Russian extreme (right) wing. It seems to me just as ill-advised to distribute any more German troops on the Carpathian front for the sole purpose of supporting it. On the other hand, I should like to submit the following plan of operations for your consideration...An army of at least eight German divisions will be got ready with strong artillery here in the west, and entrained for Muczyn-Grybów-Bochnia, to advance from about the line Gorlice-Gromnik in the general direction of Sanok."

Conrad met Falkenhayn in Berlin on 14 April, where final details of Falkenhayn's plan were agreed upon, and two days later orders were issued for the creation of the Eleventh Army. According to Buttar, the Eleventh Army would consist of the "...Guards Corps reinforced by the 119th Division, XLI Reserve Corps reinforced by 11th Bavarian Infantry Division, and X Corps. Archduke Joseph Ferdinand's Fourth Army would be subordinated to the new German army. Eventually, 119th Infantry Division and 11th Bavarian Infantry Division were grouped together in Korps Kneussl, and additional troops in the form of the Austro-Hungarian VI Corps were added to the Eleventh Army." Buttar goes on to state, "Impressed by the resilience of German troops on the Western Front when the French attacked in late 1914 and again in early 1915, Falkenhayn had adopted the proposal of Oberst Ernst von Wrisberg...and ordered some divisions to give up one of their four regiments and to reduce their artillery batteries from six guns to four." These forces were used to create new divisions for the new Eleventh Army.[11]

Conrad had to bow to Falkenhayn's conditions. The joint attack would be by an Austro-German Army Group commanded by a German, whose orders from Falkenhayn would be transmitted via the Austro-Hungarian command. The Group would contain the Austro-Hungarian Fourth Army (eight infantry and one cavalry divisions) under Archduke Joseph Ferdinand, an experienced soldier. The Germans formed a new Eleventh Army made up of eight divisions, trained in assault tactics in the west. They were brought east on 500 trains.[15][11]: 179

The Eleventh Army was led by the former commander of the German Ninth Army, General August von Mackensen, with Colonel Hans von Seeckt as chief of staff. They would be opposed by the Russian Third Army with eighteen and a half infantry and five and a half cavalry divisions, under General D. R. Radko-Dmitriev. Mackensen was provided with a strong train of heavy artillery commanded by Generalmajor Alfred Ziethen, which included the huge German and Austro-Hungarian mortars that had crushed French and Belgian fortresses. Airplanes were provided to direct artillery fire, which was especially important since ammunition was short on both sides: only 30,000 shells could be stockpiled for the attack.[16] Another significant plus was the German field telephone service, which advanced with the attackers, thereby enabling front-line observers to direct artillery fire.[17] To increase their mobility on the poor roads, each German division was provided with 200 light Austro-Hungarian wagons with drivers.[18]

The German Eleventh Army was ready to start artillery operations by 1 May, with the Korps Kneussl deployed southwest of Gorlice, with the XLI Reserve Corps led by Hermann von François, Austro-Hungarian VI Corps led by Arthur Arz, and the Guards Corps led by Karl von Plettenberg, deployed south to north, while the X Corps was held in reserve. Joseph Ferdinand's Fourth Army was deployed north of the Germans at Gromnik. The Russian Third Army was deployed with the X Corps led by Nikolai Protopopov, XXI Corps led by Jakov Shchkinsky, and IX Corps led by Dmitry Shcherbachev, deployed south to north.[11]: 179–180, 186–187

Casualties and losses[edit]

The battles on the Bug and Zlota Lipa Rivers ended the Gorlice–Tarnów offensive, during which the armies of the Central Powers managed to inflict the largest defeat on the troops of the Russian Empire. The operation, which lasted 70 days, in terms of the number of troops involved (taking into account the replenishment of combat and non-combat сasualties – 4.5 million men on both sides), in terms of сasualties of the opponents (on both sides more than 1.5 million men), in terms of trophies, became the largest during the First World War.[26]

Heavy сasualties in the May battles forced the Russian armies to retreat from Galicia in early June 1915, and so hastily that the fortified positions prepared in the rear remained abandoned. The low stability of the troops of the Russian 8th Army, which left Lvov on June 22, became the reason for sharp reprimands from the front headquarters. In the Russian armies south of the Pilica River, 26 infantry divisions were transferred and put into battle in 70 days, two more guard divisions remained in reserve. But for the armies of the Central Powers, the victory came at a high price. The arriving reserves (6.5 divisions) brought into action during the offensive were fully utilized by the beginning of July. Although the Russian troops at certain moments of the battles lacked artillery shells (while the consumption of shells was the highest since the beginning of the war), they were well equipped with rifle cartridges and retained an advantage in the number of machine guns. Skillfully directed fire from hand weapons was very effective, and massive frontal assaults cost the victorious troops dearly, which was reflected in the gradual narrowing of the breakthrough front.[27]

The available official information about the trophies of the warring parties allows to clarify the number of those who died in the operation. This number is made up of those killed and missing, not taken prisoner. The Austria-Hungary's Army Higher Command (AOK) and the German Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East (Ober Ost) announced the capture in May – early July 1915 in Galicia, Bukovina and the Kingdom of Poland 3 generals, 1,354 officers and 445,622 soldiers of the Russian army, 350 guns, 983 machine guns.[28] The Russian side officially announced the capture in May-June 1915 of 100,476 prisoners (of which 1,366 officers), 68 guns, 3 mortars and 218 machine guns of the Central Powers.[29]

Based on these data, it can be assumed that 170,628 men died on the part of the Russian troops in the operation, and 140,420 men died on the part of the Central Powers. After the retreat of the Russian troops from Galicia, only within the military districts of Kraków, Lvov (Lemberg) and Przemyśl, 566,833 soldiers of the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian armies who had died since the beginning of the war were officially buried. At the same time, the foundation was laid for the creation of a network of war memorials.[30]

Central Powers (arrayed north to south):

Austro-Hungarian 4th Army (Austro-Hungarian units unless otherwise indicated):

German 11th Army (German units unless otherwise indicated):

Austro-Hungarian 3rd Army,

Russian 3rd Army (north to south):

Behind the Russian front lines:

Scattered across the rear of 3rd Army:

Army Reserve: