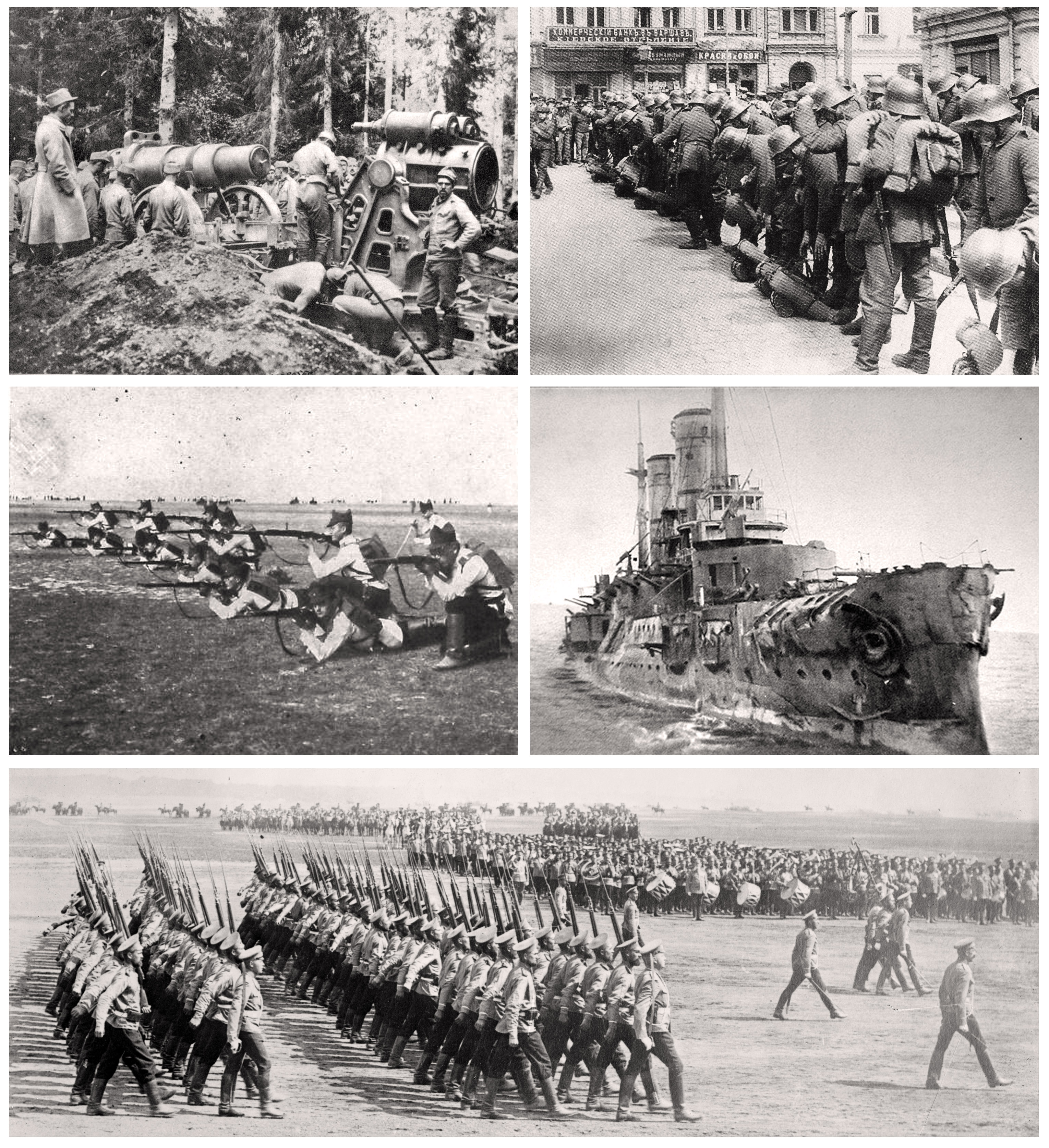

Eastern Front (World War I)

The Eastern Front or Eastern Theater of World War I (German: Ostfront; Romanian: Frontul de răsărit; Russian: Восточный фронт, romanized: Vostochny front) was a theater of operations that encompassed at its greatest extent the entire frontier between Russia and Romania on one side and Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, and Germany on the other. It ranged from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south, involved most of Eastern Europe, and stretched deep into Central Europe. The term contrasts with the Western Front, which was being fought in Belgium and France.

During 1910, Russian General Yuri Danilov developed "Plan 19" under which four armies would invade East Prussia. This plan was criticised as Austria-Hungary could be a greater threat than the German Empire. So instead of four armies invading East Prussia, the Russians planned to send two armies to East Prussia, and two armies to defend against Austro-Hungarian forces invading from Galicia. In the opening months of the war, the Imperial Russian Army attempted an invasion of eastern Prussia in the Northwestern theater, only to be beaten back by Germany after some initial success. At the same time, in the south, they successfully invaded Galicia, defeating the Austro-Hungarian forces there.[22] In Russian Poland, the Germans failed to take Warsaw. But by 1915, the German and Austro-Hungarian forces were on the advance, dealing the Russians heavy casualties in Galicia and in Poland, forcing them to retreat. Grand Duke Nicholas was sacked from his position as the commander-in-chief and replaced by Tsar Nicholas himself.[23] Several offensives against the Germans in 1916 failed, including the Lake Naroch Offensive and the Baranovichi Offensive. However, General Aleksei Brusilov oversaw a highly successful operation against Austria-Hungary that became known as the Brusilov offensive, which saw the Russian Army make large gains.[24][25][26] Being the largest and most lethal offensive of World War I, the effects of the Brusilov offensive were far reaching. It helped to relieve the German pressure during the Battle of Verdun, while also helping to relieve the Austro-Hungarian pressure on the Italians. As a result, the Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces were fatally weakened, and finally Romania decided to enter the war on the side of the Allies. However, the Russian human and material losses also greatly contributed to the Russian Revolutions.[27]

Romania entered the war in August 1916. The Allied Powers promised the region of Transylvania (which was part of Austria-Hungary) in return for Romanian support. The Romanian Army invaded Transylvania and had initial successes, but was forced to stop and was pushed back by the Germans and Austro-Hungarians when Bulgaria attacked them from the south. Meanwhile, a revolution occurred in Russia in March 1917 (one of the causes being the hardships of the war). Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate and a Russian Provisional Government was founded, with Georgy Lvov as its first leader, who was eventually replaced by Alexander Kerensky.

The newly formed Russian Republic continued to fight the war alongside Romania and the rest of the Entente in desultory fashion. It was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in November 1917. Following the Armistice of Focșani between Romania and the Central Powers, Romania also signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers on 7 May 1918, however it was canceled by Romania on 10 November 1918. The new government established by the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers in March 1918, taking it out of the war; leading to a Central Powers victory on the Eastern Front and Russian defeat in World War I.

Propaganda[edit]

Propaganda was a key component of the culture of World War I. It was often shown through state-controlled media, and helped to bolster nationalism and patriotism within countries. On the Eastern Front, propaganda took many forms such as opera, film, spy fiction, theater, spectacle, war novels and graphic art. Across the Eastern Front the amount of propaganda used in each country varied from state to state. Propaganda took many forms within each country and was distributed by many different groups. Most commonly the state produced propaganda, but other groups, such as anti-war organizations, also generated propaganda.[28]

Armistice[edit]

With the end of major combat on the Eastern Front, the Germans were able to transfer substantial forces to the west in order to mount an offensive in France in the spring of 1918.

This offensive on the Western Front failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough, and the arrival of more and more American units in Europe was sufficient to offset the German advantage. Even after the Russian collapse, about a million German soldiers remained tied up in the east until the end of the war, attempting to run a short-lived addition to the German Empire in Europe. In the end, the Central Powers had to relinquish all of their captured lands on the eastern front, with Germany even being forced to cede territory they held before the war, under various treaties (such as the Treaty of Versailles) signed after the armistice in 1918. Although the Allied Powers' victory led to the Central Powers being forced to cancel the treaty signed with Russia, the victors were at the time intervening in the Russian Civil War, causing bad relations between Russia and the Allied Powers.

Prisoners of war in Russia[edit]

During World War I, approximately 200,000 German soldiers and 2.5 million soldiers from the Austro-Hungarian army entered Russian captivity. During the 1914 Russian campaign the Russians began taking thousands of Austrian prisoners. As a result, the Russian authorities made emergency facilities in Kiev, Penza, Kazan, and later Turkestan to hold the Austrian prisoners of war. As the war continued Russia began to detain soldiers from Germany as well as a growing number from the Austro-Hungarian army. The Tsarist state saw the large population of POWs as a workforce that could benefit the war economy in Russia. Many POWs were employed as farm laborers and miners in Donbas and Krivoi Rog. However, the majority of POWs were employed as laborers constructing canals and building railroads. The living and working environments for these POWs was bleak. There was a shortage of food, clean drinking water and proper medical care. During the summer months malaria was a major problem, and the malnutrition among the POWs led to many cases of scurvy. While working on the Murmansk rail building project over 25,000 POWs died. Information about the bleak conditions of the labor camps reached the German and Austro-Hungarian governments. They began to complain about the treatment of POWs. The Tsarist authorities initially refused to acknowledge the German and Habsburg governments. They rejected their claims because Russian POWs were working on railway construction in Serbia. However, they slowly agreed to stop using prison labor.[100] Life in the camps was extremely rough for the men who resided in them. The Tsarist government could not provide adequate supplies for the men living in their POW camps. The Russian government's inability to supply the POWs in their camps with supplies was due to inadequate resources and bureaucratic rivalries. However, the conditions in the POW camps varied; some were more bearable than others.[100]

Disease on the Eastern Front[edit]

Disease played a critical role in the loss of life on the Eastern Front. In the East, disease accounted for approximately four times the number of deaths caused by direct combat, in contrast to the three to one ratio in the West.[101] Malaria, cholera, and dysentery contributed to the epidemiological crisis on the Eastern Front; however, typhus fever, transmitted by pathogenic lice and previously unknown to German medical officers before the outbreak of the war, was the most deadly. There was a direct correlation between the environmental conditions of the East and the prevalence of disease. With cities excessively crowded by refugees fleeing their native countries, unsanitary medical conditions created a suitable environment for diseases to spread. Primitive hygienic conditions, along with general lack of knowledge about proper medical care was evident in the German-occupied Ober Ost.[102]

Ultimately, a large scale sanitation program was put into effect. This program, named Sanititätswesen (Medical Affairs), was responsible for ensuring proper hygienic procedures were being carried out in Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. Quarantine centers were built, and diseased neighbourhoods were isolated from the rest of the population. Delousing stations were prevalent in the countryside and in cities to prevent the spread of typhus fever, with mass numbers of natives being forced to take part in this process at military bathhouses. A "sanitary police" was also introduced to confirm the cleanliness of homes, and any home deemed unfit would be boarded up with a warning sign.[102] Dogs and cats were also killed for fear of possible infection.

To avoid the spread of disease, prostitution became regulated. Prostitutes were required to register for a permit, and authorities demanded mandatory medical examinations for all prostitutes, estimating that seventy percent of prostitutes carried a venereal disease.[102] Military brothels were introduced to combat disease; the city of Kowno emphasized proper educational use of contraceptives such as condoms, encouraged proper cleansing of the genital area after intercourse, and gave instructions on treatment in the case of infection.[102]