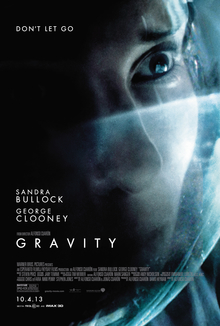

Gravity (2013 film)

Gravity is a 2013 science fiction thriller film directed by Alfonso Cuarón, who also co-wrote, co-edited, and produced the film. It stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as American astronauts who attempt to return to Earth after the destruction of their Space Shuttle in orbit.

Gravity

- Alfonso Cuarón

- Jonás Cuarón

- Alfonso Cuarón

- David Heyman

- Alfonso Cuarón

- Mark Sanger

- August 28, 2013 (Venice)

- October 4, 2013 (United States)

- November 7, 2013 (United Kingdom)

91 minutes[1]

- United Kingdom

- United States[2]

English

$723.2 million[5]

Cuarón wrote the screenplay with his son Jonás and attempted to develop the film at Universal Pictures. Later, the distribution rights were acquired by Warner Bros. Pictures. David Heyman, who previously worked with Cuarón on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004), produced the film with him. Gravity was produced entirely in the United Kingdom, where British visual effects company Framestore spent more than three years creating most of the film's visual effects, which involve over 80 of its 91 minutes.

Gravity opened the 70th Venice International Film Festival on August 28, 2013, and had its North American premiere three days later at the Telluride Film Festival. Upon its release, Gravity was met with widespread critical acclaim, with high praise for its direction, visuals, cinematography, acting, and score, though some criticized its dialogue. Considered one of the best films of 2013, it appeared on numerous critics' year-end lists, and was selected by the American Film Institute in their annual Movies of the Year list.[6] The film became the eighth highest-grossing film of the year with a worldwide gross of over $723 million, against a production budget of around $100 million.

Gravity received a leading 10 nominations at the 86th Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actress (for Bullock), and won a leading 7 awards, including Best Director (for Cuarón). At the 67th British Academy Film Awards, the film received a leading 11 nominations, including Best Film and Best Actress in a Leading Role (for Bullock), and won a leading 6 awards, including Outstanding British Film and Best Director (for Cuarón). It also received 4 nominations at the 71st Golden Globe Awards, including Best Motion Picture – Drama and Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama (for Bullock), with Cuarón winning Best Director. At the 19th Critics' Choice Awards, the film received 10 nominations, including Best Picture and Best Actress (for Bullock), and won a leading 7 awards, including Best Sci-Fi/Horror Movie, Best Director (for Cuarón) and Best Actress in an Action Movie (for Bullock). Bullock also received a nomination for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role, while the film won the 2013 Ray Bradbury Award,[7] and the 2014 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation. Since its release, it has been cited as among the best films of the 2010s, the 21st century.[a]

Plot[edit]

The Space Shuttle Explorer, commanded by veteran astronaut Matthew "Matt" Kowalski, is in Earth orbit to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Dr. Ryan Stone is aboard on her first space mission, to perform a set of hardware upgrades on the Hubble. During a spacewalk, Mission Control in Houston warns Explorer's crew about a rapidly expanding cloud of space debris accidentally caused by the Russians having shot down a presumed defunct spy satellite (see Kessler syndrome) and orders the crew to return to Earth immediately. Communication with Mission Control is lost shortly after as more communication satellites are disabled by debris.

Debris strikes the Explorer and Hubble, tearing Stone from the shuttle and leaving her tumbling through space. Kowalski, using a Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), rescues Stone and they return to the Explorer, discovering that the Shuttle has suffered catastrophic damage and the rest of the crew are dead. Stone and Kowalski decide to use the MMU to reach the International Space Station (ISS), which is in orbit about 1,450 km (900 mi) away, Kowalski estimating that they have 90 minutes before the debris field completes an orbit and threatens them again.

On their way to the ISS, the two discuss Stone's home life and her daughter, who died young in an accident. As they approach the station, they see that the ISS's crew has evacuated using one of its two Soyuz spacecraft, the remaining Soyuz spacecraft exhibiting damage with its parachute having been deployed in space rendering it unable to return to Earth. Kowalski suggests using it to travel to the nearby Tiangong space station,[N 1] 100 km (60 mi) away, in order to board the Shenzhou spacecraft to return safely to Earth. Out of air and fuel, the two try to grab onto the ISS; the duo's tether snags on one of the station's solar panels. Stone's leg gets entangled in the Soyuz's parachute cords and she grabs a strap on Kowalski's suit, but it soon becomes clear that the cords will not support them both. Despite Stone's protests, Kowalski detaches himself from the tether to save her from drifting away with him. Stone is pulled back towards the ISS, while Kowalski floats away.

Stone enters the space station via the airlock of the Pirs module. She cannot re-establish communication with Kowalski or Earth, and concludes that she is now the sole survivor. Inside the station, a fire breaks out, forcing her to rush to the Soyuz. As she maneuvers the Soyuz away from the ISS, the tangled parachute tethers snag, preventing the spacecraft from leaving; Stone performs a spacewalk to cut the cables, succeeding just as the debris field returns, destroying the station. Stone angles the Soyuz towards Tiangong, but soon discovers that the Soyuz's engine has no fuel.

After an attempt at radio communication with an Inuit on Earth, Stone resigns herself to her fate and shuts off the cabin's oxygen supply to commit suicide. As she begins to lose consciousness, she experiences a hallucination of Kowalski entering the capsule and telling her to rig the Soyuz's soft landing rockets to propel the capsule towards Tiangong. Stone regains the will to go on, restoring the spacecraft's oxygen flow and rigging the landing rockets to propel the capsule towards Tiangong.

Unable to dock with Tiangong, Stone ejects herself from the Soyuz and uses a fire extinguisher as a makeshift thruster to travel to the rapidly deorbiting Tiangong. Stone manages to enter Tiangong's Shenzhou capsule just as the station enters the upper atmosphere, undocking the capsule just in time.

The Shenzhou capsule re-enters the atmosphere successfully, despite damage during its descent, and lands in a lake. Radio communication from Houston informs Stone that she has been tracked on radar and that rescue crews are on their way. Stone opens the hatch but is unable to exit due to water rushing in. She takes a deep breath and holds it until the capsule sinks, allowing her to swim through the hatch. She sheds her Sokol space suit that is weighing her down, and crawls onto the beach before standing up triumphantly and walking away.

Themes[edit]

Although Gravity is often considered to be a science fiction film,[28] Cuarón told the BBC that he does not consider it such, rather seeing it as "a drama of a woman in space".[29] According to him, the main theme of the film was "adversity"[20] and he uses the debris as a metaphor for this.[18]

Despite being set in space, the film uses motifs from shipwreck and wilderness survival stories about psychological change and resilience in the aftermath of a catastrophe.[30][31][32][33] Cuarón uses the Stone character to illustrate clarity of mind, persistence, training, and improvisation in the face of isolation and the consequences of a relentless Murphy's law.[28] The film incorporates spiritual or existential themes, in the facts of Stone's daughter's accidental and meaningless death, and in the necessity of summoning the will to survive in the face of overwhelming odds, without future certainties, and with the impossibility of rescue from personal dissolution without finding this willpower.[31] Calamities occur but only the surviving astronauts see them.[34]

The impact of scenes is heightened by alternating between objective and subjective perspectives, the warm face of the Earth and the depths of dark space, the chaos and unpredictability of the debris field, and silence in the vacuum of space with the background score giving the desired effect.[33][35] The film uses very long, uninterrupted shots throughout to draw the audience into the action, but contrasts these with claustrophobic shots within space suits and capsules.[31][36]

Human evolution and the resilience of life may also be seen as key themes of Gravity.[21][30][37][38] The film opens with the exploration of space—the vanguard of human civilization—and ends with an allegory of the dawn of mankind when Ryan Stone fights her way out of the water after the crash-landing, passing a frog, grabs the soil, and slowly regains her capacity to stand upright and walk. Director Cuarón said, "She's in these murky waters almost like an amniotic fluid or a primordial soup, in which you see amphibians swimming. She crawls out of the water, not unlike early creatures in evolution. And then she goes on all fours. And after going on all fours she's a bit curved until she is completely erect. It was the evolution of life in one, quick shot".[38] Earlier imagery depicting the formation of life includes a scene after Stone enters the space station airlock, and rests in an embryonic position, surrounded by a rope strongly resembling an umbilical cord. The film also suggests themes of humanity's ubiquitous strategy of existential resilience; that, across cultures, individuals must postulate meaning, beyond material existence, wherever none can be perceived.

Some commentators have noted possible religious themes in the film.[39][40][41][42] For instance, Robert Barron in The Catholic Register summarizes the tension between Gravity's technology and religious symbolism. He said, "The technology which this film legitimately celebrates ... can't save us, and it can't provide the means by which we establish real contact with each other. The Ganges in the sun, the Saint Christopher icon, the statue of Budai, and above all, a visit from a denizen of heaven, signal that there is a dimension of reality that lies beyond what technology can master or access ... the reality of God".[42]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

As a child, Alfonso Cuarón had an affinity for space programs, dreamed of becoming an astronaut, and would watch live Moon landings on television.[20] He was 7 years old when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon in 1969 and was profoundly influenced by Neil Armstrong. At that time, his grandmother bought a new television in order to be able to see the Moon landing.[43] He watched space films, such as A Trip to the Moon (1902), and was further drawn to films featuring the technology of space exploration and trying to honor the laws of physics, such as Marooned (1969) and Woman in the Moon (1929).[18]

In 2008, funding ran out on a project entitled A Boy and His Shoe written by Cuarón and his son Jonás. They wrote a first draft of what would become Gravity in three weeks. After they finished the screenplay, Cuarón attempted to develop his project at Universal Pictures, where it stayed in development hell.[44] When co-chairmen Marc Shmuger and David Linde were ousted from Universal in 2009, Cuarón asked for the project to be released, and then Warner Bros Pictures chief Jeff Robinov stepped in. After the rights to the project were sold, it began development at Warner Bros. Three years later, when the movie was still unfinished, Robinov was let go.[17][45][46]

In 2014, author Tess Gerritsen filed a lawsuit against Warner Bros. for breach of contract, alleging that the film Gravity is an adaptation of her 1999 novel of the same name.[47] The suit was dismissed twice in 2015.[48][49]

Writing[edit]

Cuarón co-wrote the screenplay with his son Jonás.[18] However, Cuarón never intended to make a space film. Before conceiving the story, he started out with a theme: adversity. He would discuss with Jonás survival scenarios in hostile, isolated locations, such as the desert (Jonás wrote a desert film, Desierto, which was released in 2015).[20] Finally, he decided to take it to an extreme place where there's nothing: "I had this image of an astronaut spinning into space away from human communication. The metaphor was already so obvious."[20]

Steven Price composed the incidental music for Gravity. In early September 2013, a 23-minute preview of the soundtrack was released online.[73] A soundtrack album was released digitally on September 17, 2013, and in physical formats on October 1, 2013, by WaterTower Music.[74] Songs featured in the film include:[75]

In most of the film's official trailers, Spiegel im Spiegel, written by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt in 1978, was used.[77]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Gravity emerged as one of the most successful sci-fi films of all time, and the biggest box office hit of both Sandra Bullock and George Clooney's careers.[85] It became the highest-grossing feature film in October history, surpassing the animated Puss in Boots[86] and holding the record until 2019's Joker.[87] Bullock's previous highest-grossing film was Speed ($350.2 million) while Clooney's benchmark was Ocean's Eleven ($450.6 million).[85]

Preliminary reports predicted the film would open with around $40 million in the US and Canada.[88][89] The film earned $1.4 million from its Thursday night showings,[90] and reached $17.5 million on Friday.[91] Gravity topped the box office and broke the record held by Paranormal Activity 3 (2011) as the highest-earning October and autumn openings, grossing $55.8 million from 3,575 theaters.[92] The film also surpassed Batman & Robin (1997) for having Clooney's highest opening weekend and The Heat for having Bullock's highest opening weekend respectively.[93] 80 percent of the film's opening weekend gross came from its 3D showings, which grossed $44.2 million from 3,150 theaters. $11.2 million—20 percent of the receipts—came from IMAX 3D showings, the highest percentage for a film opening of more than $50 million.[94] The film stayed at number one at the box office during its second and third weekends.[95][96] IMAX alone generated $34.7 million from 323 theaters, a record for IMAX opening in October.[3]

Gravity earned $27.4 million in its opening weekend overseas from 27 countries with $2.8 million from roughly 4,763 screens. Warner Bros. said the 3D showing "exceeded all expectations" and generated 70 percent of the opening grosses.[3] In China, its second largest market, the film opened on November 19, 2013, and faced competition with The Hunger Games: Catching Fire which opened on November 21, 2013. At the end of the weekend Gravity emerged victorious, generating $35.76 million in six days.[97] It opened at number one in the United Kingdom, taking £6.23 million over the first weekend of release,[98] and remained there for the second week.[99] The film's high notable openings were in Russia and the CIS ($8.1 million), Germany ($3.8 million), Australia ($3.2 million), Italy ($2.6 million) and Spain ($2.3 million).[3] The film's largest markets outside North America were China ($71.2 million),[100] the United Kingdom ($47 million) and France ($38.2 million).[101] By February 17, 2014, the film had grossed $700 million worldwide.[102] Gravity grossed $274,092,705 in North America and $449,100,000 in other countries, making a worldwide gross of $723,192,705—making it the eighth-highest-grossing film of 2013.[5] Calculating in all expenses, Deadline Hollywood estimated that the film made a profit of $209.2 million.[103]

According to the tracking site Excipio, Gravity was one of the most copyright-infringed films of 2014 with over 29.3 million downloads via torrent sites.[104]