Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Greek: εἰκών, eikṓn, 'figure, icon' + κλάω, kláō, 'to break')[i] is the social belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments, most frequently for religious or political reasons. People who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, a term that has come to be figuratively applied to any individual who challenges "cherished beliefs or venerated institutions on the grounds that they are erroneous or pernicious."[1]

For the absence of representations of the natural world or certain religious figures, see Aniconism.

Conversely, one who reveres or venerates religious images is called (by iconoclasts) an iconolater; in a Byzantine context, such a person is called an iconodule or iconophile.[2] Iconoclasm does not generally encompass the destruction of the images of a specific ruler after his or her death or overthrow, a practice better known as damnatio memoriae.

While iconoclasm may be carried out by adherents of a different religion, it is more commonly the result of sectarian disputes between factions of the same religion. The term originates from the Byzantine Iconoclasm, the struggles between proponents and opponents of religious icons in the Byzantine Empire from 726 to 842 AD. Degrees of iconoclasm vary greatly among religions and their branches, but are strongest in religions which oppose idolatry, including the Abrahamic religions.[3] Outside of the religious context, iconoclasm can refer to movements for widespread destruction in symbols of an ideology or cause, such as the destruction of monarchist symbols during the French Revolution.

Calvinist iconoclasm during the Reformation

16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[35][36]

Iconoclasm during the

Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[72] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[73][74]

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple. The temple was destroyed on the orders of Muslim Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[68]

Rani Ki Vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[68]

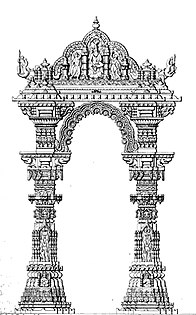

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[75]

There have been several cases of removing symbols of past rulers in 's history. Many Hospitaller coats of arms on buildings were defaced during the French occupation of Malta in 1798–1800; a few of these were subsequently replaced by British coats of arms in the early 19th century.[121] Some British symbols were also removed by the government after Malta became a republic in 1974. These include royal cyphers being ground off from post boxes,[122] and British coats of arms such as that on the Main Guard building being temporarily obscured (but not destroyed).[123]

Malta

With the entry of the to the First World War, the Ottoman Army destroyed the Russian victory monument erected in San Stefano (the modern Yeşilköy quarter of Istanbul, Turkey) to commemorate the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The demolition was filmed by former army officer Fuat Uzkınay, producing Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı—the oldest known Turkish-made film.

Ottoman Empire

In the late 18th century, known as the sans-culottes sacked Brussels' Grand-Place, destroying statues of nobility and symbols of Christianity.[124][125] In the 19th century, the place was renovated and many new statues added. In 1911, a marble commemoration for the Spanish freethinker and educator Francisco Ferrer, executed two years earlier and widely considered a martyr, was erected in the Grand-Place. The statue depicted a nude man holding the Torch of Enlightenment. The Imperial German military, which occupied Belgium during the First World War, disliked the monument and destroyed it in 1915. It was restored in 1926 by the International Free Thought Movement.[126]

French revolutionaries

In 1942, the pro-Nazi took down and melted Clothilde Roch's statue of the 16th-century dissident intellectual Michael Servetus, who had been burned at the stake in Geneva at the instigation of Calvin. The Vichy authorities disliked the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience. In 1960, having found the original molds, the municipality of Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.[127]

Vichy Government of France

A sculpture of the head of Spanish intellectual by Victorio Macho was installed in the City Hall of Bilbao, Spain. It was withdrawn in 1936 when Unamuno showed temporary support for the Nationalist side. During the Spanish Civil War, it was thrown into the estuary. It was later recovered. In 1984 the head was installed in Plaza Unamuno. In 1999, it was again thrown into the estuary after a political meeting of Euskal Herritarrok. It was substituted by a copy in 2000 after the original was located in the water.[128][129][130]

Miguel de Unamuno

The and the regime of Saddam Hussein symbolically ended with the Firdos Square statue destruction, a U.S. military-staged event on 9 April 2003 where a prominent statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down. Subsequently, statues and murals of Saddam Hussein all over Iraq were destroyed by US occupation forces as well as Iraqi citizens.[131]

Battle of Baghdad

Aniconism

Censorship by religion

Cult image

Cultural Revolution

Icon

Iconolatry

List of destroyed heritage

Lost artworks

Natural theology

Slighting

Council of Constantinople (843)

Alloa, Emmanuel (2013). "Visual Studies in Byzantium: A Pictorial Turnavant la lettre". Journal of Visual Culture. 12 (1). Sage: 3–29. :10.1177/1470412912468704. ISSN 1470-4129. S2CID 191395643. (On the conceptual background of Byzantine iconoclasm)

doi

(1988). England's Iconoclasts: Laws against images. Vol. 1. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822438-9.

Aston, Margaret

—— 2016. Broken Idols of the English Reformation. .

Cambridge University Press

Balafrej, Lamia (2 September 2015). "Islamic iconoclasm, visual communication and the persistence of the image". Interiors. 6 (3). Informa UK: 351–366. :10.1080/20419112.2015.1125659. ISSN 2041-9112. S2CID 131284640.

doi

Barasch, Moshe. 1992. Icon: Studies in the History of an Idea. . ISBN 978-0-8147-1172-9.

New York University Press

Beiner, Guy (2021). "When Monuments Fall: The Significance of Decommemorating". Éire-Ireland. 56 (1): 33–61. :10.1353/eir.2021.0001. S2CID 240526743.

doi

Besançon, Alain. 2000. The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. . ISBN 978-0-226-04414-9.

University of Chicago Press

Bevan, Robert. 2006. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. . ISBN 978-1-86189-319-2.

Reaktion Books

Boldrick, Stacy, , and Richard Clay, eds. 2014. Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present. Ashgate. (Scholarly studies of the destruction of images from prehistory to the Taliban.)

Leslie Brubaker

Calisi, Antonio. 2017. I Difensori Dell'icona: La Partecipazione Dei Vescovi Dell'Italia Meridionale Al Concilio Di Nicea II 787. . ISBN 978-1978401099.

CreateSpace

Freedberg, David. 1977. "." Pp. 165–77 in Iconoclasm: Papers Given at the Ninth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, edited by A. Bryer and J. Herrin. University of Birmingham, Centre for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 978-0-7044-0226-3.

The Structure of Byzantine and European Iconoclasm

ISBN

Gamboni, Dario (1997). The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Reaktion Books. 978-1-86189-316-1.

ISBN

Gwynn, David M (2007). (PDF). Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 47: 225–251. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-16. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

"From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy"

Hennaut, Eric (2000). . Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

La Grand-Place de Bruxelles

Ivanovic, Filip (2010). Symbol and Icon: Dionysius the Areopagite and the Iconoclastic Crisis. Pickwick. 978-1-60899-335-2.

ISBN

Karahan, Anne (2014). "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Ideology and Quest for Power". In Kolrud, Kristine; Prusac, M. (eds.). Iconoclasm from antiquity to modernity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. pp. 75–94. 978-1-4094-7033-5. OCLC 841051222.

ISBN

Lambourne, Nicola (2001). . Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1285-7.

War Damage in Western Europe: The Destruction of Historic Monuments During the Second World War

Narain, Harsh (1993). The Ayodhya Temple Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources. Delhi: Penman Publishers.

Sita Ram Goel, Harsh Narain, Jay Dubashi, and Ram Swarup. 1990. Hindu Temples – What Happened to Them Vol. I, (A Preliminary Survey). ISBN 81-85990-49-2

Shourie, Arun

Velikov, Yuliyan (2011). Obrazŭt na Nevidimii︠a︡ : ikonopochitanieto i ikonootrit︠s︡anieto prez osmi vek [Image of the Invisible. Image Veneration and Iconoclasm in the Eighth Century] (in Bosnian). Veliko Tarnovo: Veliko Tarnovo University. 978-954-524-779-8. OCLC 823743049.

ISBN

Weeraratna, Senaka ' Repression of Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Portuguese' (1505 -1658)

Teodoro Studita, Contro gli avversari delle icone, Emanuela Fogliadini (Prefazione), Antonio Calisi (Traduttore), Jaca Book, 2022, 978-8816417557

ISBN

(PDF) (in French). Vol. 1B: Pentagone E-M. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1993.

Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles

by Kerry Skemp, April 5, 2009

![16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[35][36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG/441px-2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG)

![The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[72] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[73][74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg/420px-Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/196px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![Rani Ki Vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Rani_ki_vav1.jpg/402px-Rani_ki_vav1.jpg)

![Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0e/Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg/562px-Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg)