Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centered in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans".[a] Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of state Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier "Roman Empire" and the later "Byzantine Empire".

"Byzantine" redirects here. For other uses, see Byzantine (disambiguation).

Byzantine Empire

Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul)

16,000,000

26,000,000

7,000,000

12,000,000

2,000,000

Solidus, denarius, and hyperpyron

During the earlier Pax Romana period, the western parts of the empire became increasingly Latinised, while the eastern parts largely retained their preexisting Hellenistic culture. This created a dichotomy between the Greek East and Latin West. These cultural spheres continued to diverge after Constantine I (r. 324–337) moved the capital to Constantinople and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the state religion, and other religious practices were proscribed. Greek gradually replaced Latin for official use as Latin fell into disuse.

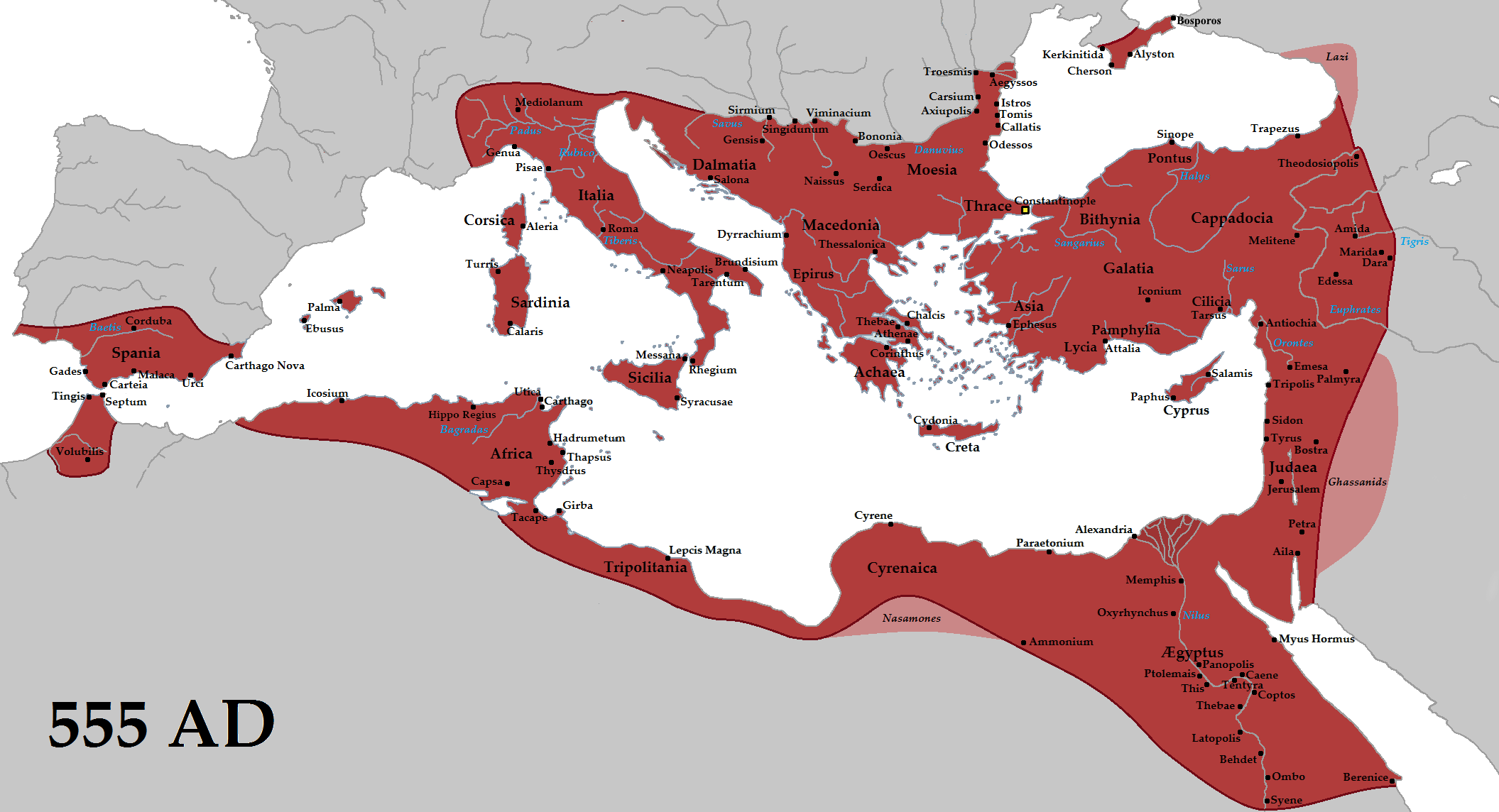

The empire experienced several cycles of decline and recovery throughout its history, reaching its greatest extent after the fall of the west during the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), who briefly reconquered much of Italy and the western Mediterranean coast. The appearance of plague and a devastating war with Persia exhausted the empire's resources; the early Muslim conquests that followed saw the loss of the empire's richest provinces—Egypt and Syria—to the Rashidun Caliphate. In 698, Africa was lost to the Umayyad Caliphate, but the empire subsequently stabilised under the Isaurian dynasty. The empire was able to expand once more under the Macedonian dynasty, experiencing a two-century-long renaissance. This came to an end in 1071, with the defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. Thereafter, periods of civil war and Seljuk incursion resulted in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The empire recovered during the Komnenian restoration, and Constantinople would remain the largest and wealthiest city in Europe until the 13th century.

The empire was dissolved in 1204, following the sack of Constantinople by Latin armies at the end of the Fourth Crusade; its former territories were then divided into competing Greek and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the reconstituted empire would wield only regional power during its final two centuries of existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans in perennial wars fought throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 ultimately brought the empire to an end. Many refugees who had fled the city after its capture settled in Italy and throughout Europe, helping to ignite the Renaissance. The fall of Constantinople is sometimes used to mark the dividing line between the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

Influences from Byzantine architecture, particularly in religious buildings, can be found in diverse regions from Egypt and Arabia to Russia and Romania. Byzantine architecture is known for the use of domes, and pendentive architecture was invented in the Byzantine Empire. In contrast to the basilica plans favored in medieval Western European churches, Byzantine churches usually had more centralized ground plans, such as the cross-in-square plan deployed in many Middle Byzantine churches.[209] It also often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds. Byzantine architects used marble mostly as interior cladding, in contrast to the structural roles it had for the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows. Mosaics were used to cover brick walls and any other surface where fresco would not resist. Good examples of mosaics from the proto-Byzantine era are in Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki (Greece), the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and the Basilica of San Vitale, both in Ravenna (Italy), and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Christian liturgies were held in the interior of the churches, the exterior usually having little to no ornamentation.[210][211]

![Christ as the Good Shepherd; c. 425–430; mosaic; width: c. 3 m; Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (Ravenna, Italy)[212]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/%22The_good_Shepherd%22_mosaic_-_Mausoleum_of_Galla_Placidia.jpg/150px-%22The_good_Shepherd%22_mosaic_-_Mausoleum_of_Galla_Placidia.jpg)

![Diptych Leaf with a Byzantine Empress; 6th century; ivory with traces of gilding and leaf; height: 26.5 cm (10.4 in); Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)[213]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/KHM_Wien_Kaiserin_Ariadne_X_39.jpg/78px-KHM_Wien_Kaiserin_Ariadne_X_39.jpg)

![Collier; late 6th–7th century; gold, an emerald, a sapphire, amethysts and pearls; diameter: 23 cm (9.1 in); from a Constantinopolitan workshop; Antikensammlung Berlin (Berlin, Germany)[214]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Officina_costantinopolitana%2C_tesoro_di_asyut_%28egitto%29%2C_V-VI_sec_ca._01_collier.JPG/150px-Officina_costantinopolitana%2C_tesoro_di_asyut_%28egitto%29%2C_V-VI_sec_ca._01_collier.JPG)