Illuminated manuscript

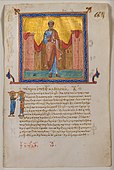

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers and liturgical books such as psalters and courtly literature, the practice continued into secular texts from the 13th century onward and typically include proclamations, enrolled bills, laws, charters, inventories, and deeds.[1][2]

For the art of miniature painting, see Miniature (illuminated manuscript).

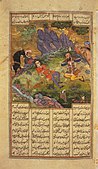

The earliest surviving illuminated manuscripts are a small number from late antiquity, and date from between 400 and 600. Examples include the Vergilius Romanus, Vergilius Vaticanus, and the Rossano Gospels.[3] The majority of extant manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many survive from the Renaissance. While Islamic manuscripts can also be called illuminated and use essentially the same techniques, comparable Far Eastern and Mesoamerican works are described as painted.

Most manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment until the 2nd century BCE, when a more refined material called vellum, made from stretched calf skin, was supposedly introduced by King Eumenes II of Pergamum. This gradually became the standard for luxury illuminated manuscripts,[4] although modern scholars are often reluctant to distinguish between parchment and vellum, and the skins of various animals might be used. The pages were then normally bound into codices (singular: codex), that is the usual modern book format, although sometimes the older scroll format was used, for various reasons. A very few illuminated fragments also survive on papyrus. Books ranged in size from ones smaller than a modern paperback, such as the pocket gospel, to very large ones such as choirbooks for choirs to sing from, and "Atlantic" bibles, requiring more than one person to lift them.[5]

Paper manuscripts appeared during the Late Middle Ages. The untypically early 11th century Missal of Silos is from Spain, near to Muslim paper manufacturing centres in Al-Andaluz. Textual manuscripts on paper become increasingly common, but the more expensive parchment was mostly used for illuminated manuscripts until the end of the period. Very early printed books left spaces for red text, known as rubrics, miniature illustrations and illuminated initials, all of which would have been added later by hand. Drawings in the margins (known as marginalia) would also allow scribes to add their own notes, diagrams, translations, and even comic flourishes.[6]

The introduction of printing rapidly led to the decline of illumination. Illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in the early 16th century but in much smaller numbers, mostly for the very wealthy. They are among the most common items to survive from the Middle Ages; many thousands survive. They are also the best surviving specimens of medieval painting, and the best preserved. Indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of painting.

Patrons[edit]

Monasteries produced manuscripts for their own use; heavily illuminated ones tended to be reserved for liturgical use in the early period, while the monastery library held plainer texts. In the early period manuscripts were often commissioned by rulers for their own personal use or as diplomatic gifts, and many old manuscripts continued to be given in this way, even into the Early Modern period. Especially after the book of hours became popular, wealthy individuals commissioned works as a sign of status within the community, sometimes including donor portraits or heraldry: "In a scene from the New Testament, Christ would be shown larger than an apostle, who would be bigger than a mere bystander in the picture, while the humble donor of the painting or the artist himself might appear as a tiny figure in the corner."[5] The calendar was also personalized, recording the feast days of local or family saints. By the end of the Middle Ages many manuscripts were produced for distribution through a network of agents, and blank spaces might be reserved for the appropriate heraldry to be added locally by the buyer.