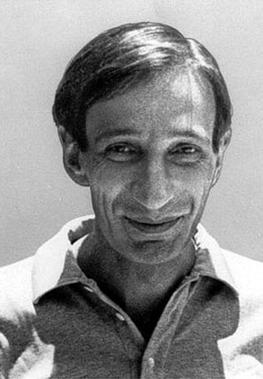

Ivan Illich

Ivan Dominic Illich (/ɪˌvɑːn ˈɪlɪtʃ/ iv-AHN IL-itch, German: [ˈiːvan ˈɪlɪtʃ]; 4 September 1926 – 2 December 2002) was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic.[1] His 1971 book Deschooling Society criticises modern society's institutional approach to education, an approach that constrains learning to narrow situations in a fairly short period of the human lifespan. His 1975 book Medical Nemesis, importing to the sociology of medicine the concept of medical harm, argues that industrialised society widely impairs quality of life by overmedicalising life, pathologizing normal conditions, creating false dependency, and limiting other more healthful solutions.[2] Illich called himself "an errant pilgrim."[3]

This article is about the Austrian philosopher. For the novella, see The Death of Ivan Ilyich. For the Russian philosopher, see Ivan Ilyin.

Ivan Illich

December 2, 2002 (aged 76)

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Ivan Dominic Illich was born on 4 September 1926 in Vienna, Austria, to Gian Pietro Ilic (Ivan Peter Illich) and Ellen Rose "Maexie" née Regenstreif-Ortlieb.[4] His father was a civil engineer and a diplomat from a landed Catholic family of Dalmatia, with property in the city of Split and wine and olive oil estates on the island of Brač. His mother came from a Jewish family that had converted to Christianity from Germany and Austria-Hungary (Czernowitz, Bukowina).[5] Ellen Illich was baptized Lutheran but converted to Catholicism upon marriage.[6][7] Her father, Friedrich "Fritz" Regenstreif, was an industrialist who made his money in the lumber trade in Bosnia, later settling in Vienna, where he built an art nouveau villa.

Ellen Illich traveled to Vienna to be attended by the best doctors during birth. Ivan's father was not living in Central Europe at the time. When Ivan was three months old, he was taken along with his nurse to Split, Dalmatia (by then part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), to be shown to his paternal grandfather. There he was baptized on 1 December 1926.[8] In 1929 twin boys, Alexander and Michael, were born in the family.

Work in Europe and the Americas[edit]

In 1942, Ellen Illich and her three children—Ivan, Alexander, and Michael—left Vienna, Austria for Florence, Italy, escaping the Nazi persecution of Jews. Illich finished high school in Florence, and then went on to study histology and crystallography at the local University of Florence.[9] Hoping to return to Austria following World War II, he enrolled in a doctorate in medieval history at the University of Salzburg[10] with the hope of gaining legal residency as he was undocumented.[9] He wrote a dissertation focusing on the historian Arnold J. Toynbee, a subject to which he would return in his later years. While working on his doctorate, he returned to Italy where he studied theology and philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, as he wanted to become a Catholic priest. He was ordained as a Catholic priest in Rome in 1951 and served his first Mass in the catacombs where the early Roman Christians hid from their persecutors.[5]

A polyglot, Illich spoke Italian, Spanish, French, and German fluently.[10][11][12] He later learned Croatian, the language of his grandfathers, then Ancient Greek and Latin, in addition to Portuguese, Hindi, English, and other languages.[10]

Following his ordination in 1951, he moved to the United States in order to pursue postgraduate studies at Princeton University. However, he deviated from these plans in order to become a parish priest at the Church of the Incarnation in Washington Heights, at that time a barrio of newly-arrived Puerto Rican immigrants. At Incarnation, Illich preached under the name of "John Illich", at the suggestion of the parish's pastor, who said that the name Ivan "sounded communist". At Incarnation, Illich rose to prominence as an ally of the large Puerto Rican community in Washington Heights, organizing cultural outlets for them, such as the San Juan Fiesta, a celebration of Puerto Rico and its patron saint which eventually involved into the still-extant Puerto Rican Day Parade. The success of Illich attracted the attention of the Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Spellman, and in 1956, at the age of 30, he was appointed vice rector of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico, "a position he managed to keep for several years before getting thrown out—Illich was just a little too loud in his criticism of the Vatican's pronouncements on birth control and comparatively demure silence about the nuclear bomb."[13][14] It was in Puerto Rico that Illich met Everett Reimer, and the two began to analyze their own functions as "educational" leaders. In 1959, he traveled throughout South America on foot and by bus.[10][13]

The end of Illich's tenure at the university came in 1960 as the result of a controversy involving bishops James Edward McManus and James Peter Davis, who had denounced Governor Luis Muñoz Marín and his Popular Democratic Party for their positions in favor of birth control and divorce. The bishops also started their own rival Catholic party.[15] Illich later summarized his opposition:

Philosophical views[edit]

Illich followed the tradition of apophatic theology.[25] His lifework's leading thesis is that Western modernity, perverting Christianity, corrupts Western Christianity. A perverse attempt to encode the New Testament's principles as rules of behavior, duty, or laws, and to institutionalize them, without limits, is a corruption that Illich detailed in his analyses of modern Western institutions, including education, charity, and medicine, among others. Illich often used the Latin phrase Corruptio optimi quae est pessima, in English The corruption of the best is the worst.[5][26]

Illich believed that the Biblical God taking human form, the Incarnation, marked world history's turning point, opening new possibilities for love and knowledge. As in the First Epistle of John,[27] it invites any believer to seek God's face in everyone encountered.[5] Describing this new possibility for love, Illich refers to the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Influence[edit]

His first book, Deschooling Society, published in 1971, was a groundbreaking critique of compulsory mass education. He argued the oppressive structure of the school system could not be reformed. It must be dismantled in order to free humanity from the crippling effects of the institutionalization of all of life. He went on to critique modern mass medicine. Illich was highly influential among intellectuals and academics. He became known worldwide for his progressive polemics about how activity expressive of truly human values could be preserved and expanded in human culture in the face of multiple thundering forces of de-humanization.

In his several influential books, he argued that the overuse of the benefits of many modern technologies and social arrangements undermine human values and human self-sufficiency, freedom, and dignity. His in-depth critiques of mass education and modern mass medicine were especially, pointed, relevant; and perhaps, more timely now than during his life.

Health, argues Illich, is the capacity to cope with the human reality of death, pain, and sickness. Technology can benefit many; yet, modern mass medicine has gone too far, launching into a godlike battle to eradicate death, pain, and sickness. In doing so, it turns people into risk-averse consuming objects, turning healing into mere science, turning medical healers into mere drug-surgical technicians.[28][29][30]

The Dark Mountain Project, a creative cultural movement founded by Dougald Hine and Paul Kingsnorth that abandons the myths of modern societies and looks for other new stories that help us make sense of modernity, drew their inspiration from the ideas of Ivan Illich.[31]