Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (/ˈæŋɡrə, ˈæ̃ɡrə/ ANG-grə, French: [ʒɑ̃ oɡyst dɔminik ɛ̃ɡʁ]; 29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Ingres was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style. Although he considered himself a painter of history in the tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David, it is his portraits, both painted and drawn, that are recognized as his greatest legacy. His expressive distortions of form and space made him an important precursor of modern art, influencing Picasso, Matisse and other modernists.

"Ingres" redirects here. For other uses, see Ingres (disambiguation).

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

14 January 1867 (aged 86)

- Portrait of Monsieur Bertin (1832)

- The Turkish Bath (1863)

Born into a modest family in Montauban, he travelled to Paris to study in the studio of David. In 1802 he made his Salon debut, and won the Prix de Rome for his painting The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles. By the time he departed in 1806 for his residency in Rome, his style—revealing his close study of Italian and Flemish Renaissance masters—was fully developed, and would change little for the rest of his life. While working in Rome and subsequently Florence from 1806 to 1824, he regularly sent paintings to the Paris Salon, where they were faulted by critics who found his style bizarre and archaic. He received few commissions during this period for the history paintings he aspired to paint, but was able to support himself and his wife as a portrait painter and draughtsman.

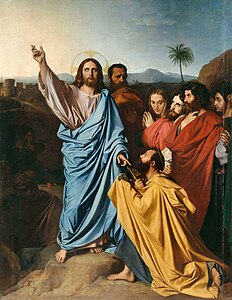

He was finally recognized at the Salon in 1824, when his Raphaelesque painting, The Vow of Louis XIII, was met with acclaim, and Ingres was acknowledged as the leader of the Neoclassical school in France. Although the income from commissions for history paintings allowed him to paint fewer portraits, his Portrait of Monsieur Bertin marked his next popular success in 1833. The following year, his indignation at the harsh criticism of his ambitious composition The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian caused him to return to Italy, where he assumed directorship of the French Academy in Rome in 1835. He returned to Paris for good in 1841. In his later years he painted new versions of many of his earlier compositions, a series of designs for stained glass windows, several important portraits of women, and The Turkish Bath, the last of his several Orientalist paintings of the female nude, which he finished at the age of 83.

Early years: Montauban and Toulouse[edit]

Ingres was born in Montauban, Tarn-et-Garonne, France, the first of seven children (five of whom survived infancy) of Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres (1755–1814) and his wife Anne Moulet (1758–1817). His father was a successful jack-of-all-trades in the arts, a painter of miniatures, sculptor, decorative stonemason, and amateur musician; his mother was the nearly illiterate daughter of a master wigmaker.[1] From his father the young Ingres received early encouragement and instruction in drawing and music, and his first known drawing, a study after an antique cast, was made in 1789.[2] Starting in 1786, he attended the local school École des Frères de l'Éducation Chrétienne, but his education was disrupted by the turmoil of the French Revolution, and the closing of the school in 1791 marked the end of his conventional education. The deficiency in his schooling would always remain for him a source of insecurity.[3]

In 1791, Joseph Ingres took his son to Toulouse, where the young Jean-Auguste-Dominique was enrolled in the Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture. There he studied under the sculptor Jean-Pierre Vigan, the landscape painter Jean Briant, and the neoclassical painter Guillaume-Joseph Roques. Roques' veneration of Raphael was a decisive influence on the young artist.[4] Ingres won prizes in several disciplines, such as composition, "figure and antique", and life studies.[5] His musical talent was developed under the tutelage of the violinist Lejeune, and from the ages of thirteen to sixteen he played second violin in the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse.[5]

From an early age he was determined to be a history painter, which, in the hierarchy of genres established by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture under Louis XIV, and continued well into the 19th Century, was considered the highest level of painting. He did not want to simply make portraits or illustrations of real life like his father; he wanted to represent the heroes of religion, history and mythology, to idealize them and show them in ways that explained their actions, rivaling the best works of literature and philosophy.[6]

Ingres and Delacroix[edit]

Ingres and Delacroix became, in the mid-19th century, the most prominent representatives of the two competing schools of art in France, neoclassicism and romanticism. Neo-classicism was based in large part on the philosophy of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), who wrote that art should embody "noble simplicity and calm grandeur". Many painters followed this course, including François Gérard, Antoine-Jean Gros, Anne-Louis Girodet, and Jacques-Louis David, the teacher of Ingres. A competing school, romanticism, emerged first in Germany, and moved quickly to France. It rejected the idea of the imitation of classical styles, which it described as "gothic" and "primitive". The Romanticists in French painting were led by Théodore Géricault and especially Delacroix. The rivalry first emerged at the Paris Salon of 1824, where Ingres exhibited The Vow of Louis XIII, inspired by Raphael, while Delacroix showed The Massacre at Chios, depicting a tragic event in the Greek War of Independence. Ingres's painting was calm, static and carefully constructed, while the work of Delacroix was turbulent, full of motion, colour, and emotion.[130]

The dispute between the two painters and schools reappeared at the 1827 Salon, where Ingres presented L'Apotheose d'Homer, an example of classical balance and harmony, while Delacroix showed The Death of Sardanapalus, another glittering and tumultuous scene of violence. The duel between the two painters, each considered the best of his school, continued over the years. Paris artists and intellectuals were passionately divided by the conflict, although modern art historians tend to regard Ingres and other Neoclassicists as embodying the Romantic spirit of their time.[131]

At the 1855 Universal Exposition, both Delacroix and Ingres were well represented. The supporters of Delacroix and the romantics heaped abuse on the work of Ingres. The Brothers Goncourt described "the miserly talent" of Ingres: "Faced with history, M. Ingres calls vainly to his assistance a certain wisdom, decency, convenience, correction and a reasonable dose of the spiritual elevation that a graduate of a college demands. He scatters persons around the center of the action ... tosses here and there an arm, a leg, a head perfectly drawn, and thinks that his job is done..."[132]

Baudelaire also, previously sympathetic toward Ingres, shifted toward Delacroix. "M. Ingres can be considered a man gifted with high qualities, an eloquent evoker of beauty, but deprived of the energetic temperament which creates the fatality of genius."[133]

Delacroix himself was merciless toward Ingres. Describing the exhibition of works by Ingres at the 1855 Exposition, he called it "ridiculous ... presented, as one knows, in a rather pompous fashion ... It is the complete expression of an incomplete intelligence; effort and pretension are everywhere; nowhere is there found a spark of the natural."[134]

According to Ingres' student Paul Chenavard, later in their careers, Ingres and Delacroix accidentally met on the steps of the French Institute; Ingres put his hand out, and the two shook amicably.[135]

Pupils[edit]

Ingres was a conscientious teacher and was greatly admired by his students.[136] The best known of them is Théodore Chassériau, who studied with him from 1830, as a precocious eleven-year-old, until Ingres closed his studio in 1834 to return to Rome. Ingres considered Chassériau his truest disciple—even predicting, according to an early biographer, that he would be "the Napoleon of painting".[137]

By the time Chassériau visited Ingres in Rome in 1840, however, the younger artist's growing allegiance to the romantic style of Delacroix was apparent, leading Ingres to disown his favourite student, of whom he subsequently spoke rarely and censoriously. No other artist who studied under Ingres succeeded in establishing a strong identity; among the most notable of them were Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, Henri Lehmann, and Eugène Emmanuel Amaury-Duval.[138]

Violon d'Ingres[edit]

Ingres's well-known passion for playing the violin gave rise to a common expression in the French language, "violon d'Ingres", meaning a second skill beyond the one by which a person is mainly known.

Ingres was an amateur violin player from his youth, and played for a time as second violinist for the orchestra of Toulouse. When he was Director of the French Academy in Rome, he played frequently with the music students and guest artists. Charles Gounod, who was a student under Ingres at the Academy, merely noted that "he was not a professional, even less a virtuoso". Along with the student musicians, he performed Beethoven string quartets with Niccolò Paganini. In an 1839 letter, Franz Liszt described his playing as "charming", and planned to play through all the Mozart and Beethoven violin sonatas with Ingres. Liszt also dedicated his transcriptions of the 5th and 6th symphonies of Beethoven to Ingres on their original publication in 1840.[147]

The American avant-garde artist Man Ray used this expression as the title of a famous photograph[148] portraying Alice Prin (aka Kiki de Montparnasse) in the pose of the Valpinçon Bather with two f-holes painted on to make her body resemble a violin.