Jesus Seminar

The Jesus Seminar was a group of about 50 biblical criticism scholars and 100 laymen founded in 1985 by Robert Funk that originated under the auspices of the Westar Institute.[1][2] The seminar was very active through the 1980s and 1990s, and into the early 21st century.

Formation

1985

2006

To decide their collective view of the historicity of the deeds and sayings of Jesus of Nazareth

Votes with colored beads

150

Members of the Seminar used votes with colored beads to decide their collective view of the historicity of the deeds and sayings of Jesus of Nazareth.[3] They produced new translations of the New Testament and apocrypha to use as textual sources. They published their results in three reports: The Five Gospels (1993),[4] The Acts of Jesus (1998),[5] and The Gospel of Jesus (1999).[6] They also ran a series of lectures and workshops in various U.S. cities.

The work of The Jesus Seminar continued after the death of its founder (2005) and was succeeded by two seminars: The Seminar on God and the Human Future and The Christianity Seminar. The latter published its first report in 2022, After Jesus Before Christianity: A Historical Exploration of the First Two Centuries of Jesus Movements.[7] The seminars are the scholarly program units of Westar Institute. Westar publishes a bi-monthly magazine for the general public, The Fourth R: An Advocate for Religious Literacy.

Search for the "Historical Jesus"[edit]

The Seminar's reconstruction of the historical Jesus portrayed him as an itinerant Hellenistic Jewish sage and faith-healer who preached a gospel of liberation from injustice in startling parables and aphorisms.[4][5][6] An iconoclast, Jesus broke with established Jewish theological dogmas and social conventions both in his teachings and in his behavior, often by turning common-sense ideas upside down, confounding the expectations of his audience: he preached of "Heaven's imperial rule" (traditionally translated as "Kingdom of God") as being already present but unseen; he depicted God as a loving father; he fraternized with outsiders and criticized insiders.[4][5][6] According to the Seminar, Jesus was a mortal man born of two human parents, who did not perform nature miracles nor die as a substitute for sinners nor rise bodily from the dead.[4][5][6] Sightings of a risen Jesus represented the visionary experiences of some of his disciples rather than physical encounters.[4][5][6] While these claims, not accepted by conservative Christian laity, have been repeatedly made in various forms since the 18th century,[8] the Jesus Seminar addressed them in a unique manner with its consensual research methodology.

The Seminar treated the canonical gospels as historical sources that represent Jesus' actual words and deeds as well as elaborations of the early Christian community and of the gospel authors. The Fellows placed the burden of proof on those who advocate any passage's historicity. Unconcerned with canonical boundaries, they asserted that the Gospel of Thomas may have more authentic material than the Gospel of John.[9]

The Seminar held a number of premises or "scholarly wisdom" about Jesus when critically approaching the gospels. Members acted on the premise that Jesus did not hold an apocalyptic worldview, an opinion that is controversial in mainstream scholarly studies of Jesus.[10] The Fellows argued that the authentic words of Jesus, rather than revealing an apocalyptic eschatology which instructs his disciples to prepare for the end of the world, indicate that he preached a sapiential eschatology, which encourages all of God's children to repair the world.[11][12]

The methods and conclusions of the Jesus Seminar have come under harsh criticism from numerous biblical scholars, historians and clergy for a variety of reasons. Such critics assert, for example, that the Fellows of the Seminar were not all trained scholars, that their voting technique did not allow for nuance, that they were preoccupied with the Q source and with the Gospel of Thomas but omitted material in other sources such as the Gospel of the Hebrews, and that they relied excessively on the criterion of embarrassment.[9][13][14][15]

The scholars' translation[edit]

The Seminar began by translating the gospels into modern American English, producing what they call the "Scholars Version", first published in The Complete Gospels.[23] This translation uses current colloquialisms and contemporary phrasing in an effort to provide a contemporary sense of the gospel authors' styles, if not their literal words. The goal was to let the reader hear the message as a first-century listener might have. The translators avoided other translations' archaic, literal translation of the text, or a superficial update of it. For example, they translate "woe to you" as "damn you".[24] The authors of The Complete Gospels argue that some other gospel translations have attempted to unify the language of the gospels, while they themselves have tried to preserve each author's distinct voice.[25]

Current activities and fellows of the Jesus Seminar[edit]

Members of the Jesus Seminar have responded to their critics in various books and dialogues, which typically defend both their methodology and their conclusions. Among these responses are The Jesus Seminar and Its Critics by Robert J. Miller,[78] a member of the Seminar; The Apocalyptic Jesus: A Debate,[79] a dialogue with Allison, Borg, Crossan, and Stephen Patterson; The Jesus Controversy: Perspectives in Conflict,[80] a dialogue between Crossan, Johnson, and Werner H. Kelber. The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions,[81] by Borg and noted New Testament historian and Pauline scholar N. T. Wright demonstrated how two scholars with divergent theological positions can work together to creatively share and discuss their thoughts.

The Jesus seminar was active in the 1980s and 1990s. Early in the 21st century, another group called the "Acts Seminar" was formed by some previous members to follow similar approaches to biblical research.[2]

In March 2006, the Jesus Seminar began work on a new description of the emergence of the Jesus traditions through the first two centuries of the common era (CE). In this new phase, fellows of the Jesus Seminar on Christian Origins employ the methods and techniques pioneered by the original Jesus Seminar.[82]

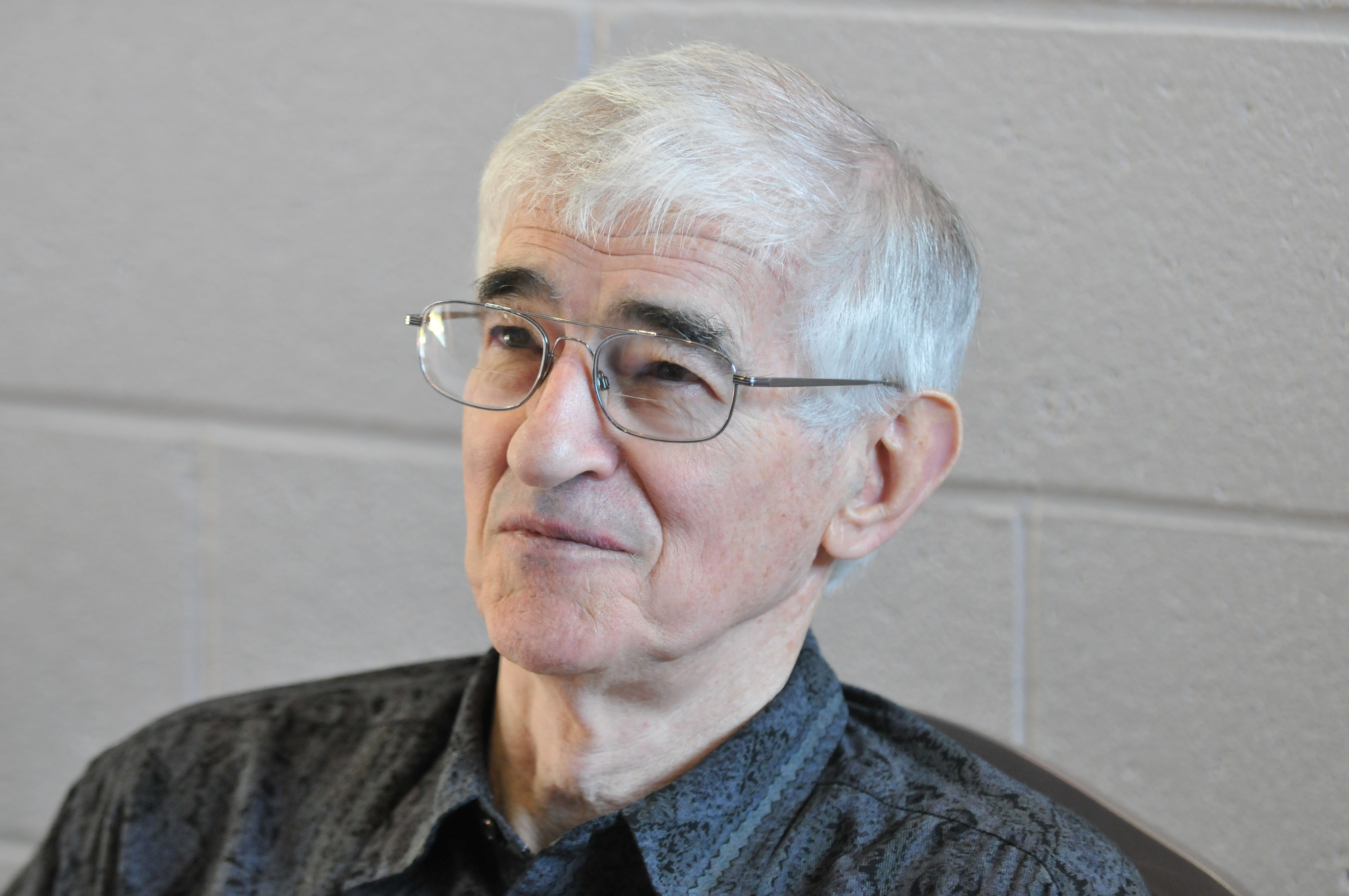

Robert Funk died in 2005, Marcus Borg in 2015, Stephen L. Harris in 2019, and Burton Mack in 2022, but notable surviving fellows of the Jesus Seminar include John Dominic Crossan and Robert M. Price. Borg was a liberal Christian who articulated the vision hypothesis to explain Jesus' resurrection.[83] Some view Crossan as an important voice in contemporary historical Jesus research, promoting the idea of a non-apocalyptic Jesus who preaches a sapiential eschatology.[20] Funk was a well-known scholar of recent American research into Jesus' parables.[84] Harris was the author of several books on religion, including university-level textbooks.[85] Mack described Jesus as a Galilean Cynic, based on the elements of the Q document that he considers to be earliest.[86]