Jim Crow laws

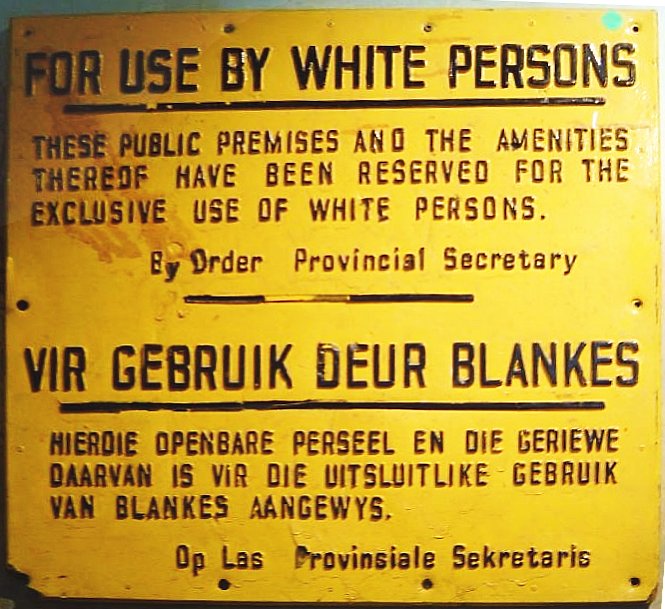

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, "Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American.[1] Such laws remained in force until 1965.[2] Formal and informal segregation policies were present in other areas of the United States as well, even as several states outside the South had banned discrimination in public accommodations and voting.[3][4] Southern laws were enacted by white-dominated state legislatures (Redeemers) to disenfranchise and remove political and economic gains made by African Americans during the Reconstruction era.[5] Such continuing racial segregation was also supported by the successful Lily-white movement.[6]

"Jim Crow" redirects here. For other uses, see Jim Crow (disambiguation).

In practice, Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America and in some others, beginning in the 1870s. Jim Crow laws were upheld in 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Supreme Court laid out its "separate but equal" legal doctrine concerning facilities for African Americans. Moreover, public education had essentially been segregated since its establishment in most of the South after the Civil War in 1861–1865. Companion laws excluded almost all African Americans from the vote in the South and deprived them of any representative government.

Although in theory, the "equal" segregation doctrine governed public facilities and transportation too, facilities for African Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to facilities for white Americans; sometimes, there were no facilities for the black community at all.[7][8] Far from equality, as a body of law, Jim Crow institutionalized economic, educational, political and social disadvantages and second class citizenship for most African Americans living in the United States.[7][8][9] After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in 1909, it became involved in a sustained public protest and campaigns against the Jim Crow laws, and the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine.

In 1954, segregation of public schools (state-sponsored) was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.[10][11][12] In some states, it took many years to implement this decision, while the Warren Court continued to rule against Jim Crow legislation in other cases such as Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964).[13] In general, the remaining Jim Crow laws were overturned by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Etymology

The earliest known use of the phrase "Jim Crow law" can be dated to 1884 in a newspaper article summarizing congressional debate.[14] The term appears in 1892 in the title of a New York Times article about Louisiana requiring segregated railroad cars.[15][16] The origin of the phrase "Jim Crow" has often been attributed to "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of black people performed by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface, first performed in 1828. As a result of Rice's fame, Jim Crow had become by 1838 a pejorative expression meaning "Negro". When southern legislatures passed laws of racial segregation directed against African Americans at the end of the 19th century, these statutes became known as Jim Crow laws.[15]

Remembrance

Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, houses the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, an extensive collection of everyday items that promoted racial segregation or presented racial stereotypes of African Americans, for the purpose of academic research and education about their cultural influence.[81]