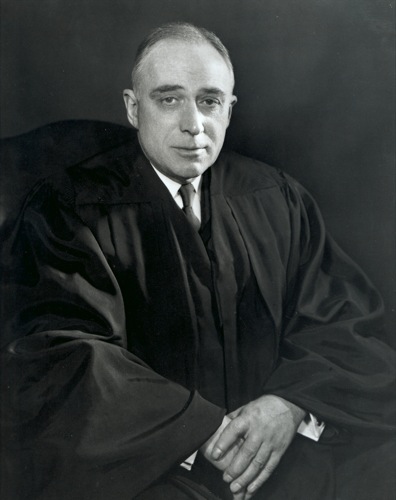

John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him from his grandfather, John Marshall Harlan, who served on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911.

John Marshall Harlan II

December 29, 1971 (aged 72)

Washington, D.C., U.S.

Emmanuel Church Cemetery, Weston, Connecticut, U.S.

1

- John Maynard Harlan (father)

John Marshall Harlan (grandfather)

Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and then at Princeton University. Awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Balliol College, Oxford.[1] Upon his return to the U.S. in 1923 Harlan worked in the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland while studying at New York Law School. Later he served as Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York and as Special Assistant Attorney General of New York. In 1954 Harlan was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and a year later president Dwight Eisenhower nominated Harlan to the United States Supreme Court following the death of Justice Robert H. Jackson.[2]

Harlan is often characterized as a member of the conservative wing of the Warren Court. He advocated a limited role for the judiciary, remarking that the Supreme Court should not be considered "a general haven for reform movements".[3] In general, Harlan adhered more closely to precedent, and was more reluctant to overturn legislation than many of his colleagues on the Court. He strongly disagreed with the doctrine of incorporation, which held that the provisions of the federal Bill of Rights applied to the state governments, not merely the Federal.[4] At the same time, he advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, arguing that it protected a wide range of rights not expressly mentioned in the United States Constitution.[4] Justice Harlan was gravely ill when he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.[5] He died from spinal cancer three months later, on December 29, 1971. After Harlan's retirement, President Nixon appointed William Rehnquist to replace him.

Early life and career[edit]

John Marshall Harlan was born on May 20, 1899, in Chicago.[2] He was the son of John Maynard Harlan, a Chicago lawyer and politician, and Elizabeth Flagg. He had three sisters.[6] Historically, Harlan's family had been politically active. His forebear George Harlan served as one of the governors of Delaware during the seventeenth century; his great-grandfather James Harlan was a congressman during the 1830s;[7] his grandfather, also John Marshall Harlan, was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911; and his uncle, James S. Harlan, was attorney general of Puerto Rico and then chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission.[5][7]

In his younger years, Harlan attended The Latin School of Chicago.[1] He later attended two boarding high schools in the Toronto Area, Canada: Upper Canada College and Appleby College.[1] Upon graduation from Appleby, Harlan returned to the U.S. and in 1916 enrolled at Princeton University. There, he was a member of the Ivy Club, served as an editor of The Daily Princetonian, and was class president during his junior and senior years.[1] After graduating from the university in 1920 with an Artium Baccalaureus degree, he received a Rhodes Scholarship to attend Balliol College, Oxford, making him the first Rhodes Scholar to sit on the Supreme Court.[7] He studied jurisprudence at Oxford for three years, returning from England in 1923.[5] Upon his return to the United States, he began work with the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland (which became Dewey & LeBoeuf), one of the leading law firms in the country, while studying law at New York Law School. He received his Bachelor of Laws in 1924 and earned admission to the bar in 1925.[8]

Between 1925 and 1927, Harlan served as Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, heading the district's Prohibition unit.[8] He prosecuted Harry M. Daugherty, former United States Attorney General.[5] In 1928, he was appointed Special Assistant Attorney General of New York, in which capacity he investigated a scandal involving sewer construction in Queens. He prosecuted Maurice E. Connolly, the Queens borough president, for his involvement in the affair.[2] In 1930, Harlan returned to his old law firm, becoming a partner one year later. At the firm, he served as chief assistant for senior partner Emory Buckner and followed him into public service when Buckner was appointed United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. As one of "Buckner's Boy Scouts", eager young Assistant United States Attorneys, Harlan worked on Prohibition cases, and swore off drinking except when the prosecutors visited the Harlan family fishing camp in Quebec, where Prohibition did not apply.[9] Harlan remained in public service until 1930, and then returned to his firm. Buckner had also returned to the firm,[9] and after Buckner's death, Harlan became the leading trial lawyer at the firm.[5]

As a trial lawyer Harlan was involved in a number of famous cases. One such case was the conflict over the estate left after the death in 1931 of Ella Wendel, who had no heirs and left almost all her wealth, estimated at $30–100 million, to churches and charities. However, a number of claimants, most of them imposters, filed suits in state and federal courts seeking part of her fortune. Harlan acted as the main defender of her estate and will as well as the chief negotiator. Eventually a settlement among lawful claimants was reached in 1933.[10] In the following years Harlan specialized in corporate law dealing with the cases like Randall v. Bailey,[11] concerning the interpretation of state law governing distribution of corporate dividends.[12] In 1940, he represented the New York Board of Higher Education unsuccessfully in the Bertrand Russell case in its efforts to retain Bertrand Russell on the faculty of the City College of New York; Russell was declared "morally unfit" to teach.[7] The future justice also represented boxer Gene Tunney in a breach of contract suit brought by a would-be fight manager, a matter settled out of court.[9][12]

In 1937, Harlan was one of five founders of a eugenics advocacy group called the Pioneer Fund, which had been formed to introduce Nazi ideas on eugenics to the United States. He had likely been invited into the group due to his expertise in non-profit organizations. Harlan served on the Pioneer Fund's board until 1954. He did not play a significant role in the fund.[13][14]

During World War II, Harlan volunteered for military duty, serving as a colonel in the United States Army Air Force from 1943 to 1945. He was the chief of the Operational Analysis Section of the Eighth Air Force in England.[5] He won the Legion of Merit from the United States, and the Croix de Guerre from both France and Belgium.[5] In 1946 Harlan returned to private law practice representing Du Pont family members against a federal antitrust lawsuit. In 1951, however, he returned to public service, serving as Chief Counsel to the New York State Crime Commission, where he investigated the relationship between organized crime and the state government as well as illegal gambling activities in New York and other areas.[5][7] During this period Harlan also served as a committee chairman of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, and to which he was later elected vice president. Harlan's main specialization at that time was corporate and antitrust law.[5]

Personal life[edit]

In 1928, Harlan married Ethel Andrews, who was the daughter of Yale history professor Charles McLean Andrews.[6] This was the second marriage for her. Ethel was originally married to New York architect Henry K. Murphy, who was twenty years her senior. After Ethel divorced Murphy in 1927, her brother John invited her to a Christmas party at Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland,[15] where she was introduced to John Harlan. They saw each other regularly afterwards and married on November 10, 1928, in Farmington, Connecticut.[6]

Harlan, a Presbyterian, maintained a New York City apartment, a summer home in Weston, Connecticut, and a fishing camp in Murray Bay, Quebec,[12] a lifestyle he described as "awfully tame and correct".[9] The justice played golf, favored tweeds, and wore a gold watch which had belonged to the first Justice Harlan.[9] In addition to carrying his grandfather's watch, when he joined the Supreme Court he used the same furniture which had furnished his grandfather's chambers.[9]

John and Ethel Harlan had one daughter, Evangeline Dillingham (born on February 2, 1932).[6] She was married to Frank Dillingham of West Redding, Connecticut, until his death, and had five children.[5][16] One of Eve's children, Amelia Newcomb, is the international news editor at The Christian Science Monitor[17] and has two children: Harlan, named after John Marshall Harlan II, and Matthew Trevithick.[18] Another daughter, Kate Dillingham, is a professional cellist and published author.

Second Circuit service[edit]

Harlan was nominated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 13, 1954, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit vacated by Judge Augustus Noble Hand. Harlan knew this court well, as he had often appeared before it and was friendly with many of the judges.[9] He was confirmed by the United States Senate on February 9, 1954, and received his commission on the next day. His service terminated on March 27, 1955, due to his elevation to the Supreme Court.[19]

Retirement and death[edit]

John M. Harlan's health began to deteriorate towards the end of his career. His eyesight began to fail during the late 1960s.[80] To cover this, he would bring materials to within an inch of his eyes, and have clerks and his wife read to him (once when the Court took an obscenity case, a chagrined Harlan had his wife read him Lady Chatterley's Lover).[20] Gravely ill, he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.[5]

Harlan died from spinal cancer[30] three months later, on December 29, 1971.[2] He was buried at the Emmanuel Church Cemetery in Weston, Connecticut.[81][82] President Richard Nixon considered nominating Mildred Lillie, a California appeals court judge, to fill the vacant seat; Lillie would have been the first female nominee to the Supreme Court. However, Nixon decided against Lillie's nomination after the American Bar Association found Lillie to be unqualified.[83] Thereafter, Nixon nominated William Rehnquist (a future Chief Justice), who was confirmed by the Senate.[80]

Despite his many dissents, Harlan has been described as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices of the twentieth century.[84] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.[85] Harlan's extensive professional and Supreme Court papers (343 cubic feet) were donated to Princeton University, where they are housed at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library and open to research.[86] Other papers repose at several other libraries. Ethel Harlan, his wife, outlived him by only a few months and died on June 12, 1972.[87] She suffered from Alzheimer's disease for the last seven years of her life.[15]