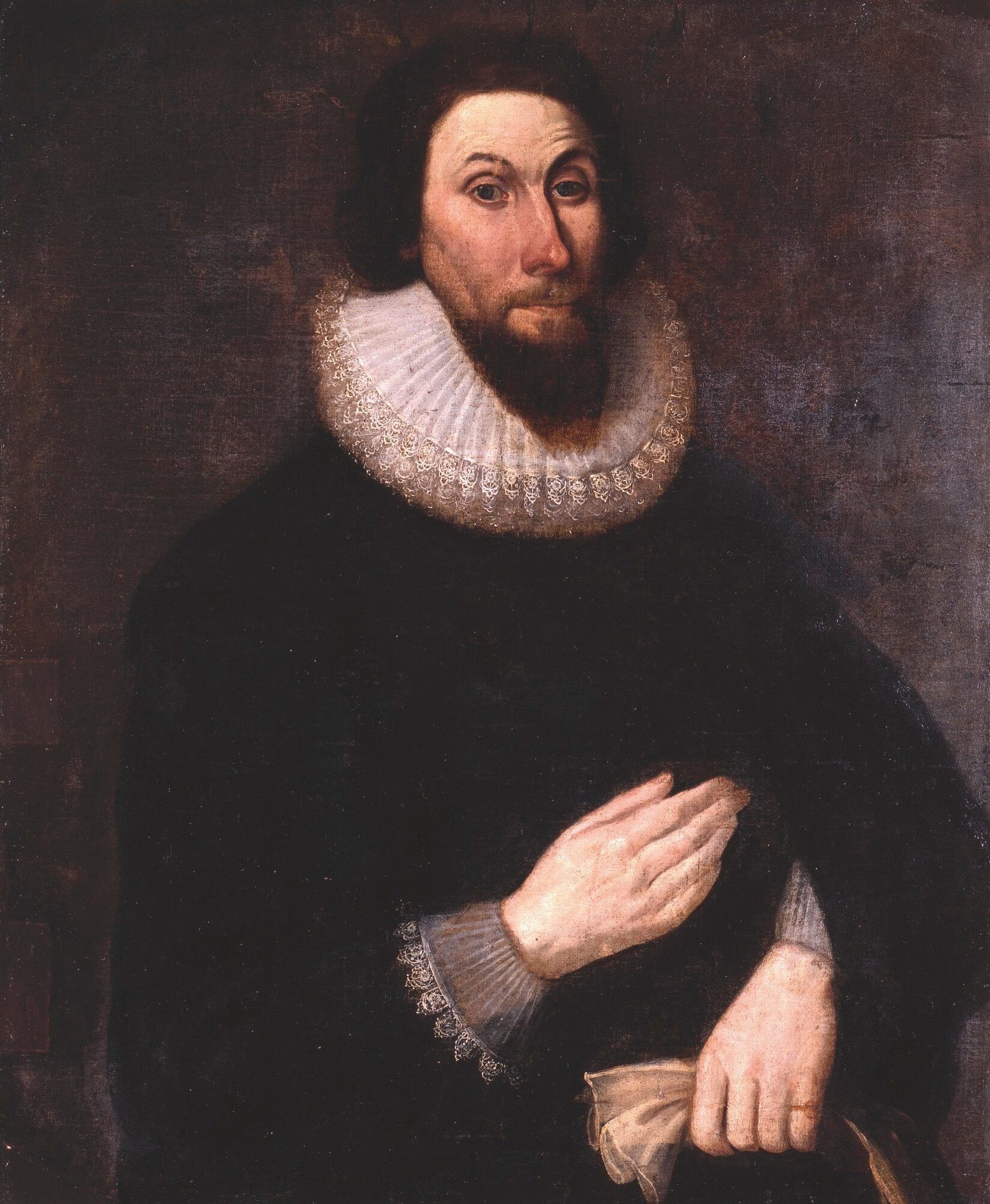

John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588[a] – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of colonists from England in 1630 and served as governor for 12 of the colony's first 20 years. His writings and vision of the colony as a Puritan "city upon a hill" dominated New England colonial development, influencing the governments and religions of neighboring colonies in addition to those of Massachusetts.

For other people named John Winthrop, see John Winthrop (disambiguation).

John Winthrop

Thomas Dudley

John Endecott

Thomas Dudley

John Endecott

Office established

- Simon Bradstreet

- William Hathorne

Herbert Pelham

12 January 1587/1588

Edwardstone, Suffolk, England

March 26, 1649 (aged 62)

Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony

-

Mary Forth(m. 1605; died 1615)

-

Thomasine Clopton(m. 1615; died 1616)

-

Martha Rainsborough(m. 1648)

16

Lawyer, governor

Winthrop was born into a wealthy land-owning and merchant family. He trained in the law and became Lord of the Manor at Groton in Suffolk, England. He was not involved in founding the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1628, but he became involved in 1629 when anti-Puritan King Charles I began a crackdown on Nonconformist religious thought. In October 1629, he was elected governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and he led a group of colonists to the New World in April 1630, founding a number of communities on the shores of Massachusetts Bay and the Charles River.

Between 1629 and his death in 1649, he served 18 annual terms as governor or lieutenant-governor and was a force of comparative moderation in the religiously conservative colony, clashing with the more conservative Thomas Dudley and the more liberal Roger Williams and Henry Vane. Winthrop was a respected political figure, and his attitude toward governance seems authoritarian to modern sensibilities. He resisted attempts to widen voting and other civil rights beyond a narrow class of religiously approved individuals, opposed attempts to codify a body of laws that the colonial magistrates would be bound by, and also opposed unconstrained democracy, calling it "the meanest and worst of all forms of government".[2] The authoritarian and religiously conservative nature of Massachusetts rule was influential in the formation of neighboring colonies, which were formed in some instances by individuals and groups opposed to the rule of the Massachusetts elders.

Winthrop's son John was one of the founders of the Connecticut Colony, and Winthrop himself wrote one of the leading historical accounts of the early colonial period. His long list of descendants includes famous Americans, and his writings continue to influence politicians today.

Massachusetts Bay Colony[edit]

Arrival[edit]

On April 8, 1630, four ships left the Isle of Wight carrying Winthrop and other leaders of the colony. Winthrop sailed on the Arbella, accompanied by his two young sons Samuel[b] and Stephen.[57] The ships were part of a larger fleet totalling 11 ships that carried about 700 migrants to the colony.[58] Winthrop's son Henry Winthrop missed the Arbella's sailing and ended up on the Talbot, which also sailed from Wight.[20][21] A sermon titled "A Modell of Christian Charitie", delivered either before or during the crossing, has historically been attributed to Winthrop, but the sermon's authorship is disputed; John Wilson or George Phillips, two ministers who sailed with the Arbella, may have authored the sermon.[59]

"A Modell of Christian Charitie" described the ideas and plans to keep the Puritan society strong in faith, while also comparing the struggles that they would have to overcome in the New World with the story of Exodus. The sermon used the now-famous phrase "City upon a Hill" to describe the ideals to which the colonists should strive, and that consequently "the eyes of all people are upon us."[60] The sermon also said, "In all times some must be rich some poore, some highe and eminent in power and dignitie; others meane and in subjection"; that is, all societies include some who are rich and successful and others who are poor and subservient—and both groups were equally important to the colony because both groups were members to the same community.[9]