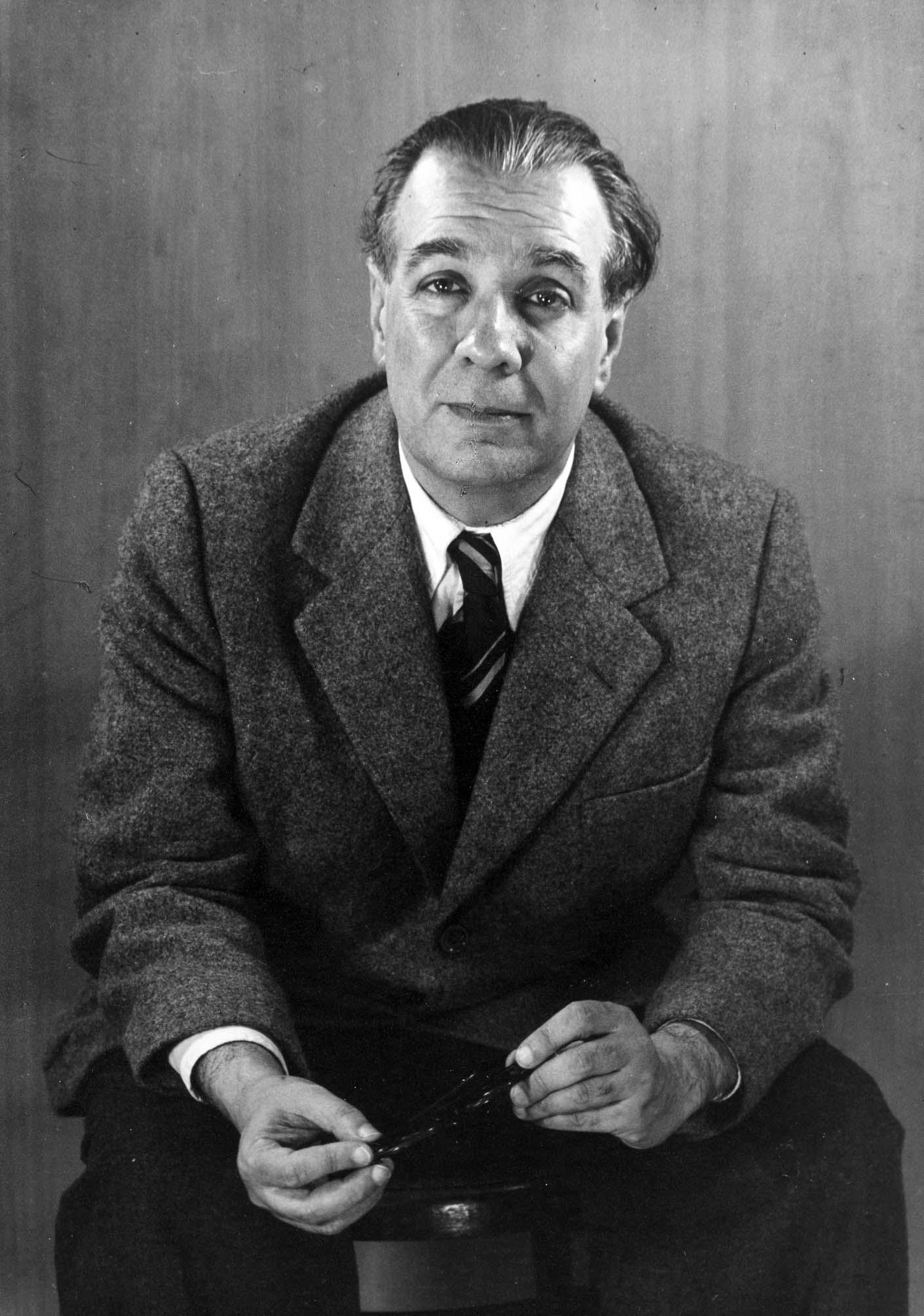

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (/ˈbɔːrhɛs/ BOR-hess,[2] Spanish: [ˈxoɾxe ˈlwis ˈboɾxes] ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known works, Ficciones (transl. Fictions) and El Aleph (transl. The Aleph), published in the 1940s, are collections of short stories exploring motifs such as dreams, labyrinths, chance, infinity, archives, mirrors, fictional writers and mythology.[3] Borges's works have contributed to philosophical literature and the fantasy genre, and have had a major influence on the magic realist movement in 20th century Latin American literature.[4]

"Borges" redirects here. For other people with the surname, see Borges (surname). For other uses, see Borges (disambiguation).

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo

24 August 1899

Buenos Aires, Argentina

14 June 1986 (aged 86)

Geneva, Switzerland

- Writer

- poet

- philosopher

- translator

- editor

- critic

- librarian

Spanish

- A Universal History of Infamy (1935)

- Ficciones (1944)

- El Aleph (1949)

- Labyrinths (1962)

- The Book of Sand (1975)

- Leonor Acevedo (mother)

- Jorge Guillermo Borges (father)

- Norah Borges (sister)

- Guillermo de Torre (brother-in-law)

- Francisco Borges (grandfather)

- Manuel Isidoro Suárez (great-grandfather)

Born in Buenos Aires, Borges later moved with his family to Switzerland in 1914, where he studied at the Collège de Genève. The family travelled widely in Europe, including Spain. On his return to Argentina in 1921, Borges began publishing his poems and essays in surrealist literary journals. He also worked as a librarian and public lecturer.[5] In 1955, he was appointed director of the National Public Library and professor of English Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. He became completely blind by the age of 55. Scholars have suggested that his progressive blindness helped him to create innovative literary symbols through imagination.[Note 1] By the 1960s, his work was translated and published widely in the United States and Europe. Borges himself was fluent in several languages.

In 1961, he came to international attention when he received the first Formentor Prize, which he shared with Samuel Beckett. In 1971, he won the Jerusalem Prize. His international reputation was consolidated in the 1960s, aided by the growing number of English translations, the Latin American Boom, and by the success of García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude.[6] He dedicated his final work, The Conspirators, to the city of Geneva, Switzerland.[7] Writer and essayist J. M. Coetzee said of him: "He, more than anyone, renovated the language of fiction and thus opened the way to a remarkable generation of Spanish-American novelists."[8]

Life and career[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo was born into an educated middle-class family on 24 August 1899.[9] They were in comfortable circumstances but not wealthy enough to live in downtown Buenos Aires, so the family resided in Palermo, then a poorer neighborhood. Borges's mother, Leonor Acevedo Suárez, came from a traditional Uruguayan family of criollo (Spanish) origin. Her family had been much involved in the European settling of South America and the Argentine War of Independence, and she spoke often of their heroic actions.[10]

His 1929 book Cuaderno San Martín includes the poem "Isidoro Acevedo", commemorating his grandfather, Isidoro de Acevedo Laprida, a soldier of the Buenos Aires Army. A descendant of the Argentine lawyer and politician Francisco Narciso de Laprida, Acevedo Laprida fought in the battles of Cepeda in 1859, Pavón in 1861, and Los Corrales in 1880. Acevedo Laprida died of pulmonary congestion in the house where his grandson Jorge Luis Borges was born.

According to a study by Antonio Andrade, Jorge Luis Borges had Portuguese ancestry: Borges's great-grandfather, Francisco, was born in Portugal in 1770, and lived in Torre de Moncorvo, in the North of the country before he emigrated to Argentina, where he married Cármen Lafinur.

Borges's own father, Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, was a lawyer, and wrote the novel El caudillo in 1921. Borges Haslam was born in Entre Ríos of Spanish, Portuguese, and English descent, the son of Francisco Borges Lafinur, a colonel, and Frances Ann Haslam, an Englishwoman. Borges Haslam grew up speaking English at home. The family frequently traveled to Europe. Borges Haslam wed Leonor Acevedo Suárez in 1898 and their offspring also included the painter Norah Borges, sister of Jorge Luis Borges.[10]

Aged ten, Jorge Luis Borges translated Oscar Wilde's The Happy Prince into Spanish. It was published in a local journal, but Borges's friends thought the real author was his father.[11] Borges Haslam was a lawyer and psychology teacher who harboured literary aspirations. Borges said his father "tried to become a writer and failed in the attempt", despite the 1921 opus El caudillo. Jorge Luis Borges wrote, "as most of my people had been soldiers and I knew I would never be, I felt ashamed, quite early, to be a bookish kind of person and not a man of action."[10]

Jorge Luis Borges was taught at home until the age of 11, was bilingual in Spanish and English, reading Shakespeare in the latter at the age of twelve.[10] The family lived in a large house with an English library of over one thousand volumes; Borges would later remark that "if I were asked to name the chief event in my life, I should say my father's library."[12]

His father gave up practicing law due to the failing eyesight that would eventually affect his son. In 1914, the family moved to Geneva, Switzerland, and spent the next decade in Europe.[10] In Geneva, Borges Haslam was treated by an eye specialist, while his son and daughter attended school. Jorge Luis learned French, read Thomas Carlyle in English, and began to read philosophy in German. In 1917, when he was eighteen, he met writer Maurice Abramowicz and began a literary friendship that would last for the remainder of his life.[10] He received his baccalauréat from the Collège de Genève in 1918.[13][Note 2] The Borges family decided that, due to political unrest in Argentina, they would remain in Switzerland during the war. After World War I, the family spent three years living in various cities: Lugano, Barcelona, Majorca, Seville, and Madrid.[10] They remained in Europe until 1921.

At that time, Borges discovered the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer and Gustav Meyrink's The Golem (1915) which became influential to his work. In Spain, Borges fell in with and became a member of the avant-garde, anti-Modernismo Ultraist literary movement, inspired by Guillaume Apollinaire and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, close to the Imagists. His first poem, "Hymn to the Sea", written in the style of Walt Whitman, was published in the magazine Grecia.[14] While in Spain, he met such noted Spanish writers as Rafael Cansinos Assens and Ramón Gómez de la Serna.[15]

Legacy and influence[edit]

Maria Kodama, his widow and heir on the basis of the marriage and two wills, gained control over his works. Her assertive administration of his estate resulted in a bitter dispute with the French publisher Gallimard regarding the republication of the complete works of Borges in French, with Pierre Assouline in Le Nouvel Observateur (August 2006) calling her "an obstacle to the dissemination of the works of Borges". Kodama took legal action against Assouline, considering the remark unjustified and defamatory, asking for a symbolic compensation of one euro.[59][60][61]

Kodama also rescinded all publishing rights for existing collections of his work in English, including the translations by Norman Thomas di Giovanni, in which Borges himself collaborated, and from which di Giovanni would have received an unusually high fifty percent of the royalties. Kodama commissioned new translations by Andrew Hurley, which have become the official translations in English.[62]

David Foster Wallace wrote: "The truth, briefly stated, is that Borges is arguably the great bridge between modernism and post-modernism in world literature. He is modernist in that his fiction shows a first-rate human mind stripped of all foundations of religious or ideological certainty – a mind turned wholly inward on itself. His stories are inbent and hermetic, with the oblique terror of a game whose rules are unknown and its stakes everything."[63]