Kievan Rus'

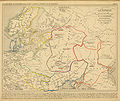

Kievan Rus',[a][b] also known as Kyivan Rus',[c][7][8] was a state and later an amalgam of principalities[9] in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.[10] The name was coined by Russian historians in the 19th century. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse,[11][12] and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik.[13] The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor,[d] with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus' derived from what is now the capital of Ukraine.[12][7] At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rus' stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east,[15][16] uniting the East Slavic tribes.[10]

For other historical states known as Rus', see Rus.

Kievan Rus'

Kiev (882–1240)

- Slavic paganism (native faith of Slavs)

- Reformed state paganism (official until 10th century)

- Orthodox Christianity (official since 10th cent.)

- Norse paganism (locally practiced)

- Finnish paganism (native faith of Finnic peoples)

c. 880

965–969

c. 988

1050s[2]

1237–1241

1240

1,330,000 km2 (510,000 sq mi)

5.4 million

According to the Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to unite East Slavic lands into what would become Kievan Rus' was Oleg the Wise (r. 879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east,[10] and took control of the city. Sviatoslav I (r. 943–972) achieved the first major territorial expansion of the state, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazars. Vladimir the Great (r. 980–1015) spread Christianity with his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev and beyond. Kievan Rus' reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, shortly after his death.[2]

The state began to decline in the late 11th century, gradually disintegrating into various rival regional powers throughout the 12th century.[17] It was further weakened by external factors, such as the decline of the Byzantine Empire, its major economic partner, and the accompanying diminution of trade routes through its territory.[18] It finally fell to the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century, though the Rurik dynasty would continue to rule until the death of Feodor I of Russia in 1598.[19]

History

Origin

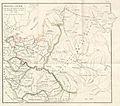

Prior to the emergence of Kievan Rus' in the 9th century, most of the area north of the Black Sea was primarily populated by eastern Slavic tribes.[36] In the northern region around Novgorod were the Ilmen Slavs[37] and neighboring Krivichi, who occupied territories surrounding the headwaters of the West Dvina, Dnieper and Volga rivers. To their north, in the Ladoga and Karelia regions, were the Finnic Chud tribe. In the south, in the area around Kiev, were the Poliane,[38] the Drevliane to the west of the Dnieper, and the Severiane to the east. To their north and east were the Vyatichi, and to their south was forested land settled by Slav farmers, giving way to steppelands populated by nomadic herdsmen.[39]

There was once controversy over whether the Rus' were Varangians or Slavs (see anti-Normanism), however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture.[e] This uncertainty is due largely to a paucity of contemporary sources. Attempts to address this question instead rely on archaeological evidence, the accounts of foreign observers, and legends and literature from centuries later.[41] To some extent the controversy is related to the foundation myths of modern states in the region.[4] This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies in a number of states. This was seen in the Stalinist period, when Soviet historiography sought to distance the Rus' from any connection to Germanic tribes, in an effort to dispel Nazi propaganda claiming the Russian state owed its existence and origins to the supposedly racially superior Norse tribes.[42] More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project.[43] Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rus' have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.[44]

While Varangians were Norse traders and Vikings,[45] some Russian and Ukrainian nationalist historians argue that the Rus' were themselves Slavs.[46][47][48] Normanist theories focus on the earliest written source for the East Slavs, the Primary Chronicle, which was produced in the 12th century.[49] Nationalist accounts on the other hand have suggested that the Rus' were present before the arrival of the Varangians,[50] noting that only a handful of Scandinavian words can be found in Russian and that Scandinavian names in the early chronicles were soon replaced by Slavic names.[51]

Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rus' and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language.[52][53] Though the debate over the origin of the Rus' remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rus' were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, "in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs".[40]

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an Arab traveler during the 10th century, provided one of the earliest written descriptions of the Rus': "They are as tall as a date palm, blond and ruddy, so that they do not need to wear a tunic nor a cloak; rather the men among them wear garments that only cover half of his body and leaves one of his hands free."[54] Liutprand of Cremona, who was twice an envoy to the Byzantine court (949 and 968), identifies the "Russi" with the Norse ("the Russi, whom we call Norsemen by another name")[55] but explains the name as a Greek term referring to their physical traits ("A certain people made up of a part of the Norse, whom the Greeks call [...] the Russi on account of their physical features, we designate as Norsemen because of the location of their origin.").[56] Leo the Deacon, a 10th-century Byzantine historian and chronicler, refers to the Rus' as "Scythians" and notes that they tended to adopt Greek rituals and customs.[57]