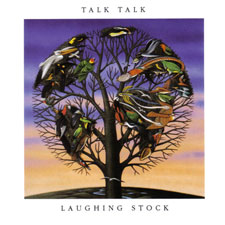

Laughing Stock

Laughing Stock is the fifth and final studio album by English band Talk Talk, released in 1991. Following their previous release Spirit of Eden (1988), bassist Paul Webb left the group, which reduced Talk Talk to the duo of singer/multi-instrumentalist Mark Hollis and drummer Lee Harris. Talk Talk then acrimoniously left EMI and signed to Polydor, who released the album on their newly revitalised jazz-based Verve Records label. Laughing Stock was recorded at London's Wessex Sound Studios from September 1990 to April 1991 with producer Tim Friese-Greene and engineer Phill Brown.

For other uses, see Laughing stock (disambiguation).

Like Spirit of Eden the album featured improvised instrumentation from a large ensemble of musicians. The demanding sessions were marked by Hollis' perfectionist tendencies and desire to create a suitable recording atmosphere. Engineer Phill Brown stated that the album, like its predecessor, was "recorded by chance, accident, and hours of trying every possible overdub idea."[7] The band split up following its release, effectively making Laughing Stock their last official release.

The album garnered significant critical praise, often cited as a watershed entry for the budding post-rock genre at the time of its release. Pitchfork retrospectively gave the album a 10 out of 10 score and named it the eleventh best album of the 1990s, saying it "makes its own environment and becomes more than the sum of its sounds."[8] In a 2007 list, Stylus Magazine named it the greatest post-rock album.[9]

Background[edit]

In 1986, Talk Talk, then a three-piece band consisting of leader and singer Mark Hollis alongside drummer Lee Harris and bassist Paul Webb, released their third album The Colour of Spring, which saw the band shift from their earlier, synthpop-oriented sound and featured a more organic art pop sound, where musicians improvised with their instruments for many hours, then Hollis and producer Tim Friese-Greene edited and arranged the performances to get the sound they wanted. A total of sixteen musicians appeared on the album. It became their most successful album, selling over two million copies and prompting a major world tour.[10][11] Nonetheless, for their next album Spirit of Eden (1988), the band chose to work towards an even more unconventional and uncommercial direction. The album was compiled from a lengthy recording process at in Studio 1 at London's Wessex Studios between 1987 and 1988 where the band worked again with Friese-Greene and engineer Phill Brown. Often working in darkness, the band recorded many hours of improvised performances which were heavily edited and re-arranged into the final album.[12]

Spirit of Eden was not a commercial success and although it would be acclaimed in later retrospective reviews, it initially polarized music critics.[11] Their record label EMI had doubts about whether it could have been successful many months in advance. They asked Hollis to re-record a song or replace material, but he refused to do so. By the time the masters were delivered later in the month, however, the label conceded that the album had been satisfactorily completed,[13] and chose to extend the band's recording contract. The band, however, wanted out of the contract. "I knew by that time that EMI was not the company this band should be with," manager Keith Aspden told Mojo. "I was fearful that the money wouldn't be there to record another album."[10] EMI and Talk Talk went to court to decide the issue.[14] Centered around whether EMI had notified the band in time about the contract extension, because as part of the agreement, the label had to send a written notice within three months after the completion of the album, but the band said they had notified them too late, arguing that the three-month period began once recording had finished; EMI argued that the three-month period did not begin until they were satisfied with the recording. Justice Andrew Morritt ruled in favour of EMI, but his decision was overturned in the Court of Appeal of England and Wales.[13] Talk Talk were released from the contract.

Nonetheless, in 1990, bassist Paul Webb left the band, officially reducing Talk Talk to the duo of Hollis and Harris.[15] EMI also issued two compilations without the band's consent in 1990 and 1991; Natural History: The Very Best of Talk Talk – a best-of/greatest hits album, and History Revisited – a collection of new remixes of old material from the band. Hollis was vocal in his opposition to both releases. Before the latter was released, Hollis sent letters requesting that the compilation be stopped, but EMI did not respond.[16] In November 1991, Talk Talk sued EMI, delivering four writs against their former record label.[17] The band claimed that material had been falsely attributed to them and that they were owed money from unpaid royalties.[17][18] Talk Talk won the case in 1992, and EMI agreed to withdraw and destroy all remaining copies of the album.[19][20] Manager Keith Aspden hoped that the case would set a precedent for future recording contracts.[18]

As the band's legal battle with EMI concerning their contract had freed them from the label,[13] the band began searching for other record labels, and eventually, their manager Keith Aspden signed them to Verve Records, the jazz offshoot label of Polydor Records. Hollis was pleased that they signed Talk Talk because the Mothers of Invention were once on Verve.[16] The band set to recording their new album soon after the contract was signed. Again hiring an array of guest musicians, producer/multi-instrumentalist Tim Friese-Greene and engineer Phill Brown, work began on Laughing Stock in 1990.

Release[edit]

When the band delivered Laughing Stock to Verve, Polydor were purported "gutted", wondering how they would be able to sell such an uncommercial record.[16] Sutherland recalled that "the first time I heard the record was at a dinner given for retailers by the record company at The New Serpentine Gallery. It was an embarrassingly desperate attempt over cocktails to convince store owners that they should stock a record which, the company was trying to infer, stood for quality over likely quantity of sales. Nobody knew where to look as Hollis' muted blues confessional purposely disintegrated into shivering feedback. A similar farce was, apparently, held in a Paris planetarium. Hollis attended both playbacks and survived. He says the Paris one wasn't too bad because, when the lights went out, it was close to the perfect way to listen to his music – with your eyes closed, watching your own mind movies. He didn't stick around in London, though – he had no desire to see people's reactions. He says he's proud of the record and, seeing as it wasn't made for other people, their opinions don't bother him."[16]

Hollis denied that there was any problem with Polydor, saying "the whole structure of the deal we have with this record company is understanding how we work. I suppose because it's on Verve some people will think we've been stuck under 'Jazz' but what on earth does jazz mean? It's such a vague term, isn't it? Without any question there are certain areas of jazz that are extremely important to me. Ornette Coleman is an example. But jazz as a term is as widely used and abused as soul – it no longer means what it should mean. Jazz has almost been bastardised to such an extent that, if you've got a saxophone on a record, it's jazz, which is a terrifying idea. It's like, where would you ever place Can? To me Tago Mago is an extremely important album that has elements of jazz in it, but I would never call it jazz. Basically, the deal is that I promise to give them the best album I can. I think they have options across four albums which, at the pace we work, is the next 12 years. What more can you say?"[16]

Verve Records released the album on 16 September 1991.[1] No official singles or music videos were released to promote the album.[1] Nonetheless, a limited edition box set entitled After the Flood / New Grass / Ascension Day was released in France, containing the aforementioned three songs from the album, with the former edited down as an "outtake", and two unreleased B-sides ("Stump", "5:09").[27] In the United States, a recording of an interview with Mark Hollis entitled Mark Hollis Talks About Laughing Stock was distributed on cassette.[28] Despite the lack of traditional promotion, the album reached number 26 on the UK Albums Chart, and stayed on the chart for two weeks.[29]

Unlike Talk Talk's other albums, the album has never been remastered for CD, but on 11 October 2011, Ba Da Bing Records released a remastered version of Laughing Stock on vinyl, marking the first time that the album has been issued on vinyl in the United States.[30] Pitchfork commented that the remastering on this re-release sounds "amazing, as good as the album's ever sounded, in any format. Which is crucial, because on some level Talk Talk's later albums are all about sound. How startling, isolated moments of sound, or a formless wash of sound, can wring emotions out of listeners as powerfully as any conventional melody."[23]

Note:

Talk Talk

Other musicians

Technical personnel