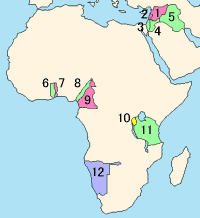

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing the internationally agreed terms for administering the territory on behalf of the League of Nations. Combining elements of both a treaty and a constitution, these mandates contained minority rights clauses that provided for the rights of petition and adjudication by the Permanent Court of International Justice.[1]

The mandate system was established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, entered into force on 28 June 1919. With the dissolution of the League of Nations after World War II, it was stipulated at the Yalta Conference that the remaining mandates should be placed under the trusteeship of the United Nations, subject to future discussions and formal agreements. Most of the remaining mandates of the League of Nations (with the exception of South West Africa) thus eventually became United Nations trust territories.

Two governing principles formed the core of the Mandate System, being non-annexation of the territory and its administration as a "sacred trust of civilisation" to develop the territory for the benefit of its native people.[2]

According to historian Susan Pedersen, colonial administration in the mandates did not differ substantially from colonial administration elsewhere. Even though the Covenant of the League committed the great powers to govern the mandates differently, the main difference appeared to be that the colonial powers spoke differently about the mandates than their other colonial possessions.[3]

Basis[edit]

The mandate system was established by Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, drafted by the victors of World War I. The article referred to territories which after the war were no longer ruled by their previous sovereign, but their peoples were not considered "able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world". The article called for such people's tutelage to be "entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake this responsibility".[4]

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and South African General Jan Smuts played influential roles in pushing for the establishment of a mandates system.[5] The mandates system reflected a compromise between Smuts (who wanted colonial powers to annex the territories) and Wilson (who wanted trusteeship over the territories).[6][7]

Later history[edit]

After the United Nations was founded in 1945 and the League of Nations was disbanded, all but one of the mandated territories became United Nations trust territories, a roughly equivalent status.[11] In each case, the colonial power that held the mandate on each territory became the administering power of the trusteeship, except that of the Empire of Japan, which had been defeated in World War II, lost its mandate over the South Pacific islands, which became a "strategic trust territory" known as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands under U.S. administration.

The sole exception to the transformation of the League of Nations mandates into UN trusteeships was that of South Africa and its mandated territory South West Africa. Rather than placing South West Africa under trusteeship like other former mandates, South Africa proposed annexation, a proposition rejected by the UN General Assembly. Despite South Africa's resistance, the International Court of Justice affirmed that South Africa continued to have international obligations regarding the South West Africa mandate. Eventually, in 1990, the mandated territory, now Namibia, gained independence, culminating from the Tripartite Accords and the resolution of the South African Border War — a prolonged guerrilla conflict against the apartheid regime that lasted from 1966 until 1990.

Nearly all the former League of Nations mandates had become sovereign states by 1990, including all of the former UN trust territories with the exception of a few successor entities of the gradually dismembered Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (formerly Japan's South Pacific Trust Mandate). These exceptions include the Northern Mariana Islands which is a commonwealth in political union with the U.S. with the status of unincorporated organised territory. The Northern Mariana Islands does elect its own governor to serve as territorial head of government, but it remains a U.S. territory with its head of state being the President of the United States and federal funds to the commonwealth administered by the Office of Insular Affairs of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Remnant Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, the heirs of the last territories of the Trust, attained final independence on 22 December 1990. (The UN Security Council ratified termination of trusteeship, effectively dissolving trusteeship status, on 10 July 1987.) The Republic of Palau, split off from the Federated States of Micronesia, became the last to effectively gain its independence, on 1 October 1994.