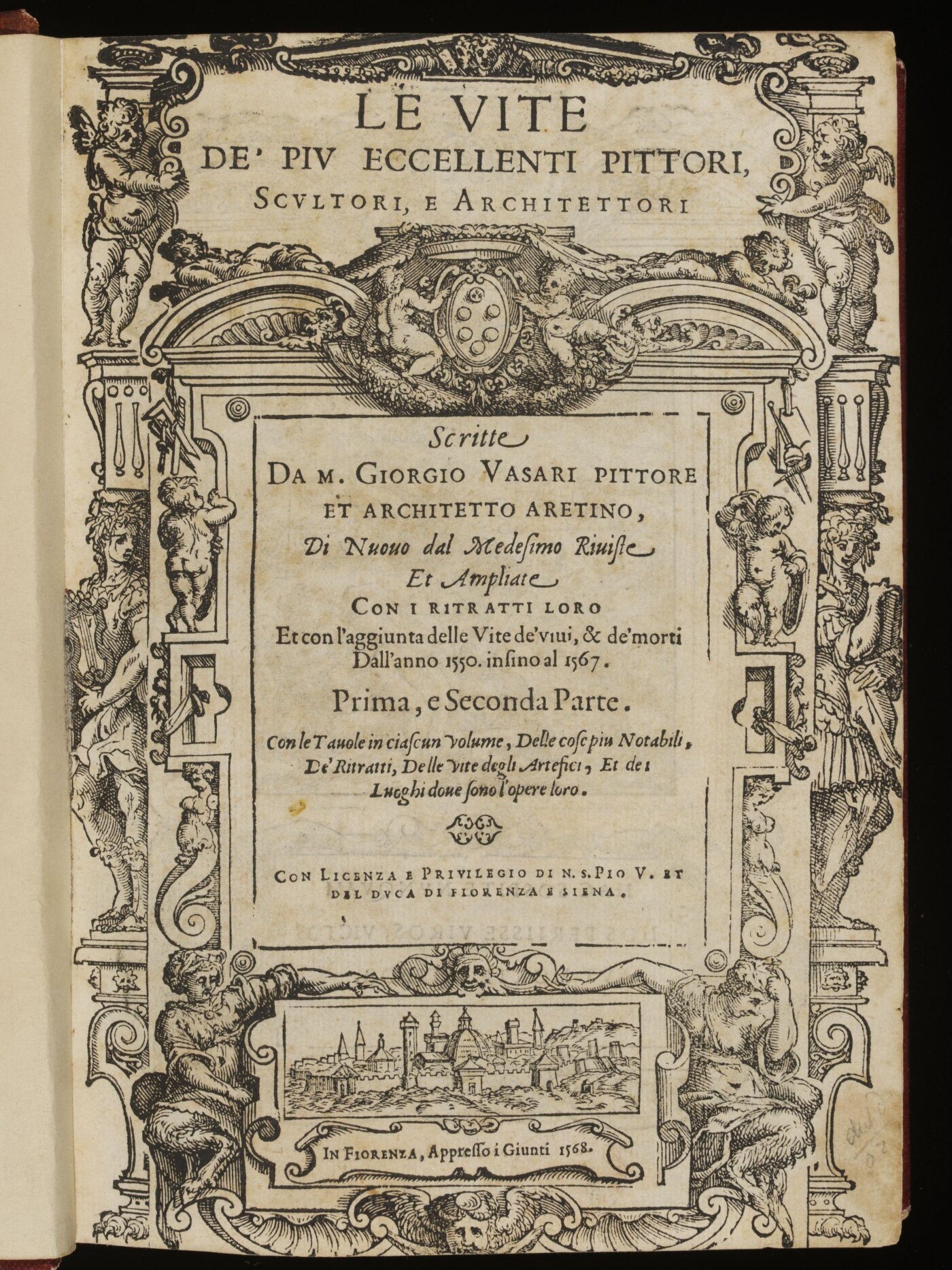

Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (Italian: Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori), often simply known as The Lives (Italian: Le Vite), is a series of artist biographies written by 16th-century Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, which is considered "perhaps the most famous, and even today the most-read work of the older literature of art",[1] "some of the Italian Renaissance's most influential writing on art",[2] and "the first important book on art history".[3]

"The Lives" redirects here. For other uses, see Lives.Author

Le Vite de più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri

Artist biographies

Torrentino (1550), Giunti (1568)

1550, enlarged and revised in 1568

1850

369 (1550), 686 (1568)

709.22

N6922 V4924

Vasari published the work in two editions with substantial differences between them; the first edition, two volumes, in 1550 and the second, three volumes, in 1568 (which is the one usually translated and referred to). One important change was the increased attention paid to Venetian art in the second edition, even though Vasari still was, and has ever since been, criticised for an excessive emphasis on the art of his native Florence.

Background[edit]

The writer Paolo Giovio expressed his desire to compose a treatise on contemporary artists at a party in the house of Cardinal Farnese, who asked Vasari to provide Giovio with as much relevant information as possible. Giovio instead yielded the project to Vasari.[4]

As the first Italian art historian, Vasari initiated the genre of an encyclopedia of artistic biographies that continues today. Vasari's work was first published in 1550 by Lorenzo Torrentino in Florence,[5] and dedicated to Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. It included a valuable treatise on the technical methods employed in the arts. It was partly rewritten and enlarged in 1568 and provided with woodcut portraits of artists (some conjectural).

The work has a consistent and notorious favour of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the new developments in Renaissance art – for example, the invention of engraving. Venetian art in particular, let alone other parts of Europe, is systematically ignored.[6] Between his first and second editions, Vasari visited Venice and the second edition gave more attention to Venetian art (finally including Titian) without achieving a neutral point of view. John Symonds claimed in 1899 that, "It is clear that Vasari often wrote with carelessness, confusing dates and places, and taking no pains to verify the truth of his assertions" (in regards to Vasari's life of Nicola Pisano), while acknowledging that, despite these shortcomings, it is one of the basic sources for information on the Renaissance in Italy.[7]

Vasari's biographies are interspersed with amusing gossip. Many of his anecdotes have the ring of truth, although likely inventions. Others are generic fictions, such as the tale of young Giotto painting a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue that the older master repeatedly tried to brush away, a genre tale that echoes anecdotes told of the Greek painter Apelles. He did not research archives for exact dates, as modern art historians do, and naturally his biographies are most dependable for the painters of his own generation and the immediately preceding one. Modern criticism—with all the new materials opened up by research—has corrected many of his traditional dates and attributions. The work is widely considered a classic even today, though it is widely agreed that it must be supplemented by modern scientific research.

Vasari includes a forty-two-page sketch of his own biography at the end of his Vite, and adds further details about himself and his family in his lives of Lazzaro Vasari and Francesco de' Rossi.

Italian

English