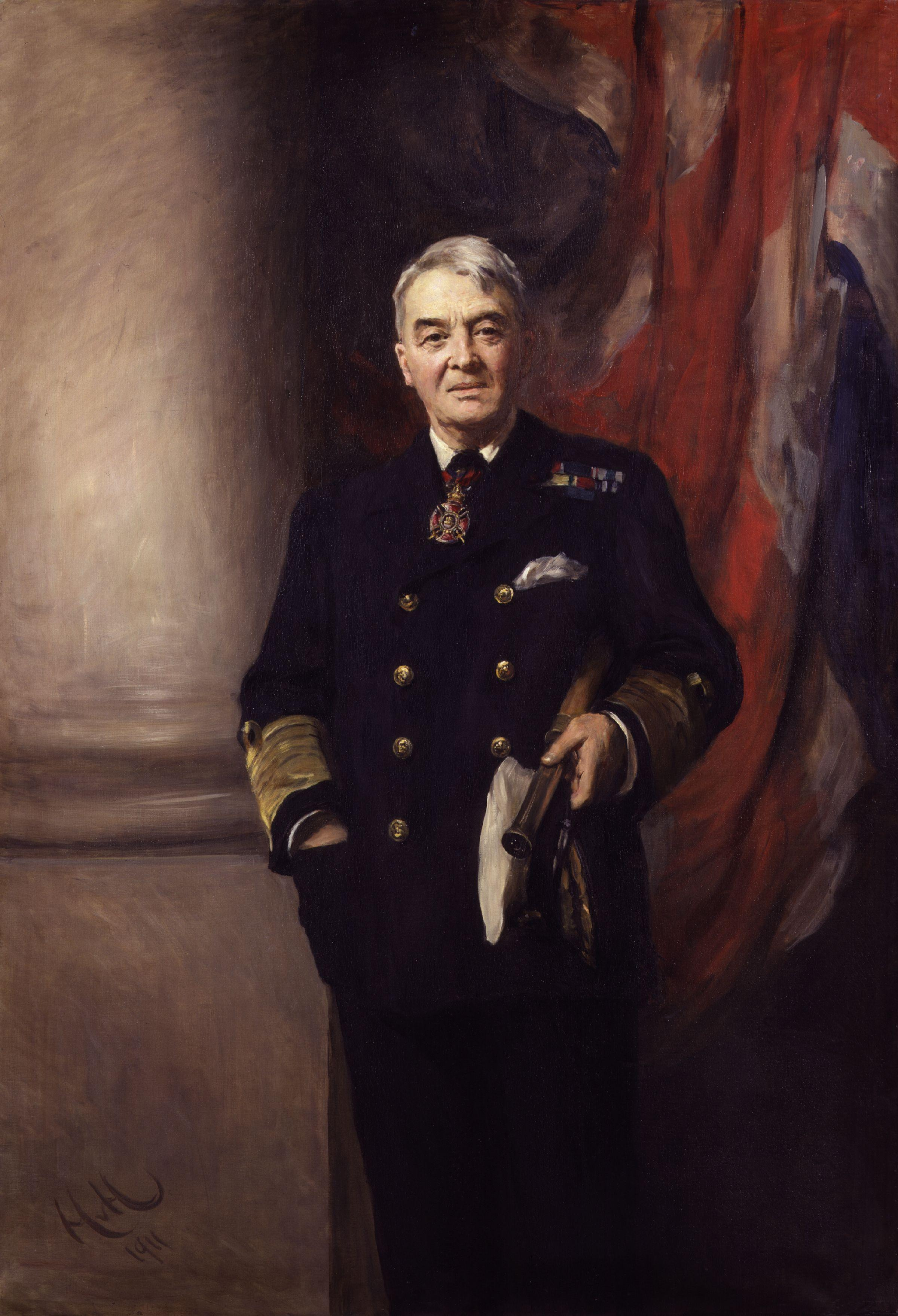

John Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher

Admiral of the Fleet John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher,[2] GCB, OM, GCVO (25 January 1841 – 10 July 1920), commonly known as Jacky or Jackie Fisher, was a British Admiral of the Fleet. With more than sixty years in the Royal Navy, his efforts to reform the service helped to usher in an era of modernisation which saw the supersession of wooden sailing ships armed with muzzle-loading cannon by steel-hulled battlecruisers, submarines and the first aircraft carriers.

"Admiral Fisher" redirects here. For other uses, see Admiral Fisher (disambiguation).

The Lord Fisher

Jacky

25 January 1841

Ramboda, Ceylon

10 July 1920 (aged 79)

London, England

United Kingdom

- 1854–1911

- 1914–1915

- First Sea Lord (1904–1910, 1914–1915)

- Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth (1903–1904)

- Second Naval Lord (1902–1903)

- Mediterranean Fleet (1899–1902)

- North America and West Indies Station (1897–1899)

- Third Naval Lord and Controller (1892–1897)

- Admiral Superintendent Portsmouth (1891)

- Director of Naval Ordnance (1886–1891)

- HMS Excellent (1883–1886)

- HMS Inflexible (1881–1882)

- HMS Northampton (1879–1881)

- HMS Bellerophon (1877–1878)

- HMS Vernon (1874–1877)

Fisher has a reputation as an innovator, strategist and developer of the navy rather than as a seagoing admiral involved in major battles, although in his career he experienced all these things. When appointed First Sea Lord in 1904 he removed 150 ships then on active service which were no longer useful and set about constructing modern replacements, developing a modern fleet prepared to meet Germany during the First World War.[3][4]

Fisher saw the need to improve the range, accuracy and rate-of-fire of naval gunnery, and became an early proponent of the use of the torpedo, which he believed would supersede big guns for use against ships. As Controller, he introduced torpedo-boat destroyers as a class of ship intended for defence against attack from torpedo boats or from submarines. As First Sea Lord he drove the construction of HMS Dreadnought, the first all-big-gun battleship, but he also believed that submarines would become increasingly important and urged their development. He became involved with the introduction of turbine engines to replace reciprocating engines, and with the introduction of oil fuelling to replace coal. He introduced daily baked bread on board ships, whereas when he entered the service it was customary to eat hard biscuits, frequently infested by biscuit beetles.[5]

He first officially retired from the Admiralty in 1910 on his 69th birthday, but became First Sea Lord again in November 1914. He resigned seven months later in frustration over Churchill's Gallipoli campaign, and then served as chairman of the Government's Board of Invention and Research until the end of the war.

Character and appearance[edit]

Fisher was five feet seven inches tall and stocky with a round face. In later years, some suggested that Fisher, born in Ceylon of British parents, had Asian ancestry due to his features and the yellow cast of his skin. However, his colour resulted from dysentery and malaria in middle life, which nearly caused his death. He had a fixed and compelling gaze when addressing someone, which gave little clue to his feelings. Fisher was energetic, ambitious, enthusiastic and clever. A shipmate described him as "easily the most interesting midshipman I ever met".[6] When addressing someone he could become carried away with the point he was seeking to make, and on one occasion, the King asked him to stop shaking his fist in his face.[7] He was considered a "man who demanded to be heard, and one who didn't suffer fools lightly".[8]

Throughout his life he was a religious man and attended church regularly when ashore. He had a passion for sermons and might attend two or three services in a day to hear them, which he would 'discuss afterwards with great animation'.[9] However, he was discreet in expressing his religious views because he feared public attention might hinder his professional career.[5][10]

He was not keen on sport, but he was a highly proficient dancer. Fisher employed his dancing skill later in life to charm a number of important ladies. He became interested in dancing in 1877 and insisted that the officers of his ship learn to dance. Fisher cancelled the leave of midshipmen who would not take part. He introduced the practice of junior officers dancing on deck when the band was playing for senior officers' wardroom dinners. This practice spread through the fleet. He broke with the then ball tradition of dancing with a different partner for each dance, instead adopting the scandalous habit of choosing one good dancer as his partner for the evening.[11] His ability to charm all comers of all social classes made up for his sometimes blunt or tactless comments.[12] He suffered from seasickness throughout his life.[13]

Fisher's aim was 'efficiency of the fleet and its instant readiness for war', which won him support amongst a certain kind of navy officer. He believed in advancing the most able, rather than the longest serving. This upset those he passed over. Thus, he divided the navy into those who approved of his innovations and those who did not. As he became older and more senior he also became more autocratic and commented, 'Anyone who opposes me, I crush'. He believed that nations fought wars for material gain, and that maintaining a strong navy deterred other nations from engaging it in battle, thus decreasing the likelihood of war: "On the British fleet rests the British Empire."[14] Fisher also believed that the risk of catastrophe in a sea battle was far greater than on land: a war could be lost or won in a day at sea, with no hope of replacing lost ships, but an army could be rebuilt quickly. When an arms race broke out between Germany and Britain to build larger navies, the German Kaiser commented, 'I admire Fisher, I say nothing against him. If I were in his place I should do all that he has done and I should do all that I know he has in mind to do'.[15]

First Sea Lord (1914–1915)[edit]

In October 1914 Lord Fisher was recalled as First Sea Lord, after Prince Louis of Battenberg had been forced to resign because of his German name. The Times reported that Fisher "was now entering the close of his 74th year but he was never younger or more vigorous". He resigned on 15 May 1915 amidst bitter arguments with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, over Gallipoli, causing Churchill's resignation too. Fisher was never entirely enthusiastic about the campaign—going back and forth in his support, to the consternation and frustration of members of the cabinet—and all in all preferred an amphibious attack on the German Baltic Sea coastline (the Baltic Project), even having the shallow-draft battlecruisers HMS Furious, HMS Glorious and HMS Courageous constructed for the purpose. As the Gallipoli campaign failed, relations with Churchill became increasingly acrimonious. One of Fisher's last contributions to naval construction was the projected HMS Incomparable, a mammoth battlecruiser which took the principles of the Courageous class another step further; mounting 20-inch guns, but still with minimal armour, Incomparable was never approved for construction.[124]

Fisher's resignation was initially not taken seriously: "Fisher is always resigning" commented the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith. However, when Fisher vacated his room at the Admiralty with the announced intention of retiring to Scotland, the Prime Minister sent him an order in the King's name to continue his duties. Senior naval officers and the press made appeals to the now elderly (74) First Sea Lord to remain in his position. Fisher responded with an eccentric letter to Asquith setting out six demands that would "guarantee the successful termination of the war". These would have given him unprecedented sole authority over the fleet, including all promotions and construction. After commenting that Fisher's behaviour indicated signs of mental aberration, Asquith responded with a brusque acceptance of Fisher's original resignation.[125]