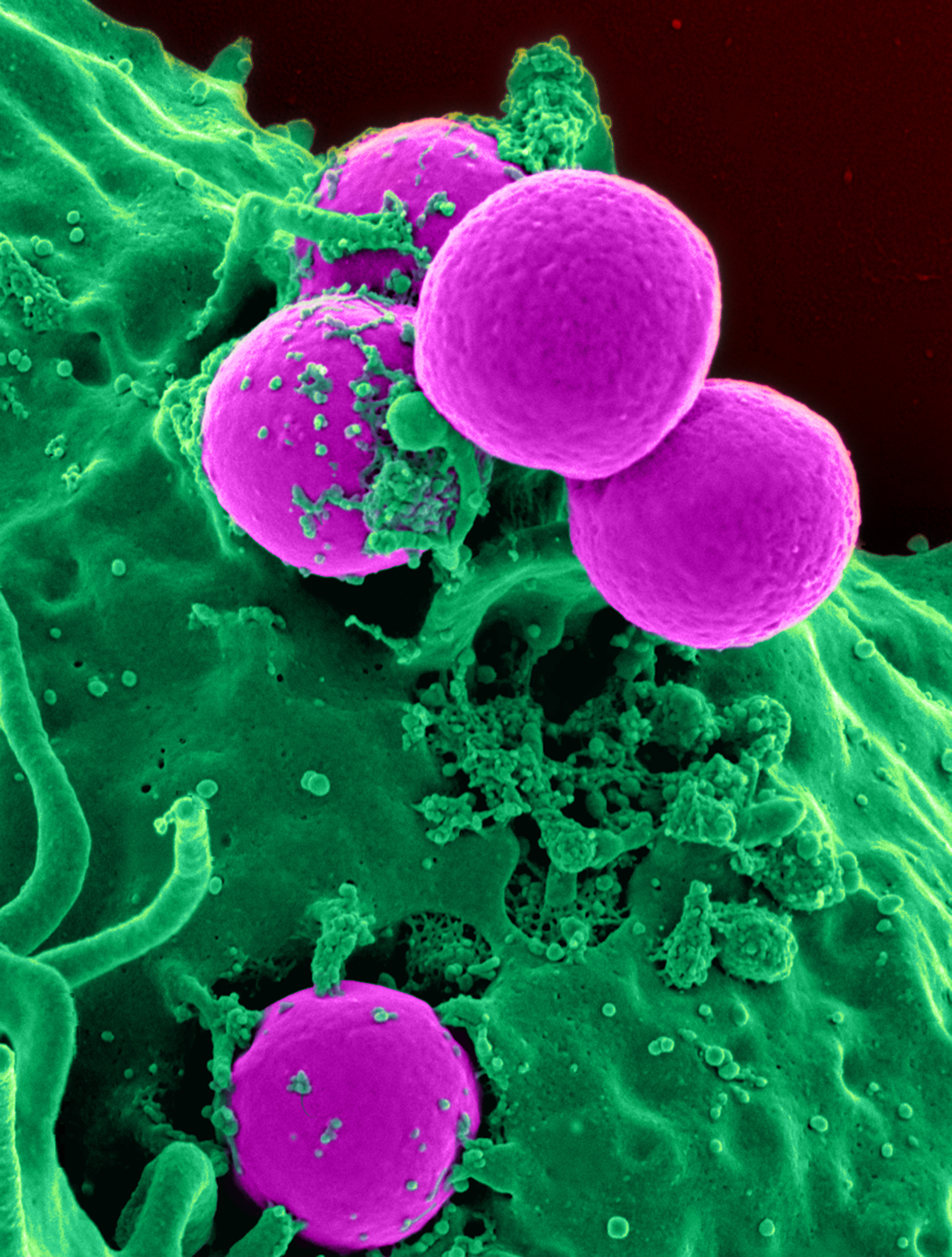

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a group of gram-positive bacteria that are genetically distinct from other strains of Staphylococcus aureus. MRSA is responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections in humans. It caused more than 100,000 deaths worldwide attributable to antimicrobial resistance in 2019.

"MRSA" redirects here. For other uses, see MRSA (disambiguation).

MRSA is any strain of S. aureus that has developed (through natural selection) or acquired (through horizontal gene transfer) a multiple drug resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Beta-lactam (β-lactam) antibiotics are a broad-spectrum group that include some penams (penicillin derivatives such as methicillin and oxacillin) and cephems such as the cephalosporins.[1] Strains unable to resist these antibiotics are classified as methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, or MSSA.

MRSA infection is common in hospitals, prisons, and nursing homes, where people with open wounds, invasive devices such as catheters, and weakened immune systems are at greater risk of healthcare-associated infection. MRSA began as a hospital-acquired infection but has become community-acquired, as well as livestock-acquired. The terms HA-MRSA (healthcare-associated or hospital-acquired MRSA), CA-MRSA (community-associated MRSA), and LA-MRSA (livestock-associated MRSA) reflect this.

Prevention[edit]

Screening[edit]

In health-care settings, isolating those with MRSA from those without the infection is one method to prevent transmission. Rapid culture and sensitivity testing and molecular testing identifies carriers and reduces infection rates.[71] It is especially important to test patients in these settings since 2% of people are carriers of MRSA, even though in many of these cases the bacteria reside in the nostril and the patient will not present any symptoms.[72]

MRSA can be identified by swabbing the nostrils and isolating the bacteria found there. Combined with extra sanitary measures for those in contact with infected people, swab screening people admitted to hospitals has been found to be effective in minimizing the spread of MRSA in hospitals in the United States, Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands.[73]

Handwashing[edit]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers suggestions for preventing the contraction and spread of MRSA infection which are applicable to those in community settings, including incarcerated populations, childcare center employees, and athletes. To prevent the spread of MRSA, the recommendations are to wash hands thoroughly and regularly using soap and water or an alcohol-based sanitizer. Additional recommendations are to keep wounds clean and covered, avoid contact with other people's wounds, avoid sharing personal items such as razors or towels, shower after exercising at athletic facilities, and shower before using swimming pools or whirlpools.[74]

Isolation[edit]

Excluding medical facilities, current US guidance does not require workers with MRSA infections to be routinely excluded from the general workplace.[75] The National Institutes of Health recommend that those with wound drainage that cannot be covered and contained with a clean, dry bandage and those who cannot maintain good hygiene practices be reassigned,[75] and patients with wound drainage should also automatically be put on "Contact Precaution," regardless of whether or not they have a known infection.[76] Workers with active infections are excluded from activities where skin-to-skin contact is likely to occur.[77] To prevent the spread of staphylococci or MRSA in the workplace, employers are encouraged to make available adequate facilities that support good hygiene. In addition, surface and equipment sanitizing should conform to Environmental Protection Agency-registered disinfectants.[75] In hospital settings, contact isolation can be stopped after one to three cultures come back negative.[78] Before the patient is cleared from isolation, it is advised that there is dedicated patient-care or single-use equipment for that particular patient. If this is not possible, the equipment must be properly disinfected before it is used on another patient.[76]

To prevent the spread of MRSA in the home, health departments recommend laundering materials that have come into contact with infected persons separately and with a dilute bleach solution; to reduce the bacterial load in one's nose and skin; and to clean and disinfect those things in the house that people regularly touch, such as sinks, tubs, kitchen counters, cell phones, light switches, doorknobs, phones, toilets, and computer keyboards.[79]

Restricting antibiotic use[edit]

Glycopeptides, cephalosporins, and in particular, quinolones are associated with an increased risk of colonisation of MRSA. Reducing use of antibiotic classes that promote MRSA colonisation, especially fluoroquinolones, is recommended in current guidelines.[12][25]

Public health considerations[edit]

Mathematical models describe one way in which a loss of infection control can occur after measures for screening and isolation seem to be effective for years, as happened in the UK. In the "search and destroy" strategy that was employed by all UK hospitals until the mid-1990s, all hospitalized people with MRSA were immediately isolated, and all staff were screened for MRSA and were prevented from working until they had completed a course of eradication therapy that was proven to work. Loss of control occurs because colonised people are discharged back into the community and then readmitted; when the number of colonised people in the community reaches a certain threshold, the "search and destroy" strategy is overwhelmed.[80] One of the few countries not to have been overwhelmed by MRSA is the Netherlands: an important part of the success of the Dutch strategy may have been to attempt eradication of carriage upon discharge from hospital.[81]

In the media[edit]

MRSA is frequently a media topic, especially if well-known personalities have announced that they have or have had the infection.[131][132][133] Word of outbreaks of infection appears regularly in newspapers and television news programs. A report on skin and soft-tissue infections in the Cook County jail in Chicago in 2004–05 demonstrated MRSA was the most common cause of these infections among those incarcerated there.[134] Lawsuits filed against those who are accused of infecting others with MRSA are also popular stories in the media.[135][136]

MRSA is the topic of radio programs,[137] television shows,[138][139][140] books,[141] and movies.[142]

Research[edit]

Various antibacterial chemical extracts from various species of the sweetgum tree (genus Liquidambar) have been investigated for their activity in inhibiting MRSA. Specifically, these are: cinnamic acid, cinnamyl cinnamate, ethyl cinnamate, benzyl cinnamate, styrene, vanillin, cinnamyl alcohol, 2-phenylpropyl alcohol, and 3-phenylpropyl cinnamate.[143]

The delivery of inhaled antibiotics along with systematic administration to treat MRSA are being developed. This may improve the outcomes of those with cystic fibrosis and other respiratory infections.[103] Phage therapy has been used for years in MRSA in eastern countries, and studies are ongoing in western countries.[144][145] Host-directed therapeutics, including host kinase inhibitors, as well as antimicrobial peptides are under study as adjunctive or alternative treatment for MRSA.[146][147][148]

A 2015 Cochrane systematic review aimed to assess the effectiveness of wearing gloves, gowns and masks to help stop the spread of MRSA in hospitals, however no eligible studies were identified for inclusion. The review authors concluded that there is a need for randomized controlled trials to be conducted to help determine if the use of gloves, gowns, and masks reduces the transmission of MRSA in hospitals.[149]