Maize

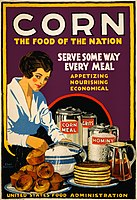

Maize /meɪz/ (Zea mays), also known as corn in North American and Australian English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native Americans planted it alongside beans and squashes in the Three Sisters polyculture. The leafy stalk of the plant gives rise to male inflorescences or tassels which produce pollen, and female inflorescences called ears. The ears yield grain, known as kernels or seeds. In modern commercial varieties, these are usually yellow or white; other varieties can be of many colors.

"Corn" redirects here. For other uses, see Corn (disambiguation) and Maize (disambiguation).

Maize relies on humans for its propagation. Since the Columbian exchange, it has become a staple food in many parts of the world, with the total production of maize surpassing that of wheat and rice. Much maize is used for animal feed, whether as grain or as the whole plant, which can either be baled or made into the more palatable silage. Sugar-rich varieties called sweet corn are grown for human consumption, while field corn varieties are used for animal feed, for uses such as cornmeal or masa, corn starch, corn syrup, pressing into corn oil, alcoholic beverages like bourbon whiskey, and as chemical feedstocks including ethanol and other biofuels.

Maize is cultivated throughout the world; a greater weight of maize is produced each year than any other grain. In 2020, world production was 1.1 billion tonnes. It is afflicted by many pests and diseases; two major insect pests, European corn borer and corn rootworms, have each caused annual losses of a billion dollars in the US. Modern plant breeding has greatly increased output and qualities such as nutrition, drought, and tolerance of pests and diseases. Much maize is now genetically modified.

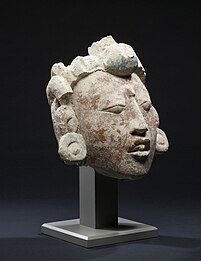

As a food, maize is used to make a wide variety of dishes including Mexican tortillas and tamales, Italian polenta, and American hominy grits. Maize protein is low in some essential amino acids, and the niacin it contains only becomes available if freed by alkali treatment. In Mesoamerica, maize is personified as a maize god and depicted in sculptures.

Names

The name maize derives from the Spanish form maíz of the Taíno mahis.[16] The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus used the common name maize as the species epithet in Zea mays.[17] The name Maize is preferred in formal, scientific, and international usage as a common name because it refers specifically to this one grain, unlike corn, which has a complex variety of meanings that vary by context and geographic region.[18] Most countries primarily use the term maize, and the name corn is used mainly in the United States and a handful of other English-speaking countries.[19][20] In countries that primarily use the term maize, the word "corn" may denote any cereal crop, varying geographically with the local staple,[21] such as wheat in England and oats in Scotland or Ireland.[18] The usage of corn for maize started as a shortening of "Indian corn" in 18th century North America.[22]

The historian of food Betty Fussell writes in an article on the history of the word "corn" in North America that "[t]o say the word "corn" is to plunge into the tragi-farcical mistranslations of language and history".[8] Similar to the British usage, the Spanish referred to maize as panizo, a generic term for cereal grains, as did Italians with the term polenta. The British later referred to maize as Turkey wheat, Turkey corn, or Indian corn; Fussell comments that "they meant not a place but a condition, a savage rather than a civilized grain".[8]

International groups such as the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International consider maize the preferred common name.[23] The word maize is used by the UN's FAO,[24] and in the names of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center of Mexico, the Indian Institute of Maize Research,[25] the Maize Association of Australia,[26] the National Maize Association of Nigeria,[27] the National Maize Association of Ghana,[28] the Maize Trust of South Africa,[29] and the Zimbabwe Seed Maize Association.[30]

Maize is a tall annual grass with a single stem, ranging in height from 1.2 m (4 ft) to 4 m (13 ft).[31] The long narrow leaves arise from the nodes or joints, alternately on opposite sides on the stalk.[31] Maize is monoecious, with separate male and female flowers on the same plant.[31] At the top of the stem is the tassel, an inflorescence of male flowers; their anthers release pollen, which is dispersed by wind.[31] Like other pollen, it is an allergen, but most of it falls within a few meters of the tassel and the risk is largely restricted to farm workers.[32]

The female inflorescence, some way down the stem from the tassel, is first seen as a silk, a bundle of soft tubular hairs, one for the carpel in each female flower, which develops into a kernel (often called a seed. Botanically, as in all grasses, it is a fruit, fused with the seed coat to form a caryopsis[33]) when it is pollinated.[31] A whole female inflorescence develops into an ear or corncob, enveloped by multiple leafy layers or husks.[31]

The ear leaf is the leaf most closely associated with a particular developing ear. This leaf and those above it contribute over three quarters of the carbohydrate (starch) that fills the grain.[34]

The grains are usually yellow or white in modern varieties; other varieties have orange, red, brown, blue, purple, or black grains. They are arranged in 8 to 32 rows around the cob; there can be up to 1200 grains on a large cob.[6] Yellow maizes derive their color from carotenoids; red maizes are colored by anthocyanins and phlobaphenes; and orange and green varieties may contain combinations of these pigments.[35]

Maize has short-day photoperiodism, meaning that it requires nights of a certain length to flower. Flowering further requires enough warm days above 10 °C (50 °F). The control of flowering is set genetically; the physiological mechanism involves the phytochrome system. Tropical cultivars can be problematic if grown in higher latitudes, as the longer days can make the plants grow tall instead of setting seed before winter comes. On the other hand, growing tall rapidly could be convenient for producing biofuel.[31]

Immature maize shoots accumulate a powerful antibiotic substance, 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA), which provides a measure of protection against a wide range of pests.[36] Because of its shallow roots, maize is susceptible to droughts, intolerant of nutrient-deficient soils, and prone to being uprooted by severe winds.[37]

Breeding

Conventional breeding

Maize breeding in prehistory resulted in large plants producing large ears. Modern breeding began with individuals who selected highly productive varieties in their fields and then sold seed to other farmers. James L. Reid was one of the earliest and most successful, developing Reid's Yellow Dent in the 1860s. These early efforts were based on mass selection (a row of plants is grown from seeds of one parent), the choosing of plants after pollination (which means that only the female parents are known). Later breeding efforts included ear to row selection (C. G. Hopkins c. 1896), hybrids made from selected inbred lines (G. H. Shull, 1909), and the highly successful double cross hybrids using four inbred lines (D. F. Jones c. 1918, 1922). University-supported breeding programs were especially important in developing and introducing modern hybrids.[48]

Since the 1940s, the best strains of maize have been first-generation hybrids made from inbred strains that have been optimized for specific traits, such as yield, nutrition, drought, pest and disease tolerance. Both conventional cross-breeding and genetic engineering have succeeded in increasing output and reducing the need for cropland, pesticides, water and fertilizer. There is conflicting evidence to support the hypothesis that maize yield potential has increased over the past few decades. This suggests that changes in yield potential are associated with leaf angle, lodging resistance, tolerance of high plant density, disease/pest tolerance, and other agronomic traits rather than increase of yield potential per individual plant.[49]

Certain varieties of maize have been bred to produce many ears; these are the source of the "baby corn" used as a vegetable in Asian cuisine.[50][51] A fast-flowering variety named mini-maize was developed to aid scientific research, as multiple generations can be obtained in a single year.[52] One strain called olotón has evolved a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing microbes, which provides the plant with 29%–82% of its nitrogen.[53] The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) operates a conventional breeding program to provide optimized strains. The program began in the 1980s.[54] Hybrid seeds are distributed in Africa by its Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa project.[55]

Tropical landraces remain an important and underused source of resistance alleles – both those for disease and for herbivores. Such alleles can then be introgressed into productive varieties.[56] Rare alleles for this purpose were discovered by Dao and Sood, both in 2014.[56] In 2018, Zerka Rashid of CIMMYT used its association mapping panel, developed for tropical drought tolerance traits. to find new genomic regions providing sorghum downy mildew resistance, and to further characterize known differentially methylated regions.[57]

Agronomy

Growing

Because it is cold-intolerant, in the temperate zones maize must be planted in the spring. Its root system is generally shallow, so the plant is dependent on soil moisture. As a plant that uses C4 carbon fixation, maize is a considerably more water-efficient crop than plants that use C3 carbon fixation such as alfalfa and soybeans. Maize is most sensitive to drought at the time of silk emergence, when the flowers are ready for pollination. In the United States, a good harvest was traditionally predicted if the maize was "knee-high by the Fourth of July", although modern hybrids generally exceed this growth rate. Maize used for silage is harvested while the plant is green and the fruit immature. Sweet corn is harvested in the "milk stage", after pollination but before starch has formed, between late summer and early to mid-autumn. Field maize is left in the field until very late in the autumn to thoroughly dry the grain, and may, in fact, sometimes not be harvested until winter or even early spring. The importance of sufficient soil moisture is shown in many parts of Africa, where periodic drought regularly causes maize crop failure and consequent famine. Although it is grown mainly in wet, hot climates, it can thrive in cold, hot, dry or wet conditions, meaning that it is an extremely versatile crop.[71]

Maize was planted by the Native Americans in small hills of soil, in the polyculture system called the Three Sisters.[72] Maize provided support for beans; the beans provided nitrogen derived from nitrogen-fixing rhizobia bacteria which live on the roots of beans and other legumes; and squashes provided ground cover to stop weeds and inhibit evaporation by providing shade over the soil.[73]

Top Maize producers

360.3 (31%)

260.7 (22.43%)

104 (8.95%)

58.4 (5.02%)

30.3 (2.61%)

30.2 (2.6%)

27.4 (2.36%)

22.5 (1.94%)

15.3 (1.32%)

13.9 (1.2%)

1162.4

Many pests can affect maize growth and development, including invertebrates, weeds, and pathogens.[83][84]

Maize is susceptible to a large number of fungal, bacterial, and viral plant diseases. Those of economic importance include diseases of the leaf, smuts such as corn smut, ear rots and stalk rots.[85] Northern corn leaf blight damages maize throughout its range, whereas banded leaf and sheath blight is a problem in Asia.[86][87] Some fungal diseases of maize produce potentially dangerous mycotoxins such as aflatoxin.[60] In the United States, major diseases include tar spot, bacterial leaf streak, gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight, and Goss's wilt; in 2022, the most damaging disease was tar spot, which caused losses of 116.8 million bushels.[88]

Maize sustains a billion dollars' worth of losses annually in the US from each of two major insect pests, namely the European corn borer or ECB (Ostrinia nubilalis) and corn rootworms (Diabrotica spp) western corn rootworm, northern corn rootworm, and southern corn rootworm.[89][90][91] Another serious pest is the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda).[92]

The maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais) is a serious pest of stored grain.[93] The Northern armyworm, Oriental armyworm or Rice ear-cutting caterpillar (Mythimna separata) is a major pest of maize in Asia.[94]

Nematodes too are pests of maize. It is likely that every maize plant harbors some nematode parasites, and populations of Pratylenchus lesion nematodes in the roots can be "enormous". The effects on the plants include stunting, sometimes of whole fields, sometimes in patches, especially when there is also water stress and poor control of weeds.[95]

Many plants, both monocots (grasses) such as Echinochloa crus-galli (barnyard grass) and dicots (forbs) such as Chenopodium and Amaranthus may compete with maize and reduce crop yields. Control may involve mechanical weed removal, flame weeding, or herbicides.[96]

Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz)

360 kJ (86 kcal)

5.7 g

6.26 g

2 g

0.023 g

0.129 g

0.129 g

0.348 g

0.137 g

0.067 g

0.026 g

0.150 g

0.123 g

0.185 g

0.131 g

0.089 g

0.295 g

0.244 g

0.636 g

0.127 g

0.292 g

0.153 g

Quantity

Quantity

Quantity

75.96 g

In Mesoamerica, maize is seen as a vital force, personified as a maize god, usually female.[119] In the United States, maize ears are carved into column capitals in the United States Capitol building.[120] The Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota, uses cobs and ears of colored maize to implement a mural design that is recycled annually.[121] The concrete Field of Corn sculpture in Dublin, Ohio depicts hundreds of ears of corn in a grassy field.[122] A maize stalk with two ripe ears is depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 1 lipa coin, minted since 1993.[123]

![Production of maize (2019)[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Production_of_maize_%282019%29.svg/561px-Production_of_maize_%282019%29.svg.png)

![Maize (pink strip) is the second most widely produced primary crop, after sugarcane, and the first among grain crops.[82]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/49/World_Production_Of_Primary_Crops%2C_Main_Commodities.svg/403px-World_Production_Of_Primary_Crops%2C_Main_Commodities.svg.png)