Mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland in humans and other mammals that produces milk to feed young offspring. Mammals get their name from the Latin word mamma, "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, humans and chimpanzees), the udder in ruminants (for example, cows, goats, sheep, and deer), and the dugs of other animals (for example, dogs and cats). Lactorrhea, the occasional production of milk by the glands, can occur in any mammal, but in most mammals, lactation, the production of enough milk for nursing, occurs only in phenotypic females who have gestated in recent months or years. It is directed by hormonal guidance from sex steroids. In a few mammalian species, male lactation can occur. With humans, male lactation can occur only under specific circumstances.

"Mammary" redirects here. For the mountain in Alaska, see Mammary Peak.Mammary gland

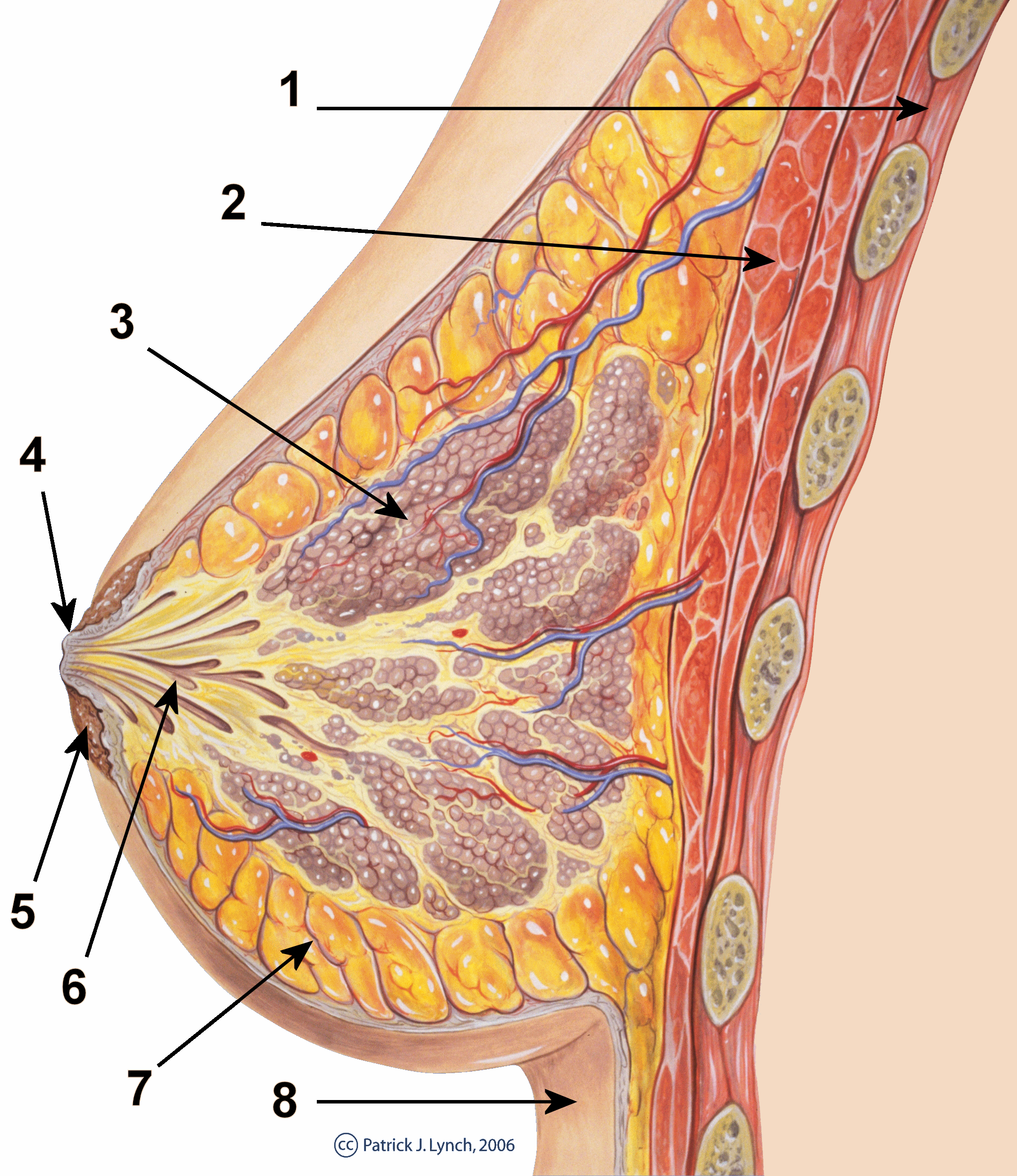

Supraclavicular nerves

Intercostal nerves[2]

(lateral and medial branches)

Mammals are divided into 3 groups: prototherians, metatherians, and eutherians. In the case of prototherians, both males and females have functional mammary glands, but their mammary glands are without nipples. These mammary glands are modified sebaceous glands. Concerning metatherians and eutherians, only females have functional mammary glands. Their mammary glands can be termed as breasts or udders. In the case of breasts, each mammary gland has its own nipple (e.g., human mammary glands). In the case of udders, pairs of mammary glands comprise a single mass, with more than one nipple (or teat) hanging from it. For instance, cows and buffalo udders have two pairs of mammary glands and four teats, whereas sheep and goat udders have one pair of mammary glands with two teats protruding from the udder. Each gland produces milk for a single teat. These mammary glands are modified sweat glands.

Physiology[edit]

Hormonal control[edit]

Lactiferous duct development occurs in females in response to circulating hormones. First development is frequently seen during pre- and postnatal stages, and later during puberty. Estrogen promotes branching differentiation,[37] whereas in males testosterone inhibits it. A mature duct tree reaching the limit of the fat pad of the mammary gland comes into being by bifurcation of duct terminal end buds (TEB), secondary branches sprouting from primary ducts[7][38] and proper duct lumen formation. These processes are tightly modulated by components of mammary epithelial ECM interacting with systemic hormones and local secreting factors. However, for each mechanism the epithelial cells' "niche" can be delicately unique with different membrane receptor profiles and basement membrane thickness from specific branching area to area, so as to regulate cell growth or differentiation sub-locally.[39] Important players include beta-1 integrin, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), laminin-1/5, collagen-IV, matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs), heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and others. Elevated circulating level of growth hormone and estrogen get to multipotent cap cells on TEB tips through a thin, leaky layer of basement membrane. These hormones promote specific gene expression. Hence cap cells can differentiate into myoepithelial and luminal (duct) epithelial cells, and the increased amount of activated MMPs can degrade surrounding ECM helping duct buds to reach further in the fat pads.[40][41] On the other hand, basement membrane along the mature mammary ducts is thicker, with strong adhesion to epithelial cells via binding to integrin and non-integrin receptors. When side branches develop, it is a much more "pushing-forward" working process including extending through myoepithelial cells, degrading basement membrane and then invading into a periductal layer of fibrous stromal tissue.[7] Degraded basement membrane fragments (laminin-5) roles to lead the way of mammary epithelial cells migration.[42] Whereas, laminin-1 interacts with non-integrin receptor dystroglycan negatively regulates this side branching process in case of cancer.[43] These complex "Yin-yang" balancing crosstalks between mammary ECM and epithelial cells "instruct" healthy mammary gland development until adult.

There is preliminary evidence that soybean intake mildly stimulates the breast glands in pre- and postmenopausal women.[44]

Pregnancy[edit]

Secretory alveoli develop mainly in pregnancy, when rising levels of prolactin, estrogen, and progesterone cause further branching, together with an increase in adipose tissue and a richer blood flow. In gestation, serum progesterone remains at a stably high concentration so signaling through its receptor is continuously activated. As one of the transcribed genes, Wnts secreted from mammary epithelial cells act paracrinely to induce more neighboring cells' branching.[45][46] When the lactiferous duct tree is almost ready, "leaves" alveoli are differentiated from luminal epithelial cells and added at the end of each branch. In late pregnancy and for the first few days after giving birth, colostrum is secreted. Milk secretion (lactation) begins a few days later due to reduction in circulating progesterone and the presence of another important hormone prolactin, which mediates further alveologenesis, milk protein production, and regulates osmotic balance and tight junction function. Laminin and collagen in myoepithelial basement membrane interacting with beta-1 integrin on epithelial surface again, is essential in this process.[47][48] Their binding ensures correct placement of prolactin receptors on the basal lateral side of alveoli cells and directional secretion of milk into lactiferous ducts.[47][48] Suckling of the baby causes release of the hormone oxytocin, which stimulates contraction of the myoepithelial cells. In this combined control from ECM and systemic hormones, milk secretion can be reciprocally amplified so as to provide enough nutrition for the baby.

Weaning[edit]

During weaning, decreased prolactin, missing mechanical stimulation (baby suckling), and changes in osmotic balance caused by milk stasis and leaking of tight junctions cause cessation of milk production. It is the (passive) process of a child or animal ceasing to be dependent on the mother for nourishment. In some species there is complete or partial involution of alveolar structures after weaning, in humans there is only partial involution and the level of involution in humans appears to be highly individual. The glands in the breast do secrete fluid also in nonlactating women.[49] In some other species (such as cows), all alveoli and secretory duct structures collapse by programmed cell death (apoptosis) and autophagy for lack of growth promoting factors either from the ECM or circulating hormones.[50][51] At the same time, apoptosis of blood capillary endothelial cells speeds up the regression of lactation ductal beds. Shrinkage of the mammary duct tree and ECM remodeling by various proteinase is under the control of somatostatin and other growth inhibiting hormones and local factors.[52] This major structural change leads loose fat tissue to fill the empty space afterward. But a functional lactiferous duct tree can be formed again when a female is pregnant again.

Clinical significance[edit]

Tumorigenesis in mammary glands can be induced biochemically by abnormal expression level of circulating hormones or local ECM components,[53] or from a mechanical change in the tension of mammary stroma.[54] Under either of the two circumstances, mammary epithelial cells would grow out of control and eventually result in cancer. Almost all instances of breast cancer originate in the lobules or ducts of the mammary glands.

Other mammals[edit]

General[edit]

The breasts of female humans vary from most other mammals that tend to have less conspicuous mammary glands. The number and positioning of mammary glands varies widely in different mammals. The protruding teats and accompanying glands can be located anywhere along the two milk lines. In general most mammals develop mammary glands in pairs along these lines, with a number approximating the number of young typically birthed at a time. The number of teats varies from 2 (in most primates) to 18 (in pigs). The Virginia opossum has 13, one of the few mammals with an odd number.[55][56] The following table lists the number and position of teats and glands found in a range of mammals: