Manned Orbiting Laboratory

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was part of the United States Air Force (USAF) human spaceflight program in the 1960s. The project was developed from early USAF concepts of crewed space stations as reconnaissance satellites, and was a successor to the canceled Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar military reconnaissance space plane. Plans for the MOL evolved into a single-use laboratory, for which crews would be launched on 30-day missions, and return to Earth using a Gemini B spacecraft derived from NASA's Gemini spacecraft and launched with the laboratory.

Station statistics

2

Canceled

14,476 kg (31,914 lb)

21.92 m (71.9 ft)

3.05 m (10.0 ft)

11.3 m3 (400 cu ft)

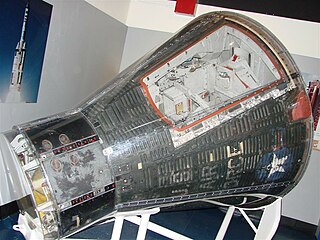

The MOL program was announced to the public on 10 December 1963 as an inhabited platform to demonstrate the utility of putting people in space for military missions; its reconnaissance satellite mission was a secret black project. Seventeen astronauts were selected for the program, including Major Robert H. Lawrence Jr., the first African-American astronaut. The prime contractor for the spacecraft was McDonnell Aircraft Corporation; the laboratory was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company. The Gemini B was externally similar to NASA's Gemini spacecraft, although it underwent several modifications, including the addition of a circular hatch through the heat shield, which allowed passage between the spacecraft and the laboratory. Vandenberg Space Launch Complex 6 (SLC-6) was developed to permit launches into polar orbit.

As the 1960s progressed, the Vietnam War competed with the MOL for funds, and resultant budget cuts repeatedly postponed its first operational flight. At the same time, automated systems rapidly improved, narrowing the benefits of a crewed space platform over an automated one. A single uncrewed test flight of the Gemini B spacecraft was conducted on 3 November 1966, but the MOL was canceled in June 1969 without any crewed missions being flown.

Seven of the astronauts transferred to NASA in August 1969 as NASA Astronaut Group 7, all of whom eventually flew in space on the Space Shuttle between 1981 and 1985. The Titan IIIM rocket developed for the MOL never flew, but its UA1207 solid rocket boosters were used on the Titan IV, and the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster was based on materials, processes and designs developed for them. NASA spacesuits were derived from the MOL ones, MOL's waste management system flew in space on Skylab, and NASA Earth Science used other MOL equipment. SLC-6 was refurbished, but plans to have military Space Shuttle launches from there were abandoned in the wake of the January 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

Planned operations[edit]

Reconnaissance[edit]

From the MOL's regular 280-kilometer (150 nmi) orbit, the main camera had a circular field of view 2,700 meters (9,000 ft) across, although at top magnification it was more like 1,300 meters (4,200 ft). This was much smaller than many of the targets that the NRO was interested in, such as air bases, shipyards and missile ranges. The astronauts would search for targets using the tracking and acquisition telescopes, which had a circular view about 12.0 km (6.5 nmi) across, with a resolution of about 9.1 meters (30 ft). The main camera would focus on the most important targets, providing a very high resolution image. The aim was to have the most interesting part of the target in the center of the image; due to the optics used, the image would not be as sharp around the edges.[67]

While surveillance targets were pre-programmed and the camera could operate automatically, astronauts could decide target priority for photographing. By avoiding cloudy areas and identifying more interesting subjects (an open missile silo instead of a closed one, for example), they would save film,[68] the major limitation, since it had to be returned in the small Gemini B spacecraft. In cloudy areas like Moscow, it was estimated that the MOL would be 45 percent more efficient in its use of film than an automated satellite system through the ability to react to cloud cover, but for sunnier areas like the Tyuratam missile complex, this might be no more than 15 percent. The selective targeting afforded by human-guided surveillance would be more efficient than that obtained by robotic satellites. Of the 159 KH-7 Gambit photographs of the Tyuratam area, only 9 percent showed missiles on the launch pads, and of 77 photographs of missile silos, only 21 percent were with the doors open. The analysts identified 60 MOL targets in the complex. Only two or three could be photographed on each pass, but astronauts could select the most interesting ones, and photograph them with greater resolution than KH-7 Gambit.[67]

The Air Force expected that an improved version of the MOL space station, known as Block II, expected to be available for the sixth crewed flight in July 1974, would add image transmission and geodetic system targeting. Astronauts would perform infrared, multispectral, and ultraviolet astronomy when they had time during an extended mission duration on twice-annual flights.[69] After Block II, the MOL program managers hoped to build larger, permanent facilities. A planning document depicted 12-man and 40-man stations, both with self-defense capability. It described the 40-man, Y-shaped station as a "spaceborne command post" in synchronous orbit. With the "key requirement – post attack survivability", the station would be capable of "Strategic/tactical decision making" during a general war.[69][70]

Public response[edit]

With the 1966 Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament approaching, there were concerns about how the MOL was viewed by the international community. The United States insisted that the MOL was in line with the 17 October 1963 United Nations General Assembly resolution that the exploration and use of outer space should be used only "for the betterment of mankind". To allay Soviet fears that the MOL would carry nuclear weapons, the State Department suggested that Soviet officials be permitted to inspect it for them before launch, but Brown opposed this on security grounds.[105]

Public debate of the merits of the MOL program was hobbled by its semi-secret nature. Writing about the MOL as an outsider in 1967, Leonard E. Schwartz, a consultant to the Directorate for Scientific Affairs of the OECD, noted that the United States already had SAMOS satellites for reconnaissance and Vela satellites for surveillance of nuclear explosions, but without knowing their capabilities or those of MOL, could not evaluate the actual costs or benefits of the program.[106]

Publicly, the Air Force vaguely described the MOL as "an effective space building block of very substantial potential, a space resource capable of growth to follow-on tasks".[107] "On completion", Brady declared in 1965, "we will have configured, acquired, and most important, conducted a manned military space operation thereby acquiring the crews, experience and equipment that will, if required, allow the Air Force to move into the near-earth space environment in an orderly and effective manner".[108]

The Soviet Union commissioned the development of its own military space station, Almaz. This project was initiated by chief-designer Vladimir Chelomey on 12 October 1964, but it was Johnson's announcement of the MOL program on 25 August 1965 that led to the Almaz project receiving official endorsement and funding on 27 October 1965.[109] Three Almaz space stations flew as Salyut space stations between 1973 and 1976 before the crewed Almaz program was canceled in 1978.[110][111]