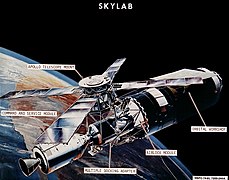

Skylab

Skylab was the United States' first space station, launched by NASA,[3] occupied for about 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. It was operated by three trios of astronaut crews: Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4. Operations included an orbital workshop, a solar observatory, Earth observation and hundreds of experiments. Skylab's orbit eventually decayed and it disintegrated in the atmosphere on July 11, 1979, scattering debris across the Indian Ocean and Western Australia.

For other uses, see Skylab (disambiguation).Station statistics

Skylab

3 per mission (9 total)

May 14, 1973

17:30:00 UTC (50 years ago)

Modified Saturn V

July 11, 1979

16:37:00 UTC

Deorbited

168,750 pounds (76,540 kg)[1]

w/o Apollo CSM

82.4 feet (25.1 m)

w/o Apollo CSM

55.8 feet (17.0 m)

w/ one solar panel

36.3 feet (11.1 m)

w/ telescope mount

21.67 feet (6.61 m)

12,417 cubic feet (351.6 m3)

5.0 pounds per square inch (34 kPa) Oxygen 74%, nitrogen 26%[2]

269.7 miles (434.0 km)

274.6 miles (441.9 km)

50.0°

93.4 minutes

15.4

2249 days (6.6 years)

171 days

34,981

~890,000,000 mi (1,400,000,000 km)

There were two types of gyroscopes on Skylab. Control-moment gyroscopes (CMG) could physically move the station, and rate gyroscopes measured the rate of rotation to find its orientation.[78] The CMG helped provide the fine pointing needed by the Apollo Telescope Mount, and to resist various forces that can change the station's orientation.[79]

Some of the forces acting on Skylab that the pointing system needed to resist:[79]

Skylab was the first large spacecraft to use big gyroscopes, capable of controlling its attitude.[80] The control could also be used to help point the instruments.[80] The gyroscopes took about ten hours to get spun up if they were turned off.[81] There was also a thruster system to control Skylab's attitude.[81] There were 9 rate-gyroscope sensors, 3 for each axis.[81] These were sensors that fed their output to the Skylab digital computer.[81] Two of three were active and their input was averaged, while the third was a backup.[81] From NASA SP-400 Skylab, Our First Space Station, "each Skylab control-moment gyroscope consisted of a motor-driven rotor, electronics assembly, and power inverter assembly. The 21-inch (530 mm) diameter rotor weighed 155 pounds (70 kg) and rotated at approximately 8950 revolutions per minute".[82]

There were three control moment gyroscopes on Skylab, but only two were required to maintain pointing.[82] The control and sensor gyroscopes were part of a system that help detect and control the orientation of the station in space.[82] Other sensors that helped with this were a Sun tracker and a star tracker.[82] The sensors fed data to the main computer, which could then use the control gyroscopes and or the thruster system to keep Skylab pointed as desired.[82]

There was a variety of hand-held and fixed experiments that used various types of film. In addition to the instruments in the ATM solar observatory, 35 and 70 mm film cameras were carried on board. An analog TV camera was carried that recorded video electronically. These electronic signals could be recorded to magnetic tape or be transmitted to Earth by radio signal.

It was determined that film would fog up to due to radiation over the course of the mission.[73] To prevent this, film was stored in vaults.[73]

Personal (hand-held) camera equipment:[90]

Film for the DAC was contained in DAC film magazines, which contained up to 140 feet (42.7 m) of film.[92] At 24 frames per second this was enough for 4 minutes of filming, with progressively longer film times with lower frame rates such as 16 minutes at 6 frames per second.[91] The film had to be loaded or unloaded from the DAC in a photographic dark room.[91]

Experiment S190B was the Actron Earth Terrain Camera.[90]

The S190A was the Multispectral Photographic Camera:[90]

There was also a Polaroid SX-70 instant camera,[96] and a pair of Leitz Trinovid 10 × 40 binoculars modified for use in space to aid in Earth observations.[90]

The SX-70 was used to take pictures of the Extreme Ultraviolet monitor by Dr. Garriot, as the monitor provided a live video feed of the solar corona in ultraviolet light as observed by Skylab solar observatory instruments located in the Apollo Telescope Mount.[97]

Skylab was controlled in part by a digital computer system, and one of its main jobs was to control the pointing of the station; pointing was especially important for its solar power collection and observatory functions.[98] The computer consisted of two actual computers, a primary and a secondary. The system ran several thousand words of code, which was also backed up on the Memory Load Unit (MLU).[98] The two computers were linked to each other and various input and output items by the workshop computer interface.[99] Operations could be switched from the primary to the backup, which were the same design, either automatically if errors were detected, by the Skylab crew, or from the ground.[98]

The Skylab computer was a space-hardened and customized version of the TC-1 computer, a version of the IBM System/4 Pi, itself based on the System 360 computer.[98] The TC-1 had a 16,000-word memory based on ferrite memory cores, while the MLU was a read-only tape drive that contained a backup of the main computer programs.[98] The tape drive would take 11 seconds to upload the backup of the software program to a main computer.[100] The TC-1 used 16-bit words and the central processor came from the 4Pi computer.[100] There was a 16k and an 8k version of the software program.[101]

The computer had a mass of 100 pounds (45.4 kg), and consumed about ten percent of the station's electrical power.[98][99]

After launch the computer is what the controllers on the ground communicated with to control the station's orientation.[102] When the sun-shield was torn off the ground staff had to balance solar heating with electrical production.[102] On March 6, 1978, the computer system was re-activated by NASA to control the re-entry.[103]

The system had a user interface that consisted of a display, ten buttons, and a three-position switch.[104] Because the numbers were in octal (base-8), it only had numbers zero to seven (8 keys), and the other two keys were enter and clear.[104] The display could show minutes and seconds which would count down to orbital benchmarks, or it could display keystrokes when using the interface.[104] The interface could be used to change the software program.[104] The user interface was called the Digital Address System (DAS) and could send commands to the computer's command system. The command system could also get commands from the ground.[101]

For personal computing needs Skylab crews were equipped with models of the then new hand-held electronic scientific calculator, which was used in place of slide-rules used on prior space missions as the primary personal computer. The model used was the Hewlett Packard HP 35.[105] Some slide rules continued in use aboard Skylab, and a circular slide rule was at the workstation.[106]

A full-size 1G training mock-up once used for astronaut training is located at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center visitor's center in Houston, Texas.

Another training mockup, originally used at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), is at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Originally displayed indoors, it was subsequently stored outdoors for several years to make room for other exhibits. To mark the 40th anniversary of the Skylab program, the Orbital Workshop portion of the trainer was restored and moved into the Davidson Center in 2013.[159][160]

Program cost[edit]

From 1966 to 1974, the Skylab program cost a total of US$2.2 billion, (equivalent to $17 billion in 2023). As its three three-person crews spent 510 total man-days in space, each man-day cost approximately US$20 million, compared to US$7.5 million for the International Space Station.[167]

The documentary Searching for Skylab was released online in March 2019. It was written and directed by Dwight Steven-Boniecki and was partly crowdfunded.[168]

The alternate history Apple TV+ original series For All Mankind depicts the use of the space station in the first episode of the second season, surviving to the 1980s and coexisting with the Space Shuttle program in the alternate timeline.[169]

In the 2011 film Skylab, a family gathers in France and waits for the station to fall out of orbit. It was directed by Julie Delpy.[170]

The 2021 Indian film Skylab depicts fictitious incidents in a Telangana village preceding the disintegration of the space station.[171]

A minor storyline of the 1986 film Dogs in Space is an attempt by characters of the Melbourne household to fabricate pieces of Skylab and win a radio station's competition to locate debris from the space station as it fell to earth in Australia.