Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

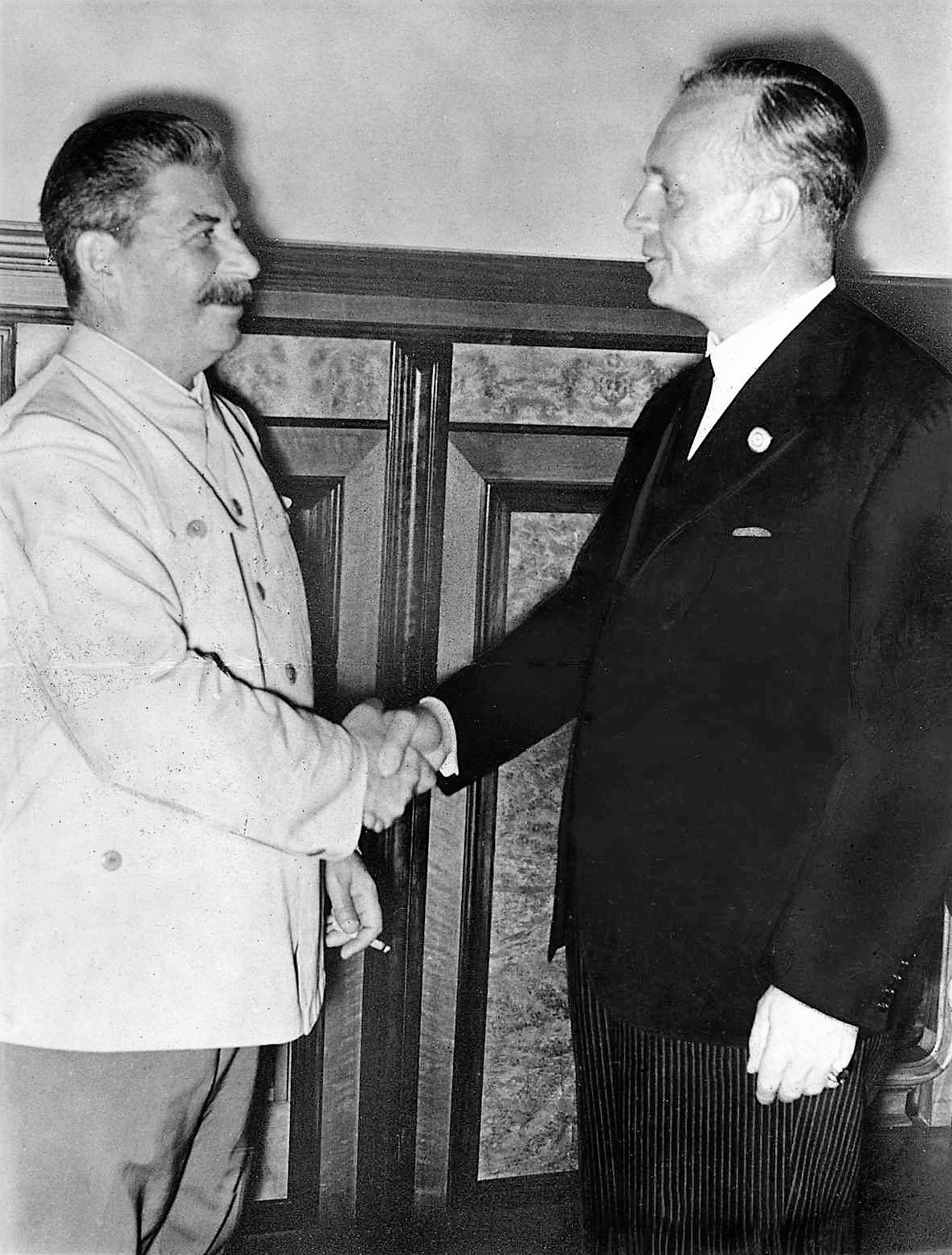

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,[1][2] was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union with a secret protocol that partitioned Central and Eastern Europe between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov.[3] Unofficially, it has also been referred to as the Hitler–Stalin Pact[4][5] and the Nazi–Soviet Pact.[6]

"German–Soviet pact" redirects here. For the Weimar-era German–Soviet non-aggression pact, see Treaty of Berlin (1926).Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics[b]

23 August 1939

- German

- Russian

The treaty was the culmination of negotiations for an economic agreement between the USSR and Nazi Germany which the Soviets used to obtain a political agreement – see Nazi–Soviet economic relations (1934–1941) § 1938–1939 deal discussions. On 22 August, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to finalize the treaty, which the Soviets had sought before with Britain and France. The Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, signed the next day, guaranteed peace between the parties and was a commitment neither government would aid or ally itself with an enemy of the other. In addition to the publicly announced stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included the Secret Protocol, which defined the borders of Soviet and German spheres of influence across Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland. The secret protocol also recognized the interest of Lithuania in the Vilnius region, and Germany declared its complete uninterest in Bessarabia. The rumoured existence of the Secret Protocol was proven only when it was made public during the Nuremberg trials.[7]

Soon after the pact, Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September, one day after a Soviet–Japanese ceasefire came into effect after the Battles of Khalkhin Gol,[8] and one day after the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union approved the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[9] After the invasions, the new border between the two countries was confirmed by the supplementary protocol of the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty. In March 1940, parts of the Karelia and Salla regions in Finland were annexed by the Soviet Union following the Winter War. The Soviet annexation of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and parts of Romania (Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region) followed. The Soviets used concern for ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians as a pretext for their invasion of Poland. Stalin's invasion of Bukovina in 1940 violated the pact, since it went beyond the Soviet sphere of influence that had been agreed with the Axis.[10]

The territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union following the 1939 Soviet invasion east of the Curzon line remained in the Soviet Union after the war and are now in Ukraine and Belarus. Vilnius was given to Lithuania. Only Podlaskie and a small part of Galicia east of the San River, around Przemyśl, were returned to Poland. Of all the other territories annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939–1940, those detached from Finland (Western Karelia, Petsamo), Estonia (Estonian Ingria and Petseri County) and Latvia (Abrene) remain part of Russia, the successor state to the Russian SFSR and the Soviet Union after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The territories annexed from Romania were also integrated into the Soviet Union (such as the Moldavian SSR, or oblasts of the Ukrainian SSR). The core of Bessarabia now forms Moldova. Northern Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region now form the Chernivtsi Oblast of Ukraine. Southern Bessarabia is part of the Odessa Oblast, which is also now in Ukraine.

The pact was terminated on 22 June 1941, when Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union, in pursuit of the ideological goal of Lebensraum.[11] The Anglo-Soviet Agreement succeeded it. After the war, Ribbentrop was convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials and executed. Molotov died in 1986.

Remembrance and response[edit]

The pact was a taboo subject in the postwar Soviet Union.[296] In December 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union condemned the pact and its secret protocol as "legally deficient and invalid".[297] In modern Russia, the pact is often portrayed positively or neutrally by the pro-government propaganda; for example, Russian textbooks tend to describe the pact as a defensive measure, not as one aiming at territorial expansion.[296] In 2009, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that "there are grounds to condemn the Pact",[298] but described it in 2014 as "necessary for Russia's survival".[299][300] Accusations that cast doubt on the positive portrayal of the USSR's role in World War II have been seen as highly problematic for the modern Russian state, which sees Russia's victory in the war as one of "the most venerated pillars of state ideology", which legitimises the current government and its policies.[301][302] In February 2021, the State Duma voted in favor of a law to punish the dissemination of "fake news" regarding the Soviet Union's role in World War II, including claiming that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union held equal responsibility due to the pact.[303]

In 2009, the European Parliament proclaimed 23 August, the anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, to be commemorated with dignity and impartiality.[304] In connection with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe parliamentary resolution condemned both communism and fascism for starting World War II and called for a day of remembrance for victims of both Stalinism and Nazism on 23 August.[305] In response to the resolution, Russian lawmakers threatened the OSCE with "harsh consequences".[305][306] A similar resolution was passed by the European Parliament a decade later, blaming the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop pact for the outbreak of war in Europe and again leading to criticism by Russian authorities.[301][302][307]