Multicellular organism

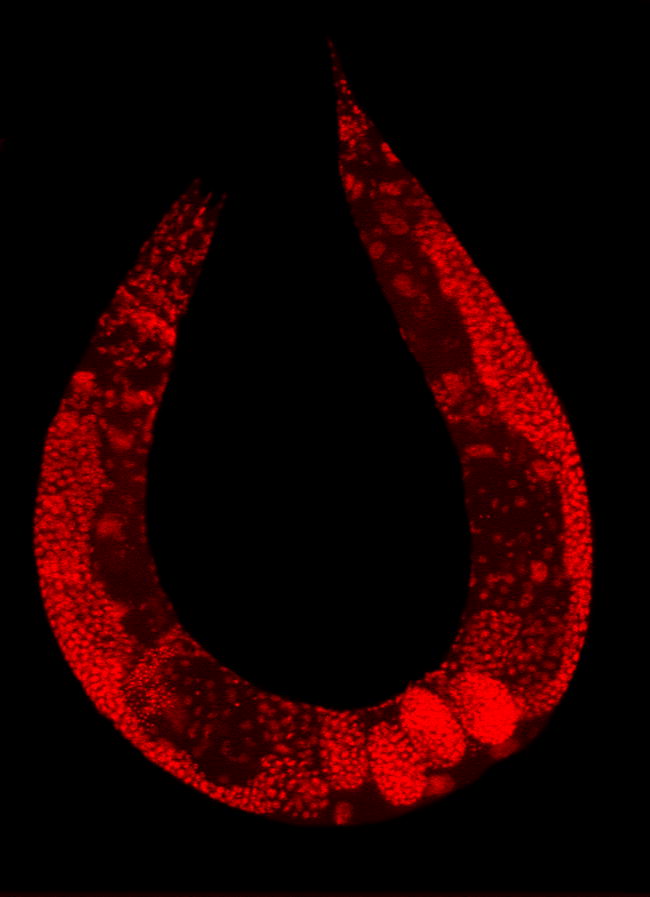

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.[1] All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and partially multicellular, like slime molds and social amoebae such as the genus Dictyostelium.[2][3]

Multicellular organisms arise in various ways, for example by cell division or by aggregation of many single cells.[4][3] Colonial organisms are the result of many identical individuals joining together to form a colony. However, it can often be hard to separate colonial protists from true multicellular organisms, because the two concepts are not distinct; colonial protists have been dubbed "pluricellular" rather than "multicellular".[5][6] There are also macroscopic organisms that are multinucleate though technically unicellular, such as the Xenophyophorea that can reach 20 cm.

Evolutionary history[edit]

Occurrence[edit]

Multicellularity has evolved independently at least 25 times in eukaryotes,[7][8] and also in some prokaryotes, like cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, actinomycetes, Magnetoglobus multicellularis or Methanosarcina.[3] However, complex multicellular organisms evolved only in six eukaryotic groups: animals, symbiomycotan fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and land plants.[9] It evolved repeatedly for Chloroplastida (green algae and land plants), once for animals, once for brown algae, three times in the fungi (chytrids, ascomycetes, and basidiomycetes)[10] and perhaps several times for slime molds and red algae.[11] The first evidence of multicellular organization, which is when unicellular organisms coordinate behaviors and may be an evolutionary precursor to true multicellularity, is from cyanobacteria-like organisms that lived 3.0–3.5 billion years ago.[7] To reproduce, true multicellular organisms must solve the problem of regenerating a whole organism from germ cells (i.e., sperm and egg cells), an issue that is studied in evolutionary developmental biology. Animals have evolved a considerable diversity of cell types in a multicellular body (100–150 different cell types), compared with 10–20 in plants and fungi.[12]

Loss of multicellularity[edit]

Loss of multicellularity occurred in some groups.[13] Fungi are predominantly multicellular, though early diverging lineages are largely unicellular (e.g., Microsporidia) and there have been numerous reversions to unicellularity across fungi (e.g., Saccharomycotina, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts).[14][15] It may also have occurred in some red algae (e.g., Porphyridium), but they may be primitively unicellular.[16] Loss of multicellularity is also considered probable in some green algae (e.g., Chlorella vulgaris and some Ulvophyceae).[17][18] In other groups, generally parasites, a reduction of multicellularity occurred, in the number or types of cells (e.g., the myxozoans, multicellular organisms, earlier thought to be unicellular, are probably extremely reduced cnidarians).[19]

Cancer[edit]

Multicellular organisms, especially long-living animals, face the challenge of cancer, which occurs when cells fail to regulate their growth within the normal program of development. Changes in tissue morphology can be observed during this process. Cancer in animals (metazoans) has often been described as a loss of multicellularity and an atavistic reversion towards a unicellular-like state.[20] Many genes responsible for the establishment of multicellularity that originated around the appearance of metazoans are deregulated in cancer cells, including genes that control cell differentiation, adhesion and cell-to-cell communication.[21][22] There is a discussion about the possibility of existence of cancer in other multicellular organisms[23][24] or even in protozoa.[25] For example, plant galls have been characterized as tumors,[26] but some authors argue that plants do not develop cancer.[27]

Separation of somatic and germ cells[edit]

In some multicellular groups, which are called Weismannists, a separation between a sterile somatic cell line and a germ cell line evolved. However, Weismannist development is relatively rare (e.g., vertebrates, arthropods, Volvox), as a great part of species have the capacity for somatic embryogenesis (e.g., land plants, most algae, many invertebrates).[28][10]

It is impossible to know what happened when single cells evolved into multicellular organisms hundreds of millions of years ago. However, we can identify mutations that can turn single-celled organisms into multicellular ones. This would demonstrate the possibility of such an event. Unicellular species can relatively easily acquire mutations that make them attach to each other—the first step towards multicellularity. Multiple normally unicellular species have been evolved to exhibit such early steps:

C. reinhartii normally starts as a motile single-celled propagule; this single cell asexually reproduces by undergoing 2–5 rounds of mitosis as a small clump of non-motile cells, then all cells become single-celled propagules and the clump dissolves. With a few generations under Paramecium predation, the "clump" becomes a persistent structure: only some cells become propagules. Some populations go further and evolved multi-celled propagules: instead of peeling off single cells from the clump, the clump now reproduces by peeling off smaller clumps.[56]

Advantages[edit]

Multicellularity allows an organism to exceed the size limits normally imposed by diffusion: single cells with increased size have a decreased surface-to-volume ratio and have difficulty absorbing sufficient nutrients and transporting them throughout the cell. Multicellular organisms thus have the competitive advantages of an increase in size without its limitations. They can have longer lifespans as they can continue living when individual cells die. Multicellularity also permits increasing complexity by allowing differentiation of cell types within one organism.

Whether all of these can be seen as advantages however is debatable: The vast majority of living organisms are single celled, and even in terms of biomass, single celled organisms are far more successful than animals, although not plants.[57]

Rather than seeing traits such as longer lifespans and greater size as an advantage, many biologists see these only as examples of diversity, with associated tradeoffs.

Gene expression changes in the transition from uni- to multicellularity[edit]

During the evolutionary transition from unicellular organisms to multicellular organisms, the expression of genes associated with reproduction and survival likely changed.[58] In the unicellular state, genes associated with reproduction and survival are expressed in a way that enhances the fitness of individual cells, but after the transition to multicellularity, the pattern of expression of these genes must have substantially changed so that individual cells become more specialized in their function relative to reproduction and survival.[58] As the multicellular organism emerged, gene expression patterns became compartmentalized between cells that specialized in reproduction (germline cells) and those that specialized in survival (somatic cells). As the transition progressed, cells that specialized tended to lose their own individuality and would no longer be able to both survive and reproduce outside the context of the group.[58]