Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophies (MD) are a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of rare neuromuscular diseases that cause progressive weakness and breakdown of skeletal muscles over time.[1] The disorders differ as to which muscles are primarily affected, the degree of weakness, how fast they worsen, and when symptoms begin.[1] Some types are also associated with problems in other organs.[2]

Muscular dystrophy

Increasing weakening, breakdown of skeletal muscles, trouble walking[1][2]

Chronic[1]

Pharmacotherapy, physical therapy, braces, corrective surgery, assisted ventilation[1][2]

Depends on the particular disorder[1]

Over 30 different disorders are classified as muscular dystrophies.[1][2] Of those, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) accounts for approximately 50% of cases and affects males beginning around the age of four.[1] Other relatively common muscular dystrophies include Becker muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophy,[1] whereas limb–girdle muscular dystrophy and congenital muscular dystrophy are themselves groups of several – usually extremely rare – genetic disorders.

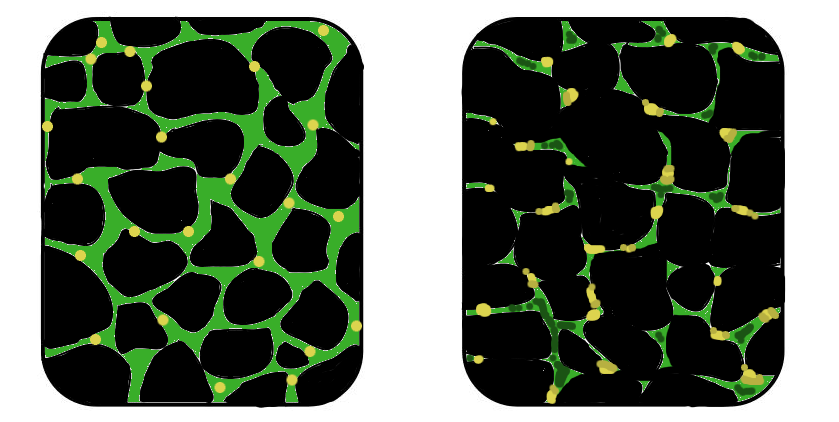

Muscular dystrophies are caused by mutations in genes, usually those involved in making muscle proteins.[2] The muscle protein, dystrophin, is in most muscle cells and works to strengthen the muscle fibers and protect them from injury as muscles contract and relax.[3] It links the muscle membrane to the thin muscular filaments within the cell. Dystrophin is an integral part of the muscular structure. An absence of dystrophin can cause impairments: healthy muscle tissue can be replaced by fibrous tissue and fat, causing an inability to generate force.[4] Respiratory and cardiac complications can occur as well. These mutations are either inherited from parents or may occur spontaneously during early development.[2] Muscular dystrophies may be X-linked recessive, autosomal recessive, or autosomal dominant.[2] Diagnosis often involves blood tests and genetic testing.[2]

There is no cure for any disorder from the muscular dystrophy group.[1] Several drugs designed to address the root cause are currently available including gene therapy (Elevidys), and antisense drugs (Ataluren, Eteplirsen etc.).[2] Other medications used include glucocorticoids (Deflazacort, Vamorolone); calcium channel blockers (Diltiazem); to slow skeletal and cardiac muscle degeneration, anticonvulsants to control seizures and some muscle activity, and Histone deacetylase inhibitors (Givinostat) to delay damage to dying muscle cells.[1] Physical therapy, braces, and corrective surgery may help with some symptoms[1] while assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[2]

Outcomes depend on the specific type of disorder.[1] Many affected people will eventually become unable to walk[2] and Duchenne muscular dystrophy in particular is associated with shortened life expectancy.

Muscular dystrophy was first described in the 1830s by Charles Bell.[2] The word "dystrophy" comes from the Greek dys, meaning "no, un-" and troph- meaning "nourish".[2]

Causes[edit]

The majority of muscular dystrophies are inherited; the different muscular dystrophies follow various inheritance patterns (X-linked, autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant). In a small percentage of patients, the disorder may have been caused by a de novo (spontaneous) mutation.[6][7]

Prognosis[edit]

Prognosis depends on the individual form of muscular dystrophy. Some dystrophies cause progressive weakness and loss of muscle function, which may result in severe physical disability and a life-threatening deterioration of respiratory muscles or heart. Other dystrophies do not affect life expectancy and only cause relatively mild impairment.[2]

History[edit]

In the 1860s, descriptions of boys who grew progressively weaker, lost the ability to walk, and died at an early age became more prominent in medical journals. In the following decade,[30] French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne gave a comprehensive account of the most common and severe form of the disease, which now carries his name – Duchenne MD.[31]

Society and culture[edit]

In 1966 in the US and Canada, Jerry Lewis and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) began the annual Labor Day telecast The Jerry Lewis Telethon, significant in raising awareness of muscular dystrophy in North America. Disability rights advocates, however, have criticized the telethon for portraying those living with the disease as deserving pity rather than respect.[32]

On December 18, 2001, the MD CARE Act was signed into law in the US; it amends the Public Health Service Act to provide research for the various muscular dystrophies. This law also established the Muscular Dystrophy Coordinating Committee to help focus research efforts through a coherent research strategy.[33][34]