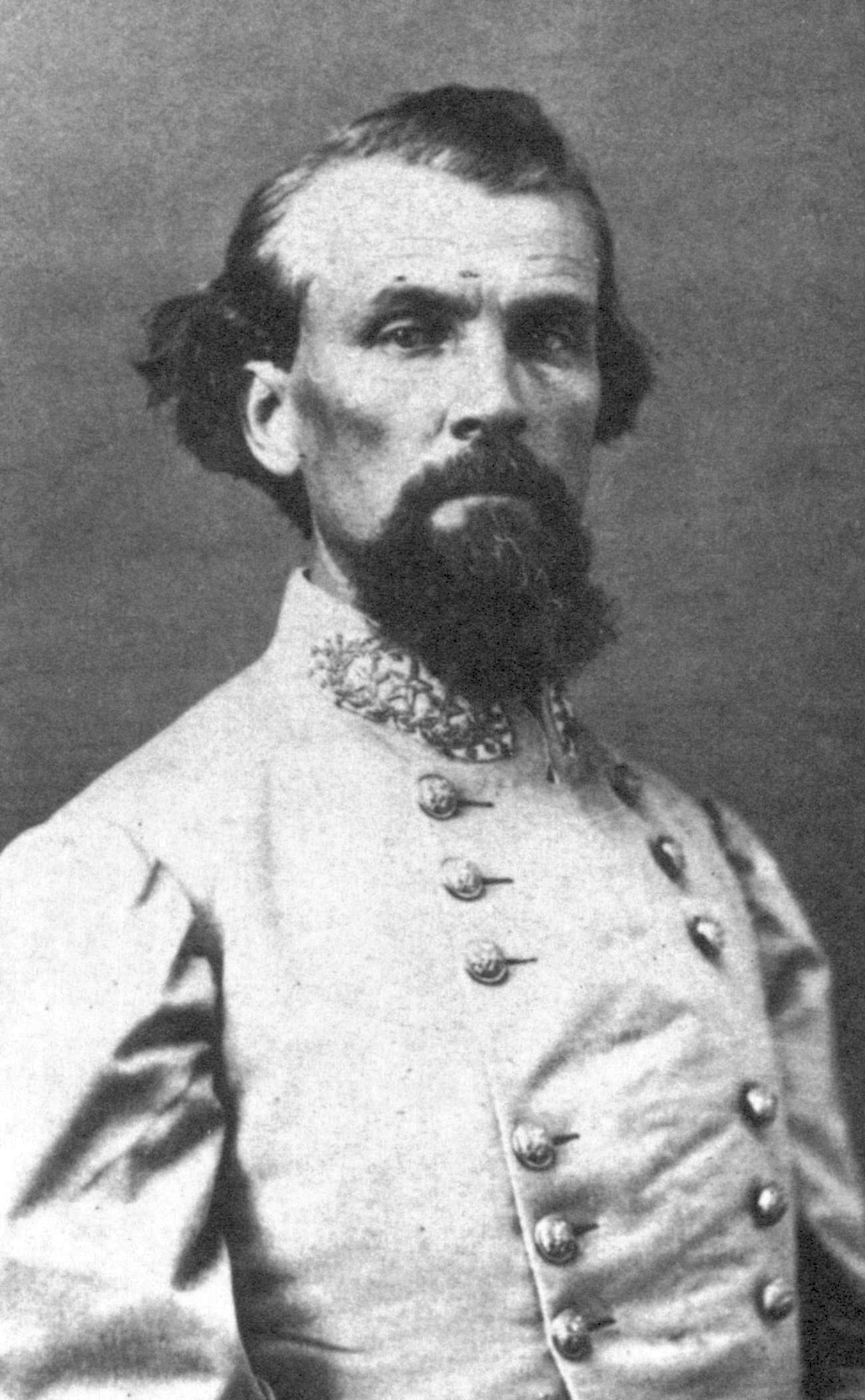

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877) was a Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and was later the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869.

This article is about the Confederate general. For other uses, see Nathan Bedford Forrest (disambiguation).

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest

July 13, 1821

Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S.

October 29, 1877 (aged 56)

Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.

1861–1865

- White's Company "E"

- Tennessee Mounted Rifles

- (7th Tennessee Cavalry)

- Nathan Forrest II (grandson)

- Nathan Forrest III (great grandson)

Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a cotton plantation owner, horse and cattle trader, real estate broker, and slave trader. In June 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army and became one of the few soldiers during the war to enlist as a private and be promoted to general without previous military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a corps and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle". He used his cavalry troops as mounted infantry and often deployed artillery as the lead in battle, thus helping to "revolutionize cavalry tactics".[3][4] "Forrest never failed to destroy the military reputation of the Federal commanders encountered by him" succinctly characterizes the perception held by opponents, reporters, and historians alike, of his martial tactical achievements.[5] While scholars generally acknowledge Forrest's skills and acumen as a cavalry leader and military strategist, he is a controversial figure in U.S. history for prewar slave trading, his role in the massacre of several hundred U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Pillow, a majority of them black, and his postwar leadership of the Klan.

In April 1864, in what has been called "one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history",[6] troops under Forrest's command at the Battle of Fort Pillow massacred hundreds of surrendered troops, composed of black soldiers and white Tennessean Southern Unionists fighting for the United States. Forrest was blamed for the slaughter in the U.S. press, and this news may have strengthened the United States's resolve to win the war. Forrest's level of responsibility for the massacre is still debated by historians.[7]

Forrest, who was a Freemason,[8] joined the Ku Klux Klan in 1867 (two years after its founding) and was elected its first Grand Wizard. The group was a loose collection of local factions throughout the former Confederacy that used violence or threats of violence to maintain white control over the newly enfranchised, formerly enslaved people. The Klan, with Forrest at the lead, suppressed the voting rights of blacks in the Southern United States through violence and intimidation during the elections of 1868. In 1869, Forrest expressed disillusionment with the lack of discipline in the white supremacist terrorist group across the South,[9] and issued a letter ordering the dissolution of the Ku Klux Klan as well as the destruction of its costumes; he then withdrew from the organization.[10] In the last years of his life, Forrest denied being a Klan member[11] and, disturbed by anti-black violence, made statements in support of racial harmony and black dignity.[12]

In June 2021, the remains of Forrest and his wife were exhumed from Health Sciences Park, where they had been buried for over 100 years, and where a monument of him once stood. They were later reburied in Columbia, Tennessee. In July 2021, Tennessee officials voted to move Forrest's bust from the State Capitol to the Tennessee State Museum.[13]

American Civil War[edit]

Early cavalry command[edit]

After the Civil War broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee from his Mississippi ventures and enlisted in the Confederate States Army (CSA) on June 14, 1861. He reported for training at Fort Wright near Randolph, Tennessee,[58] joining Captain Josiah White's cavalry company, the Tennessee Mounted Rifles (Seventh Tennessee Cavalry), as a private along with his youngest brother and 15-year-old son. Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest offered to buy horses and equipment with his own money for a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers.[28][59]

His superior officers and Governor of Tennessee Isham G. Harris were surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier, especially since significant planters were exempted from service. They commissioned him as a lieutenant colonel and authorized him to recruit and train a battalion of Confederate mounted rangers.[60] In October 1861, Forrest was given command of a regiment, the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Though Forrest had no prior formal military training or experience, he had exhibited leadership and soon proved he could successfully employ military tactics.[33][61]

Public debate surrounded Tennessee's decision to join the Confederacy, and both the Confederate and United States armies recruited soldiers from the state. Over 100,000 men from Tennessee served with the Confederacy, and over 31,000 served with the U.S. Army.[62] Forrest posted advertisements to join his regiment, with the slogan, "Let's have some fun and kill some Yankees!".[63] Forrest's command included his Escort Company (his "Special Forces"), for which he selected the best soldiers available. This unit, which varied in size from 40 to 90 men, constituted the elite of his cavalry.[64]

Notes

Bibliography

Further reading