American Indian boarding schools

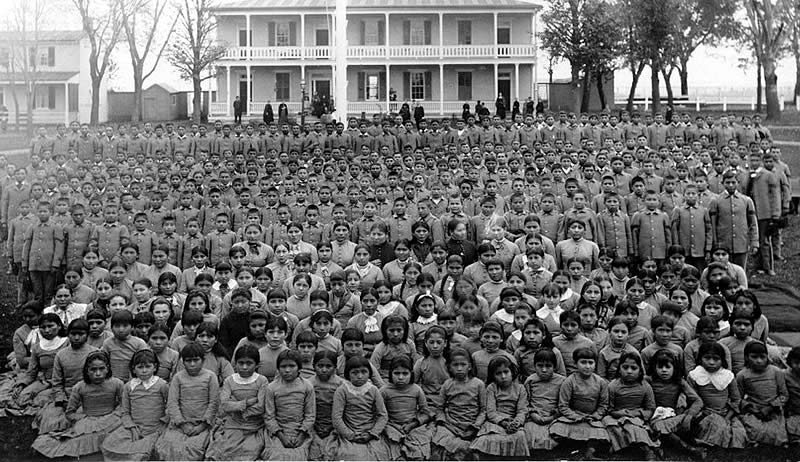

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into Anglo-American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion.[1] At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations,[2] especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid Church denominations to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools. Similarly to schools that taught speakers of immigrant languages, the curriculum was rooted in linguistic imperialism, the English only movement, and forced assimilation enforced by corporal punishment. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

This article is about the system in the United States. For the residential school system in Canada, see Canadian Indian residential school system. For other uses, see Indian school (disambiguation).

Children were typically immersed in the Anglo-American culture of the upper class. Schools forced removal of indigenous cultural signifiers: cutting the children's hair, having them wear American-style uniforms, forbidding them from speaking their mother tongues, and replacing their tribal names with English language names (saints' names under some religious orders) for use at the schools, as part of assimilation and to Christianize them.[3] The schools were usually harsh, especially for younger children who had been forcibly separated from their families and forced to abandon their Native American identities and cultures. Children sometimes died in the school system due to infectious disease.[3] Investigations of the later 20th century revealed cases of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.[4]

Summarizing recent scholarship from Native perspectives, Dr. Julie Davis said:

Since those years, tribal nations have carried out political activism and gained legislation and federal policy that gives them the power to decide how to use federal education funds, how they educate their children, and the authority to establish their own community-based schools. Tribes have also founded numerous tribal colleges and universities on reservations. Tribal control over their schools has been supported by federal legislation and changing practices by the BIA. By 2007, most of the boarding schools had been closed down, and the number of Native American children in boarding schools had declined to 9,500.[6]

Although there are hundreds of deceased Indigenous children yet to be found, investigations are increasing across the United States.[7]

Nationhood, Indian Wars, and western settlement[edit]

Through the 19th century, the encroachment of European Americans on Indian lands continued. From the 1830s, tribes from both the Southeast and the Great Lakes areas were pushed west of the Mississippi, forced off their lands to Indian Territory. As part of the treaties signed for land cessions, the United States was supposed to provide education to the tribes on their reservations. Some religious orders and organizations established missions in Kansas and what later became Oklahoma to work on these new reservations. Some of the Southeast tribes established their own schools, as the Choctaw did for both girls and boys.

After the Civil War and decades of Indian Wars in the West, more tribes were forced onto reservations after ceding vast amounts of land to the US. With the goal of assimilation, believed necessary so that tribal Indians could survive to become part of American society, the government increased its efforts to provide education opportunities. Some of this was related to the progressive movement, which believed the only way for the tribal peoples to make their way was to become assimilated, as American society was rapidly changing and urbanizing.

Following the Indian Wars, missionaries founded additional schools in the West with boarding facilities. Given the vast areas and isolated populations, they could support only a limited number of schools. Some children necessarily had to attend schools that were distant from their communities. Initially under President Ulysses S. Grant, only one religious organization or order was permitted on any single reservation. The various denominations lobbied the government to be permitted to set up missions, even in competition with each other.

Disease and death[edit]

Given the lack of public sanitation and the often crowded conditions at boarding schools in the early 20th century, students were at risk for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, and trachoma. None of these diseases was yet treatable by antibiotics or controlled by vaccines, and epidemics swept schools as they did cities.[35]

The overcrowding of the schools contributed to the rapid spread of disease within the schools. "An often-underpaid staff provided irregular medical care. And not least, apathetic boarding school officials frequently failed to heed their own directions calling for the segregation of children in poor health from the rest of the student body".[36] Tuberculosis was especially deadly among students. Many children died while in custody at Indian schools. Often students were prevented from communicating with their families, and parents were not notified when their children fell ill; the schools also failed sometimes to notify them when a child died. "Many of the Indian deaths during the great influenza pandemic of 1918–1919, which hit the Native American population hard, took place in boarding schools."[37]

The 1928 Meriam Report noted that infectious disease was often widespread at the schools due to malnutrition, overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and students weakened by overwork. The report said that death rates for Native American students were six and a half times higher than for other ethnic groups.[28] A report regarding the Phoenix Indian School said, "In December of 1899, measles broke out at the Phoenix Indian School, reaching epidemic proportions by January. In its wake, 325 cases of measles, 60 cases of pneumonia, and 9 deaths were recorded in a 10-day period."[38]

Schools in mid-20th century and later changes[edit]

Attendance in Indian boarding schools generally increased throughout the first half of the 20th century, doubling by the 1960s.[28]

In 1969, the BIA operated 226 schools in 17 states, including on reservations and in remote geographical areas. Some 77 were boarding schools. A total of 34,605 children were enrolled in the boarding schools; 15,450 in BIA day schools; and 3,854 were housed in dormitories "while attending public schools with BIA financial support. In addition, 62,676 Indian youngsters attend public schools supported by the Johnson-O'Malley Act, which is administered by BIA."[53]

Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children are estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding school.[28][54][55]

The rise of pan-Indian activism, tribal nations' continuing complaints about the schools, and studies in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (such as the Kennedy Report of 1969 and the National Study of American Indian Education) led to passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This emphasized authorizing tribes to contract with federal agencies in order to take over management of programs such as education. It also enabled the tribes to establish community schools for their children on their reservations.

In 1978, Congress passed and the President signed the Indian Child Welfare Act, giving Native American parents the legal right to refuse their child's placement in a school. Damning evidence related to years of abuses of students in off-reservation boarding schools contributed to the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Congress approved this act after hearing testimony about life in Indian boarding schools.

As a result of these changes, many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some located on reservations were taken over by tribes. By 2007, the number of American Indian children living in Indian boarding school dormitories had declined to 9,500.[6] This figure includes those in 45 on-reservation boarding schools, seven off-reservation boarding schools, and 14 peripheral dormitories.[6] From 1879 to the present day, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Native Americans attended Indian boarding schools as children.[56]

As of 2023, four federally run off-reservation boarding schools still exist.[57]

Native American tribes developed one of the first women's colleges.[58]

21st century[edit]

Circa 2020, the Bureau of Indian Education operates approximately 183[59] schools, primarily non-boarding, and primarily located on reservations. The schools have 46,000 students.[60] Modern criticisms focus on the quality of education provided and compliance with federal education standards.[60] In March 2020 the BIA finalized a rule to create the Standards, Assessments and Accountability System (SAAS) for all BIA schools. The motivation behind the rule is to prepare BIA students to be ready for college and careers.[61]