Ojibwe

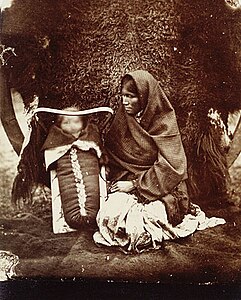

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains. They are Indigenous peoples of the Subarctic and Northeastern Woodlands.

For other uses, see Ojibwe (disambiguation).

According to the U.S. census, Ojibwe people are one of the largest tribal populations among Native American peoples in the United States. In Canada, they are the second-largest First Nations population, surpassed only by the Cree. They are one of the most numerous Indigenous Peoples north of the Rio Grande.[3] The Ojibwe population is approximately 320,000 people, with 170,742 living in the United States as of 2010,[1] and approximately 160,000 living in Canada.[2] In the United States there are 77,940 mainline Ojibwe, 76,760 Saulteaux, and 8,770 Mississauga, organized in 125 bands. In Canada they live from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia.

The Ojibwe language is Anishinaabemowin, a branch of the Algonquian language family.

They are part of the Council of Three Fires (which also include the Odawa and Potawatomi) and of the larger Anishinaabeg, which also include Algonquin, Nipissing, and Oji-Cree people. Historically, through the Saulteaux branch, they were a part of the Iron Confederacy with the Cree, Assiniboine, and Metis.[4]

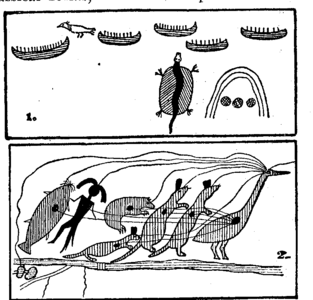

The Ojibwe are known for their birchbark canoes, birchbark scrolls, mining and trade in copper, as well as their harvesting of wild rice and maple syrup.[5] Their Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, oral history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.[6]

European powers, Canada, and the United States have colonized Ojibwe lands. The Ojibwe signed treaties with settler leaders to surrender land for settlement in exchange for compensation, land reserves and guarantees of traditional rights. Many European settlers moved into the Ojibwe ancestral lands.[7]

The exonym for this Anishinaabe group is Ojibwe (plural: Ojibweg). This word has two variations, one French (Ojibwa) and the other English (Chippewa).[8] Although many variations exist in the literature, Chippewa is more common in the United States, and Ojibway predominates in Canada,[9] but both terms are used in each country. In many Ojibwe communities throughout Canada and the U.S. since the late 20th century, more members have been using the generalized name Anishinaabe(-g).

The meaning of the name Ojibwe is not known; the most common explanations for the name's origin are:

Because many Ojibwe were formerly located around the outlet of Lake Superior, which the French colonists called Sault Ste. Marie for its rapids, the early Canadian settlers referred to the Ojibwe as Saulteurs. Ojibwe who subsequently moved to the prairie provinces of Canada have retained the name Saulteaux. This is disputed since some scholars believe that only the name migrated west.[14] Ojibwe who were originally located along the Mississagi River and made their way to southern Ontario are known as the Mississaugas.[15]

History[edit]

Precontact and spiritual beliefs[edit]

According to Ojibwe oral history and from recordings in birch bark scrolls, the Ojibwe originated from the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River on the Atlantic coast of what is now Quebec.[17] They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years as they migrated, and knew of the canoe routes to move north, west to east, and then south in the Americas. The identification of the Ojibwe as a culture or people may have occurred in response to contact with Europeans. The Europeans preferred to deal with groups, and tried to identify those they encountered.[18]

According to Ojibwe oral history, seven great miigis (Cowrie shells) appeared to them in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e., Eastern Land) to teach them the mide way of life. One of the miigis was too spiritually powerful and killed the people in the Waabanakiing when they were in its presence. The six others remained to teach, while the one returned into the ocean. The six established doodem (clans) for people in the east, symbolized by animals. The five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose). The six miigis then returned to the ocean as well. If the seventh had stayed, it would have established the Thunderbird doodem.

At a later time, one of these miigis appeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. It said that if the Anishinaabeg did not move farther west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new pale-skinned settlers who would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed with miigis shells (i.e., cowry shells). After receiving assurance from their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e., Abenaki) of their safety to move inland, the Anishinaabeg gradually migrated west along the Saint Lawrence River to the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing, and then to the Great Lakes.

The first of the smaller Turtle Islands was Mooniyaa, where Mooniyaang (present-day Montreal)[19] developed. The "second stopping place" was in the vicinity of the Wayaanag-gakaabikaa (Concave Waterfalls, i.e., Niagara Falls). At their "third stopping place", near the present-day city of Detroit, Michigan, the Anishinaabeg divided into six groups, of which the Ojibwe was one.

The first significant new Ojibwe culture-center was their "fourth stopping place" on Manidoo Minising (Manitoulin Island). Their first new political-center was referred to as their "fifth stopping place", in their present country at Baawiting (Sault Ste. Marie).

Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwe divided into the "northern branch", following the north shore of Lake Superior, and the "southern branch", along its south shore.

As the people continued to migrate westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group". The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island (46°41′15″N 092°11′21″W / 46.68750°N 92.18917°W) located in the Saint Louis River estuary at the western end of Lake Superior. (This has since been developed as the present-day Duluth/Superior cities.) The people were directed in a vision by the miigis being to go to the "place where there is food (i.e., wild rice) upon the waters." Their second major settlement, referred to as their "seventh stopping place", was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, French, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present La Pointe, Wisconsin.

The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" migrated along the Rainy River, Red River of the North, and across the northern Great Plains until reaching the Pacific Northwest. Along their migration to the west, they came across many miigis, or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy.

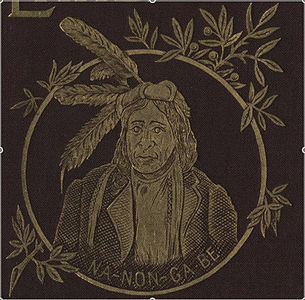

![A-na-cam-e-gish-ca (Aanakamigishkaang/"[Traces of] Foot Prints [upon the Ground]"), Ojibwe chief, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/A-na-cam-e-gish-ca.jpg/180px-A-na-cam-e-gish-ca.jpg)