Nehru Report

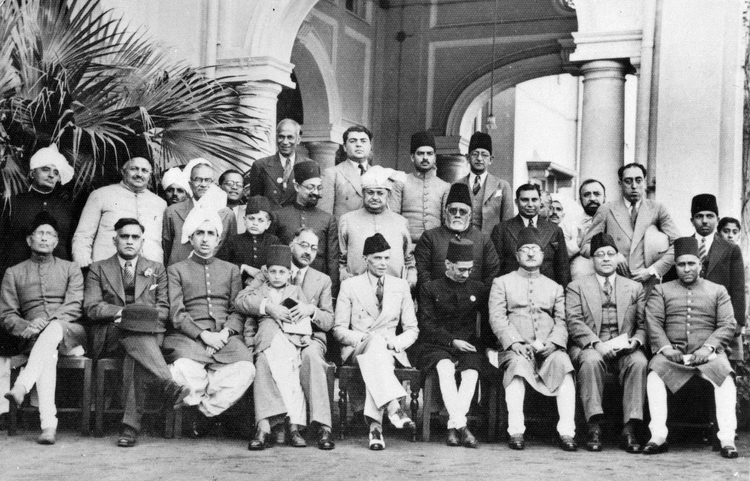

The Nehru Report of 1928 was a memorandum by All Parties Conference in British India to appeal for a new dominion status and a federal set-up of government for the constitution of India. It also proposed for the Joint Electorates with reservation of seats for minorities in the legislatures. It was prepared by a committee chaired by Motilal Nehru, with Jawaharlal Nehru acting as the secretary. There were nine other members in the committee. The final report was signed by Motilal Nehru and Jawaharlal Nehru, Ali Imam, Tej Bahadur Sapru, Madhav Shrihari Aney, Mangal Singh, Shuaib Qureshi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and G. R. Pradhan.[1]

M K Gandhi proposed a resolution saying that British should be given one year to accept the recommendations of the Nehru report or a campaign of non-cooperation would begin. The resolution was passed.

The constitution outlined by the Nehru Report was for Indian enjoying dominion status within the British Commonwealth. Some of the important elements of the report:

Element of Nehru report...

The Nehru Report, along with that of the Simon Commission was available to participants in the three Indian Round Table Conferences (1930–1932). However, the Government of India Act 1935 owes much to the Simon Commission report and little, if anything to the Nehru Report.

With few exceptions League leaders failed to pass the Nehru proposals. In reaction Mohammad Ali Jinnah drafted his Fourteen Points in 1929 which became the core demands of the Muslim community which they put forward as the price of their participating in an independent united India. Their main objections were:

According to Mohammad Ali Jinnah, “The Committee has adopted a narrow minded policy to ruin the political future of the Muslims.

I regret to declare that the report is extremely ambiguous and does not deserve to be implemented.”

Reception[edit]

R.Coupland in The Constitutional Problem in India[4] saw the Report as the "frankest attempt yet made by Indians to face squarely the difficulties of communalism..." and found its objective of claiming dominion status as remarkable. However, he argued that the Report "had little practical result". Granville Austin in India’s Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation, highlighted that the fundamental rights section of the Nehru Report was "a close precursor of the Fundamental Rights of the Constitution [of India, 1950]…10 of the 19 subclauses re-appear, materially unchanged, and three of the Nehru rights are included in the Directive Principles". Neera Chandhoke’s in her chapter in The Indian Constituent Assembly (edited) argued that "the inclusion of social and cultural rights in a predominantly liberal constitution appears extraordinary". Niraja Jayal in Citizenship and Its Discontents suggested that the Nehru Report, in the context of the international discourse of rights around the late 1920s, was a "rather exceptional document in its early envisioning of social and economic rights".[2]