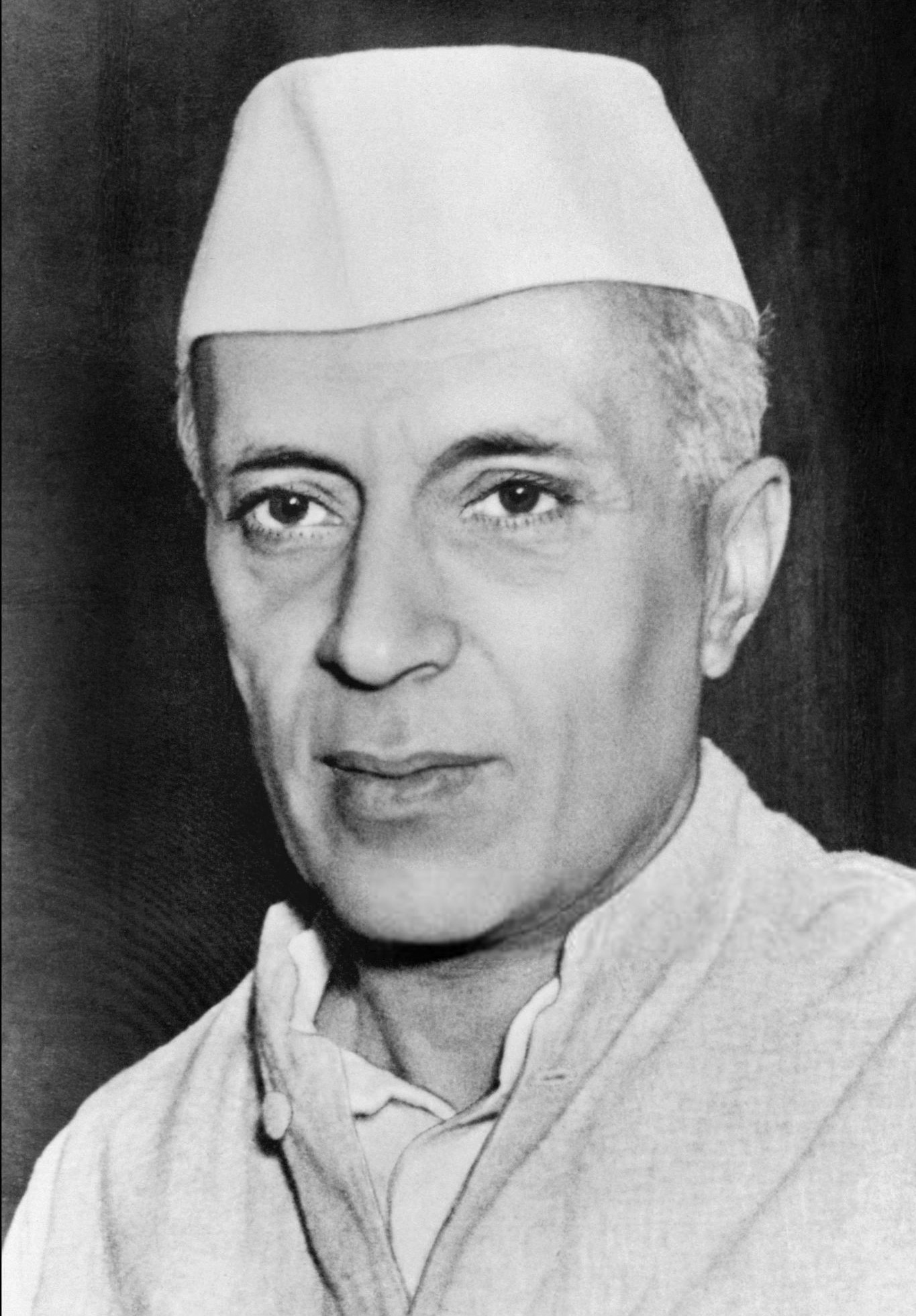

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (/ˈneɪru/ NAY-roo or /ˈnɛru/ NEH-roo;[1] Hindi: [ˈdʒəʋɑːɦəɾˈlɑːl ˈneːɦɾuː] ⓘ; juh-WAH-hurr-LAHL NE-hǝ-ROO; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, statesman, secular humanist, social democrat,[2] and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a principal leader of the Indian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s. Upon India's independence in 1947, he served as the country's first prime minister for 16 years.[3] Nehru promoted parliamentary democracy, secularism, and science and technology during the 1950s, powerfully influencing India's arc as a modern nation. In international affairs, he steered India clear of the two blocs of the Cold War. A well-regarded author, his books written in prison, such as Letters from a Father to His Daughter (1929), An Autobiography (1936) and The Discovery of India (1946), have been read around the world.

"Nehru" redirects here. For other uses, see Nehru (disambiguation).

Jawaharlal Nehru

George VI (until 1950)

- Rajendra Prasad (from 1950)

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

- Lord Mountbatten

- C. Rajagopalachari (until 1950)

Vallabhbhai Patel (until 1950)

Post established

- Earl Wavell

- Lord Mountbatten

Constituency established

Phulpur, Uttar Pradesh

14 November 1889

Allahabad, North-Western Provinces, British India

27 May 1964 (aged 74)

New Delhi, India

See awards section

The son of Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and Indian nationalist, Jawaharlal Nehru was educated in England—at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge, and trained in the law at the Inner Temple. He became a barrister, returned to India, enrolled at the Allahabad High Court and gradually began to take an interest in national politics, which eventually became a full-time occupation. He joined the Indian National Congress, rose to become the leader of a progressive faction during the 1920s, and eventually of the Congress, receiving the support of Mahatma Gandhi who was to designate Nehru as his political heir. As Congress president in 1929, Nehru called for complete independence from the British Raj.

Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s. Nehru promoted the idea of the secular nation-state in the 1937 provincial elections, allowing the Congress to sweep the elections, and to form governments in several provinces. In September 1939, the Congress ministries resigned to protest Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to join the war without consulting them. After the All India Congress Committee's Quit India Resolution of 8 August 1942, senior Congress leaders were imprisoned and for a time the organisation was suppressed. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi's call for immediate independence, and had desired instead to support the Allied war effort during World War II, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much altered political landscape. The Muslim League, under Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had come to dominate Muslim politics in the interim. In the 1946 provincial elections, Congress won the elections but the League won all the seats reserved for Muslims, which the British interpreted to be a clear mandate for Pakistan in some form. Nehru became the interim prime minister of India in September 1946, with the League joining his government with some hesitancy in October 1946.

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, Nehru gave a critically acclaimed speech, "Tryst with Destiny"; he was sworn in as the Dominion of India's prime minister and raised the Indian flag at the Red Fort in Delhi. On 26 January 1950, when India became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations, Nehru became the Republic of India's first prime minister. He embarked on an ambitious program of economic, social, and political reforms. Nehru promoted a pluralistic multi-party democracy. In foreign affairs, he played a leading role in establishing Non-Aligned Movement, a group of nations that did not seek membership in the two main ideological blocs of the Cold War.

Under Nehru's leadership, the Congress emerged as a catch-all party, dominating national and state-level politics and winning elections in 1951, 1957 and 1962. His premiership, spanning 16 years and 286 days—which is, to date, the longest in India—ended with his death in 1964 from a heart attack. Hailed as the "architect of Modern India", his birthday is celebrated as Children's Day in India.[4]

Nationalist movement (1912–1938)

Britain and return to India: 1912–1913

Nehru had developed an interest in Indian politics during his time in Britain as a student and a barrister.[23] Within months of his return to India in 1912, Nehru attended an annual session of the Indian National Congress in Patna.[24] Congress in 1912 was the party of moderates and elites,[24] and he was disconcerted by what he saw as "very much an English-knowing upper-class affair".[25] Nehru doubted the effectiveness of Congress but agreed to work for the party in support of the Indian civil rights movement led by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa,[26] collecting funds for the movement in 1913.[24] Later, he campaigned against indentured labour and other such discrimination faced by Indians in the British colonies.[27]

World War I: 1914–1915

When World War I broke out, sympathy in India was divided. Although educated Indians "by and large took a vicarious pleasure" in seeing the British rulers humbled, the ruling upper classes sided with the Allies. Nehru confessed he viewed the war with mixed feelings. As Frank Moraes writes, "if [Nehru's] sympathy was with any country it was with France, whose culture he greatly admired".[28] During the war, Nehru volunteered for the St. John Ambulance and worked as one of the organisation's provincial secretaries Allahabad.[24] He also spoke out against the censorship acts passed by the British government in India.[29]

Nehru emerged from the war years as a leader whose political views were considered radical. Although the political discourse at the time had been dominated by the moderate, Gopal Krishna Gokhale,[26] who said that it was "madness to think of independence,"[24] Nehru had spoken, "openly of the politics of non-cooperation, of the need of resigning from honorary positions under the government and of not continuing the futile politics of representation".[30] He ridiculed the Indian Civil Service for supporting British policies. He noted someone had once defined the Indian Civil Service, "with which we are unfortunately still afflicted in this country, as neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service".[31] Motilal Nehru, a prominent moderate leader, acknowledged the limits of constitutional agitation but counselled his son that there was no other "practical alternative" to it. Nehru, however, was dissatisfied with the pace of the national movement. He became involved with aggressive nationalists leaders demanding Home Rule for Indians.[32]

The influence of moderates on Congress' politics waned after Gokhale died in 1915.[24] Anti-moderate leaders like Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak took the opportunity to call for a national movement for Home Rule. However, in 1915, the proposal was rejected because of the reluctance of the moderates to commit to such a radical course of action.[33]

Key cabinet members and associates

Nehru served as the prime minister for eighteen years, first as interim prime minister during 1946–1947 during the last year of the British Raj and then as prime minister of independent India from 15 August 1947 to 27 May 1964.

V. K. Krishna Menon (1896–1974) was a close associate of Nehru, and was described as the second most powerful man in India during Nehru's tenure as prime minister. From the inception of Nehru's prime ministry, Menon carefully selected Lord Mountbatten as the only suitable candidate and presented him as such to Labour through Sir Stafford Cripps and Clement Attlee, who promptly appointed him the last Viceroy. the early governance and partition ultimately reduced to Mountbatten, Nehru, Menon, V.P. Menon, Sardar Patel, and an adamant Jinnah. Under Nehru, he served as India's high commissioner to the UK, ambassador to Ireland, ambassador-at-large and plenipotentiary, UN ambassador, minister without portfolio, de facto Foreign minister, and Union minister of defence. He was significantly involved in the annexation of Goa. He resigned after the debacle of the 1962 China War but remain a close friend of Nehru.[259][260][261][262]

B. R. Ambedkar, the law minister in the interim cabinet, also chaired the Constitution Drafting Committee.[263]

Vallabhbhai Patel served as home minister in the interim government. He was instrumental in getting the Congress party working committee to vote for partition. He is also credited with integrating many princely states of India. Patel was a long-time comrade to Nehru but died in 1950, leaving Nehru as the unchallenged leader of India until his own death in 1964.[264]

Maulana Azad was the First Minister of Education in the Indian government Minister of Human Resource Development (until 25 September 1958, Ministry of Education). His contribution to establishing the education foundation in India is recognised by celebrating his birthday as National Education Day across India.[265][266]

Jagjivan Ram became the youngest minister in Nehru's Interim Government of India, a labour minister and also a member of the Constituent Assembly of India, where, as a member of the Dalit caste, he ensured that social justice was enshrined in the Constitution. He went on to serve as a minister with various portfolios during Nehru's tenure and in Shastri and Indira Gandhi governments.[267]

Morarji Desai was a nationalist with anti-corruption leanings but was socially conservative, pro-business, and in favour of free enterprise reforms, as opposed to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's socialistic policies. After serving as chief minister of Bombay State, he joined Nehru's cabinet in 1956 as the finance minister of India. he held that position until 1963 when he along with other senior ministers in the Nehru cabinet resigned under the Kamaraj plan.The plan, as proposed by Madras Chief Minister K.Kamaraj, was to revert government ministers to party positions after a certain tenure and vice versa. With Nehru's age and health failing in the early 1960s, Desai was considered a possible contender for the position of Prime Minister.[268][269] Later Desai alleged that Nehru used the Kamaraj Plan to remove all possible contenders 'from the path of his daughter, Indira Gandhi.[270] Desai succeeded Indira Gandhi as the prime minister in 1977 when he was selected by the victorious Janata alliance as their parliamentary leader.[271]

Govind Ballabh Pant (1887–1961) was a key figure in the Indian independence movement and later a pivotal figure in the politics of Uttar Pradesh (UP) and in the Indian Government. Pant served in Nehru's cabinet as Union home minister from 1955 until his death in 1961.[272] As home minister, his chief achievement was the re-organisation of states along linguistic lines. He was also responsible for the establishment of Hindi as the official language of the central government and a few states.[273] During his tenure as the home minister, Pant was awarded the Bharat Ratna.[274]

C. D. Deshmukh was one of five members of the Planning Commission when it was constituted in 1950 by a cabinet resolution.[275][276] Deshmukh succeeded John Mathai as the Union Finance Minister in 1950 after Mathai resigned in protest over the transfer of certain powers to the Planning Commission.[277] As finance minister, Deshmukh remained a member of the Planning Commission.[278] Deshmukh's tenure—during which he delivered six budgets and an interim budget[279]—is noted for the effective management of the Indian economy and its steady growth which saw it recover from the impacts of the events of the 1940s.[280][281] During Deshmukh's tenure, the State Bank of India was formed in 1955 through the nationalisation and amalgamation of the Imperial Bank with several smaller banks.[282][283] He accomplished the nationalisation of insurance companies and the formation of the Life Insurance Corporation of India through the Life Insurance Corporation of India Act, 1956.[284][285] Deshmukh resigned over the Government's proposal to move a bill in Parliament bifurcating Bombay State into Gujarat and Maharashtra while designating the city of Bombay a Union territory.[286][287]

In the years following independence, Nehru frequently turned to his daughter Indira Gandhi for managing his personal affairs.[288] Indira moved into Nehru's official residence to attend to him and became his constant companion in his travels across India and the world. She would virtually become Nehru's chief of staff.[289] Towards the end of the 1950s, Indira Gandhi served as the president of the Congress. In that capacity, she was instrumental in getting the Communist-led Kerala State Government dismissed in 1959.[290] Indira was elected as Congress party president in 1959, which aroused criticism for alleged nepotism, although Nehru had actually disapproved of her election, partly because he considered that it smacked of "dynasticism"; he said, indeed it was "wholly undemocratic and an undesirable thing", and refused her a position in his cabinet.[291] Indira herself was at loggerheads with her father over policy; most notably, she used his oft-stated personal deference to the Congress Working Committee to push through the dismissal of the Communist Party of India government in the state of Kerala, over his own objections.[291] Nehru began to be embarrassed by her ruthlessness and disregard for parliamentary tradition and was "hurt" by what he saw as an assertiveness with no purpose other than to stake out an identity independent of her father.[292]