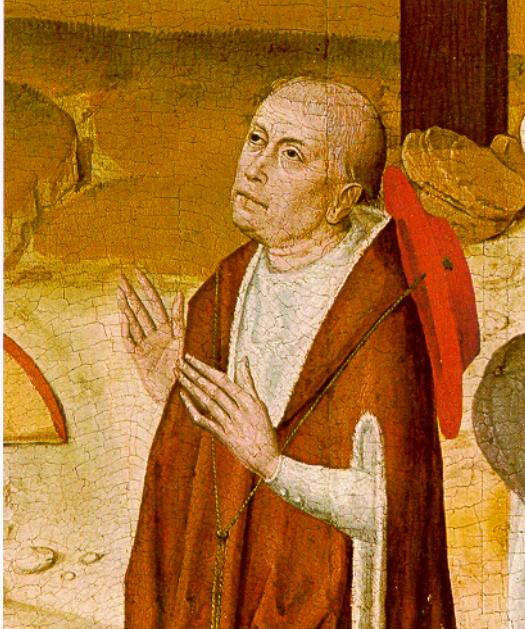

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (/kjuːˈseɪnəs/), was a German Catholic cardinal and polymath active as a philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renaissance humanism, he made spiritual and political contributions in European history. A notable example of this is his mystical or spiritual writings on "learned ignorance," as well as his participation in power struggles between Rome and the German states of the Holy Roman Empire.

"Cusa" and "Cusanus" redirect here. For the lunar crater, see Cusanus (crater). For other uses, see CUSA (disambiguation).

Nicholas of Cusa

11 August 1464

Doctor Christianus, "Nikolaus Cryfftz", "Nicholas of Kues", "Nicolaus Cusanus"

1450–1464

1436[2]

26 April 1450[2]

by Pope Nicholas V

20 December 1448

by Pope Nicholas V

As papal legate to Germany from 1446, he was appointed cardinal for his merits by Pope Nicholas V in 1448 and Prince–Bishop of Brixen two years later. In 1459, he became vicar general in the Papal States.

Nicholas has remained an influential figure. In 2001, the sixth centennial of his birth was celebrated on four continents and commemorated by publications on his life and work.[4]

Philosophy[edit]

Nicholas's De Docta Ignorantia ('Of Learned Ignorance') is an epistemological and metaphysical treatise. He maintains the finite human mind cannot fully know the divine, infinite mind ('the Maximum'). Nonetheless, he holds that the human intellect can become aware of its limitations in knowing God and thus attain "learned ignorance". His theory shows the influence of neoplatonism and negative theology, and he frequently cites Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.

Nicholas was noted for his deeply mystical writings about Christianity. He wrote of the enfolding of creation in God and their unfolding in creation. He was suspected by some of holding pantheistic beliefs, but his writings were never accused of being heretical.[10] Nicholas also wrote in De coniecturis about using conjectures or surmises to rise to better understanding of the truth. The individual might rise above mere reason to the vision of the intellect, but the same person might fall back from such vision.

Theologically, Nicholas anticipated the implications of Reformed teaching on the harrowing of Hell (Sermon on Psalm 30:11), followed by Pico della Mirandola, who similarly explained the descensus in terms of Christ's agony.

Other religions[edit]

Shortly after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, Nicholas wrote De pace fidei, On the Peace of Faith. This visionary work imagined a summit meeting in Heaven of representatives of all nations and religions. Islam and the Hussite movement in Bohemia are represented. The conference agrees that there can be una religio in varietate rituum, a single faith manifested in different rites, as manifested in the eastern and western rites of the Catholic Church. The dialog presupposes the greater accuracy of Christianity but gives respect to other religions.[21] Nicholas's position was for Europeans not to retake Constantinople but simply to trade with the Ottomans and allow them their conquests. Less irenic but not virulent, is his Cribratio Alchorani, Sifting the Koran, a detailed review of the Koran in Latin translation. While the arguments for the superiority of Christianity are still shown in this book, it also credits Judaism and Islam with sharing in the truth at least partially.[22]

Influence[edit]

Nicholas was widely read, and his works were published in the sixteenth century in both Paris and Basel. Sixteenth-century French scholars, including Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples and Charles de Bovelles, cited him. Lefèvre even edited the Paris 1514 Opera.[23] Nonetheless, there was no Cusan school, and his works were largely unknown until the nineteenth century, though Giordano Bruno quoted him, while some thinkers, like Gottfried Leibniz, were thought to have been influenced by him.[24] Neo-Kantian scholars began studying Nicholas in the nineteenth century, and new editions were begun by the Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften in the 1930s and published by Felix Meiner Verlag.[25] In the early twentieth century, he was hailed by Ernst Cassirer as the "first modern thinker,"[26] and much debate since then has centered around the question whether he should be seen as essentially a medieval or Renaissance figure. What is more, Cassirer presented Cusanus as the main focal point (einfachen Brennpunkt) of Italian Renaissance philosophy. Eminent scholars like Eugenio Garin and Paul Oskar Kristeller challenged Cassirer’s thesis, and went so far as to practically deny any considerable link between Nicholas of Cusa and Marsilio Ficino or Giovanni Pico.[27] In the following decades, new hypotheses on the relationship between Cusanus and Italian humanists appeared, more balanced and focused on the sources.[28]

Societies and centers dedicated to Nicholas can be found in Argentina, Japan, Germany, Italy and the United States. His well-known quote about the infinity of the universe is found paraphrased in the Central Holy Book of the Thelemites, The Book of the Law, which was "received" from the Angel Aiwass by Aleister Crowley in Cairo in April 1904: "In the sphere I am everywhere the centre, as she, the circumference, is nowhere found."

In popular culture[edit]

In the paradox interactive grand strategy game Europa Universalis IV, Nicholas is a hireable advisor for Austria in the 1444 start date as (natural scientist) Nikolaus von Kues.