Medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries.[1] Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century,[1] and in France and Germany, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne in Aachen, in the last quarter of the 8th century.[1][2] It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period,[1] and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning. This is one of the defining characteristics in this time period. Understanding God was the focal point of study of the philosophers at that time, Muslim and Christian alike.

The history of medieval philosophy is traditionally divided into two main periods: the period in the Latin West following the Early Middle Ages until the 12th century, when the works of Aristotle and Plato were rediscovered, translated, and studied upon, and the "golden age" of the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries in the Latin West, which witnessed the culmination of the recovery of ancient philosophy, along with the reception of its Arabic commentators,[1] and significant developments in the fields of philosophy of religion, logic, and metaphysics.

The high medieval Scholastic period was disparagingly treated by the Renaissance humanists, who saw it as a barbaric "middle period" between the Classical age of Greek and Roman culture, and the rebirth or renaissance of Classical culture.[1] Modern historians consider the medieval era to be one of philosophical development, heavily influenced by Christian theology. One of the most notable thinkers of the era, Thomas of Aquinas, never considered himself a philosopher, and criticized philosophers for always "falling short of the true and proper wisdom".[3]

The problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and simplicity of God, the purpose of theology and metaphysics, and the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.[4]: 1

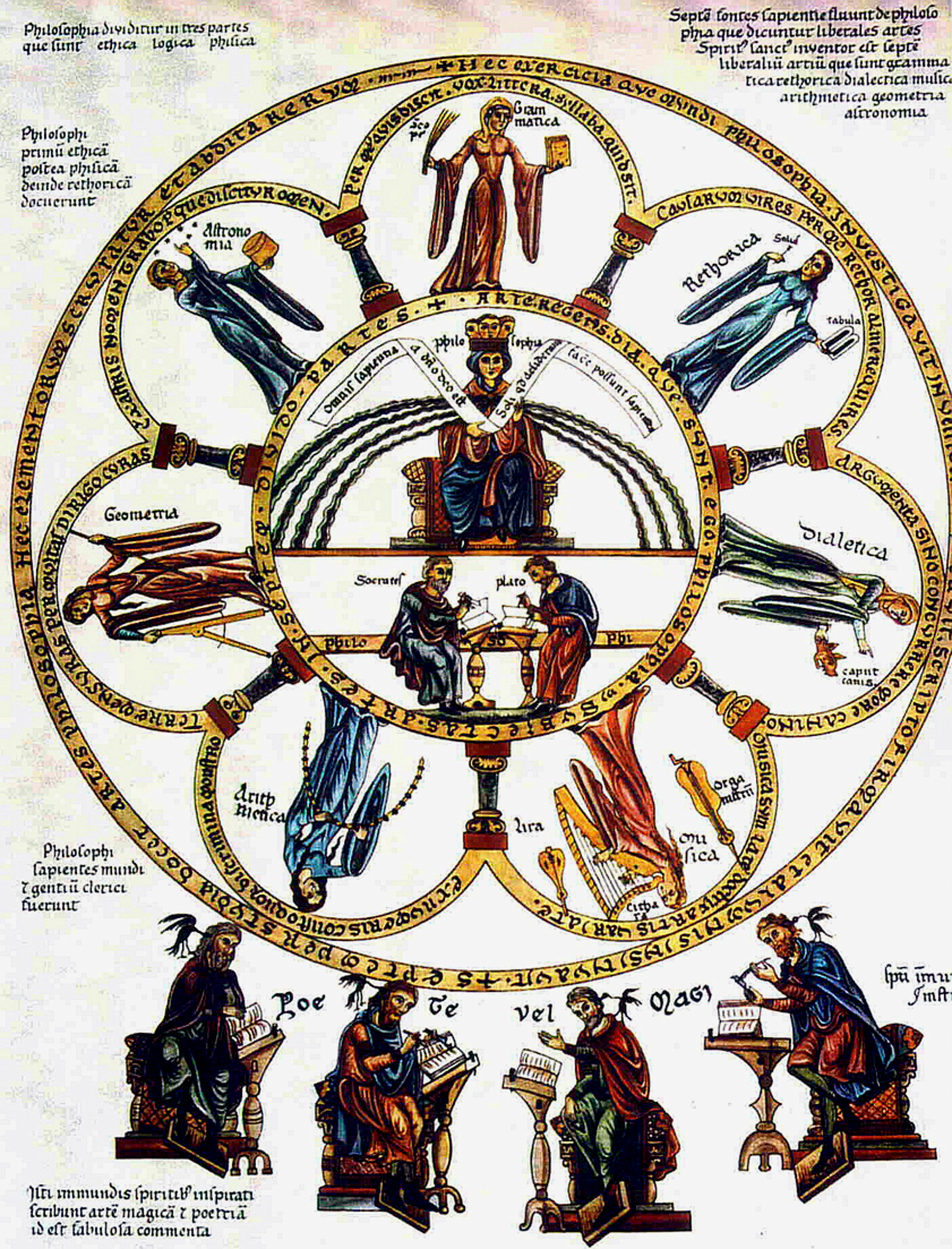

Medieval philosophy places heavy emphasis on the theological.[5] With the possible exceptions of Avicenna and Averroes, medieval thinkers did not consider themselves philosophers at all: for them, the philosophers were the ancient pagan writers such as Plato and Aristotle.[4]: 1 However, their theology used the methods and logical techniques of the ancient philosophers to address difficult theological questions and points of doctrine. Thomas Aquinas, following Peter Damian, argued that philosophy is the handmaiden of theology (philosophia ancilla theologiae).[4]: 35 Despite this view of philosophy as the servant of theology, this did not prevent the medievals from developing original and innovative philosophies against the backdrop of their theological projects. For instance, such thinkers as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas of Aquinas made monumental breakthroughs in the philosophy of temporality and metaphysics, respectively.

The principles that underlie all the medieval philosophers' work are:

One of the most heavily debated things of the period was that of faith versus reason. Avicenna and Averroes both leaned more on the side of reason. Augustine stated that he would never allow his philosophical investigations to go beyond the authority of God.[6]: 27 Anselm attempted to defend against what he saw as partly an assault on faith, with an approach allowing for both faith and reason. The Augustinian solution to the faith/reason problem is to first believe, and then subsequently seek to understand (fides quaerens intellectum). This was the mantra of Christian thinkers, most especially the scholastic philosophers (Albert the Great, Bonaventure, and Thomas Aquinas).