Ontological argument

An ontological argument is a deductive philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments are commonly conceived a priori in regard to the organization of the universe, whereby, if such organizational structure is true, God must exist.

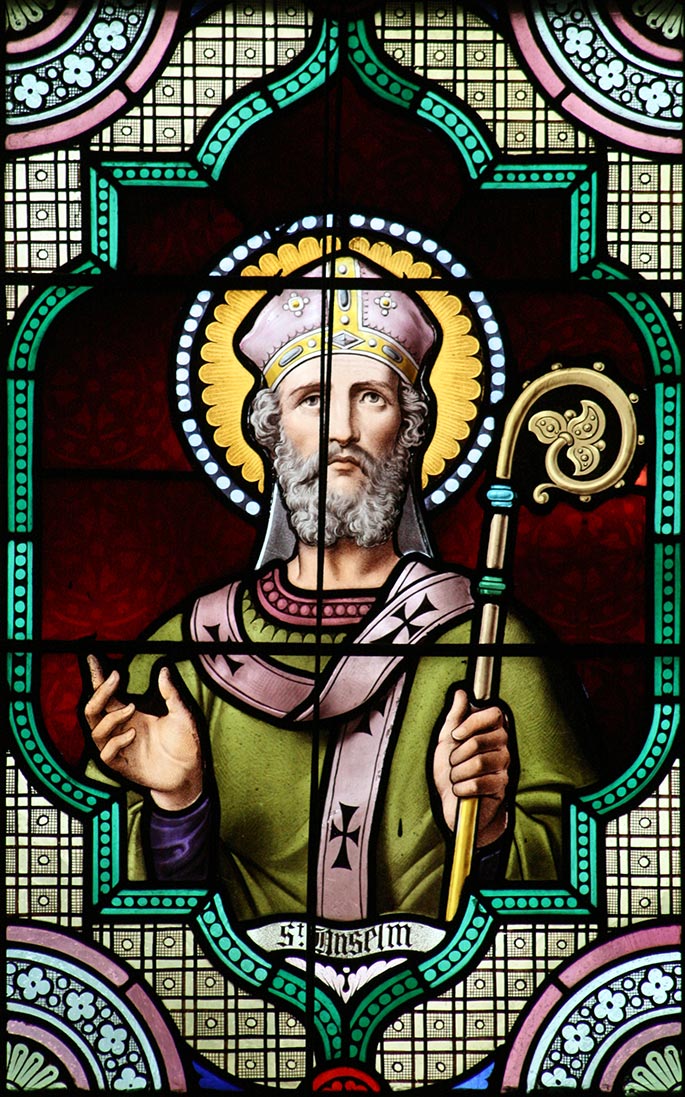

The first ontological argument in Western Christian tradition[i] was proposed by Saint Anselm of Canterbury in his 1078 work, Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, lit. 'Discourse [on the Existence of God]'), in which he defines God as "a being than which no greater can be conceived," and argues that such a being must exist in the mind, even in that of the person who denies the existence of God.[1] From this, he suggests that if the greatest possible being exists in the mind, it must also exist in reality, because if it existed only in the mind, then an even greater being must be possible—one who exists both in mind and in reality. Therefore, this greatest possible being must exist in reality. Similarly, in the East, Avicenna's Proof of the Truthful argued, albeit for very different reasons, that there must be a "necessary existent".[2]

Seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes employed a similar argument to Anselm's. Descartes published several variations of his argument, each of which center on the idea that God's existence is immediately inferable from a "clear and distinct" idea of a supremely perfect being. In the early 18th century, Gottfried Leibniz augmented Descartes' ideas in an attempt to prove that a "supremely perfect" being is a coherent concept. A more recent ontological argument came from Kurt Gödel, who proposed a formal argument for God's existence. Norman Malcolm also revived the ontological argument in 1960 when he located a second, stronger ontological argument in Anselm's work; Alvin Plantinga challenged this argument and proposed an alternative, based on modal logic. Attempts have also been made to validate Anselm's proof using an automated theorem prover. Other arguments have been categorised as ontological, including those made by Islamic philosophers Mulla Sadra and Allama Tabatabai.

Just as the ontological argument has been popular, a number of criticisms and objections have also been mounted. Its first critic was Gaunilo of Marmoutiers, a contemporary of Anselm's. Gaunilo, suggesting that the ontological argument could be used to prove the existence of anything, uses the analogy of a perfect island. Such would be the first of many parodies, all of which attempted to show the absurd consequences of the ontological argument. Later, Thomas Aquinas rejected the argument on the basis that humans cannot know God's nature. David Hume also offered an empirical objection, criticising its lack of evidential reasoning and rejecting the idea that anything can exist necessarily. Immanuel Kant's critique was based on what he saw as the false premise that existence is a predicate, arguing that "existing" adds nothing (including perfection) to the essence of a being. Thus, a "supremely perfect" being can be conceived not to exist. Finally, philosophers such as C. D. Broad dismissed the coherence of a maximally great being, proposing that some attributes of greatness are incompatible with others, rendering "maximally great being" incoherent.

Contemporary defenders of the ontological argument include Alvin Plantinga, Yujin Nagasawa, and Robert Maydole.

The traditional definition of an ontological argument was given by Immanuel Kant.[3] He contrasted the ontological argument (literally any argument "concerned with being")[4] with the cosmological and physio-theoretical arguments.[5] According to the Kantian view, ontological arguments are those founded through a priori reasoning.[3]

Graham Oppy, who elsewhere expressed that he "see[s] no urgent reason" to depart from the traditional definition,[3] defined ontological arguments as those which begin with "nothing but analytic, a priori and necessary premises" and conclude that God exists. Oppy admits, however, that not all of the "traditional characteristics" of an ontological argument (i.e. analyticity, necessity, and a priority) are found in all ontological arguments[1] and, in his 2007 work Ontological Arguments and Belief in God, suggested that a better definition of an ontological argument would employ only considerations "entirely internal to the theistic worldview."[3]

Oppy subclassified ontological arguments, based on the qualities of their premises, using the following qualities:[1][3]

William Lane Craig criticised Oppy's study as too vague for useful classification. Craig argues that an argument can be classified as ontological if it attempts to deduce the existence of God, along with other necessary truths, from his definition. He suggests that proponents of ontological arguments would claim that, if one fully understood the concept of God, one must accept his existence.[7]

William L. Rowe defines ontological arguments as those which start from the definition of God and, using only a priori principles, conclude with God's existence.[8]

Criticisms and objections[edit]

Gaunilo[edit]

One of the earliest recorded objections to Anselm's argument was raised by one of Anselm's contemporaries, Gaunilo of Marmoutiers. He invited his reader to conceive an island "more excellent" than any other island. He suggested that, according to Anselm's proof, this island must necessarily exist, as an island that exists would be more excellent.[52] Gaunilo's criticism does not explicitly demonstrate a flaw in Anselm's argument; rather, it argues that if Anselm's argument is sound, so are many other arguments of the same logical form, which cannot be accepted.[53] He offered a further criticism of Anselm's ontological argument, suggesting that the notion of God cannot be conceived, as Anselm had asserted. He argued that many theists would accept that God, by nature, cannot be fully comprehended. Therefore, if humans cannot fully conceive of God, the ontological argument cannot work.[54]

Anselm responded to Gaunilo's criticism by arguing that the argument applied only to concepts with necessary existence. He suggested that only a being with necessary existence can fulfill the remit of "that than which nothing greater can be conceived". Furthermore, a contingent object, such as an island, could always be improved and thus could never reach a state of perfection. For that reason, Anselm dismissed any argument that did not relate to a being with necessary existence.[52]

Other parodies have been presented, including the devil corollary, the no devil corollary and the extreme no devil corollary. The devil corollary proposes that a being than which nothing worse can be conceived exists in the understanding (sometimes the term lesser is used in place of worse). Using Anselm's logical form, the parody argues that if it exists in the understanding, a worse being would be one that exists in reality; thus, such a being exists. The no devil corollary is similar, but argues that a worse being would be one that does not exist in reality, so does not exist. The extreme no devil corollary advances on this, proposing that a worse being would be that which does not exist in the understanding, so such a being exists neither in reality nor in the understanding. Timothy Chambers argued that the devil corollary is more powerful than Gaunilo's challenge because it withstands the challenges that may defeat Gaunilo's parody. He also claimed that the extreme no devil corollary is a strong challenge, as it "underwrites" the no devil corollary, which "threatens Anselm's argument at its very foundations".[55] Christopher New and Stephen Law argue that the ontological argument is reversible, and if it is sound, it can also be used to prove the existence of a maximally evil god in the Evil God challenge.[56]

Thomas Aquinas[edit]

Thomas Aquinas, while proposing five proofs of God's existence in his Summa Theologica, objected to Anselm's argument. He suggested that people cannot know the nature of God and, therefore, cannot conceive of God in the way Anselm proposed.[57] The ontological argument would be meaningful only to someone who understands the essence of God completely. Aquinas reasoned that, as only God can completely know His essence, only He could use the argument.[58] His rejection of the ontological argument led other Catholic theologians to also reject the argument.[59]