Panama Canal

The Panama Canal (Spanish: Canal de Panamá) is an artificial 82-kilometre (51-mile) waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean, cutting across the Isthmus of Panama, and is a conduit for maritime trade. Locks at each end lift ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial fresh water lake 26 meters (85 ft) above sea level, created by damming up the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal. Locks then lower the ships at the other end. An average of 200,000,000 L (52,000,000 US gal) of fresh water is used in a single passing of a ship. The canal is threatened by low water levels during droughts.

Panama Canal

Canal de Panamá

82 km (51 miles)

366 m (1,200 ft 9 in)

49 m (160 ft 9 in)

(originally 28.5 m or 93 ft 6 in)

15.2 m (50 ft)

57.91 m (190.0 ft)

3 locks up, 3 down per transit; all three lanes

(3 lanes of locks)

Opened in 1914; expansion opened June 26, 2016

Ferdinand de Lesseps, John Findley Wallace (1904–1905), John Frank Stevens (1905–1907), George Washington Goethals (1907–1914)

May 4, 1904

August 15, 1914

June 26, 2016

Atlantic Ocean

Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean from Atlantic Ocean and vice versa

The Panama Canal shortcut greatly reduces the time for ships to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, enabling them to avoid the lengthy, hazardous route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage or Strait of Magellan. It is one of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken.

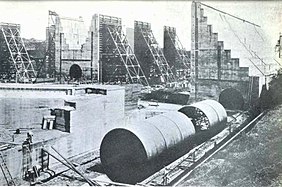

Colombia, France, and later the United States controlled the territory surrounding the canal during construction. France began work on the canal in 1881, but stopped because of lack of investors' confidence due to engineering problems and a high worker mortality rate. The US took over the project in 1904 and opened the canal in 1914. The US continued to control the canal and surrounding Panama Canal Zone until the Torrijos–Carter Treaties provided for its handover to Panama in 1977. After a period of joint American–Panamanian control, the Panamanian government took control in 1999. It is now managed and operated by the Panamanian government-owned Panama Canal Authority.

The original locks are 33.5 meters (110 ft) wide and allow the passage of Panamax ships. A third, wider lane of locks was constructed between September 2007 and May 2016. The expanded waterway began commercial operation on June 26, 2016. The new locks allow transit of larger, Neopanamax ships.

Annual traffic has risen from about 1,000 ships in 1914, when the canal opened, to 14,702 vessels in 2008, for a total of 333.7 million Panama Canal/Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) tons. By 2012, more than 815,000 vessels had passed through the canal.[1] In 2017, it took ships an average of 11.38 hours to pass between the canal's two outer locks. The American Society of Civil Engineers has ranked the Panama Canal one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.[2]

Environmental and ecological consequences[edit]

In 1978, it was published that "clearing the forest in the watershed might kill the canal".[156] In 1985, the forested portion had dropped to 30%.[157] As of 2000, deforestation through growth of human population, land degradation, erosion, and overhunting continued to be threats to the ecosystem of the Panama canal watershed.[156] Deforestation causes erosion, raising the bottom of the Gatun and Alajuala lakes lowering their water holding capacity.[157] Ship traffic routinely contaminates the water; in 1986, a crude oil spill east of the Caribbean entrance to the Panama Canal killed plants and invertebrates.[158]

Especially with the 2016 expansion, invasive species can travel faster, either on the hulls of ships or in ballast water.[159] Lake water has become salty over time.[157]

Master Key to Panama Canal and Honorary Pilots[edit]

During the last one hundred years, the Panama Canal Authority has granted membership in the "Esteemed Order of Bearers of the Master Key of the Panama Canal" and appointed a few "Honorary Lead Pilots" to employees, captains and dignitaries.[176] One of the most recent was U.S. Federal Maritime Commissioner Louis Sola, who was awarded for his work for supporting seafarers during the COVID-19 pandemic and previously transiting the canal more than 100 times.[177] Another recent award was to Commodore Ronald Warwick,[178] a former Master of the Cunard Liners Queen Elizabeth 2 and RMS Queen Mary 2, who has traversed the Canal more than 50 times, and Senior Captain Raffaele Minotauro, an Unlimited Oceangoing Shipmaster Senior Grade, of the former Italian governmental navigation company known as the "Italian Line".[179]