Perpendicular Gothic

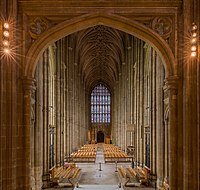

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-centred arches, straight vertical and horizontal lines in the tracery, and regular arch-topped rectangular panelling.[1][2] Perpendicular was the prevailing style of Late Gothic architecture in England from the 14th century to the 17th century.[1][2] Perpendicular was unique to the country: no equivalent arose in Continental Europe or elsewhere in the British Isles.[1] Of all the Gothic architectural styles, Perpendicular was the first to experience a second wave of popularity from the 18th century on in Gothic Revival architecture.[1]

The pointed arches used in Perpendicular were often four-centred arches, allowing them to be rather wider and flatter than in other Gothic styles.[1] Perpendicular tracery is characterized by mullions that rise vertically as far as the soffit of the window, with horizontal transoms frequently decorated with miniature crenellations.[1] Blind panels covering the walls continued the strong straight lines of verticals and horizontals established by the tracery. Together with flattened arches and roofs, crenellations, hood mouldings, lierne vaulting, and fan vaulting were the typical stylistic features.[1]

The first Perpendicular style building was designed in c. 1332 by William de Ramsey: a chapter house for Old St Paul's Cathedral, the cathedral of the bishop of London.[1] The chancel of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1337–1357) and its latter 14th-century cloisters are early examples.[1] Four-centred arches were often used, and lierne vaults seen in early buildings were developed into fan vaults, first at the latter 14th-century chapter house of Hereford Cathedral (demolished 1769) and cloisters at Gloucester, and then at Reginald Ely's King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446–1461) and the brothers William and Robert Vertue's Henry VII Chapel (c. 1503–1512) at Westminster Abbey.[1][3][4]

The architect and art historian Thomas Rickman's Attempt to Discriminate the Style of Architecture in England, first published in 1812, divided Gothic architecture in the British Isles into three stylistic periods.[5] The third and final style – Perpendicular – Rickman characterised as mostly belonging to buildings built from the reign of Richard II (r. 1377–1399) to that of Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547).[5] From the 15th century, under the House of Tudor, the prevailing Perpendicular style is commonly known as Tudor architecture, being ultimately succeeded by Elizabethan architecture and Renaissance architecture under Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603).[6] Rickman had excluded from his scheme most new buildings after Henry VIII's reign, calling the style of "additions and rebuilding" in the later 16th and earlier 17th centuries "often much debased".[5]

Perpendicular followed the Decorated Gothic (or Second Pointed) style and preceded the arrival of Renaissance elements in Tudor and Elizabethan architecture.[7] As a Late Gothic style contemporary with Flamboyant in France and elsewhere in Europe, the heyday of Perpendicular is traditionally dated from 1377 until 1547, or from the beginning of the reign of Richard II to the beginning the reign of Edward VI.[8] Though the style rarely appeared on the European continent, it was dominant in England until the mid-16th century.[9]